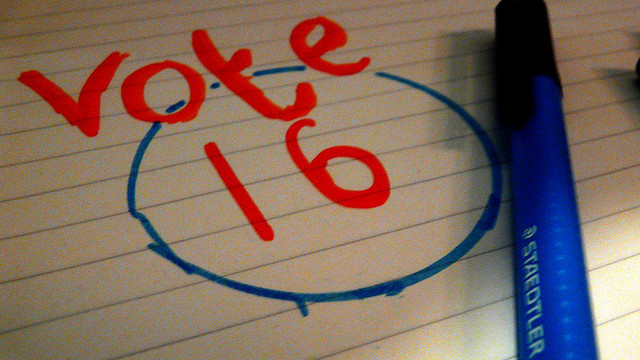

The Vote at 16 in 2016: Three things campaigners must do now

Hopes that 16 and 17-year olds might be allowed to vote in the EU referendum were quickly quashed by the government at the end of 2015. Benjamin Bowman considers where those pushing for the extension of suffrage should go from here. He argues that campaigners need to refocus on the core issues in the new year and emphasise that extending the franchise is not just about voting, but about reversing the trend of young people’s marginalisation and making sure that government benefits from the legitimacy and oversight of all its citizens.

The last hope for the Vote at 16 in the UK under the current Government was that, by clever politicking and with the support of the House of Lords, the franchise would be extended for the Referendum on EU membership planned before 2017. This seemed a desperate hope and, as many observers predicted, the Government stood its ground, calling the move in the Lords an inappropriate attempt “to change the nation’s electoral franchise through the back door”. In the words of John Penrose, Conservative MP for Weston-super-Mare:

“The House of Commons has voted on three occasions in recent months against dropping the voting age from 18 – including overturning a Lords amendment just yesterday. The government will re-affirm this clear position when the bill returns to the elected chamber and will seek to overturn this latest amendment from the Lords.”

Where can campaigners for the extension of suffrage to 16 and 17-year-olds go from here? The problem with the campaign for the Vote at 16 is that it has missed the wood for the trees. We are living in a time of deep young political, social and economic marginalisation, when young people face the worst prospects of any generation since the Second World War: yet, campaigns for extending the Vote have usually failed to address these core issues.

Smoking and voting are not the same

The usual appeal for the Vote at 16 goes something like this: teenagers are subject to the Government’s laws, they can smoke, work, and they are recruited by the military, so why can’t they vote? In my experience, campaigners frequently consider this a common sense argument.

It is not. It will convince no one who considers teenagers unready to vote, especially those who perceive youth as a period of apprentice citizenship: a time when children are gradually socialised to independence and personal responsibility. Neither does the argument really get to the point of what voting is about. Voting is different to smoking. It is right that we don’t require voters to pay tax, to be in work, or to have basic training with an automatic rifle, in order to take to the ballot box.

Remember: voting is about democracy

Elections are about giving people power. Votes need to give the electorate power over policy. In the UK, this is usually provided through representation in bodies like local councils and Parliament; it is occasionally provided by local or national referenda. Elections are the cornerstone of our Democracy. They underpin the legitimacy of our entire system of government from the dates of your neighbourhood bin collection to the renewal or otherwise of Trident. Votes are intended to provide for a representative body that truly represents their constitutents. Votes are also intended to render those in power accountable to those they represent in an effective machinery of Government by the people and for the people.

The question campaigners for the Vote at 16 should be asking is where 16 and 17-year-olds fit into that system of legitimate and effective governance. Firstly, 16 is the age at which young citizens are no longer bound to attending school, and can live independently. It is the age at which people can start working adult jobs like waitressing and factory work. In short, 16 and 17-year-olds are subject to Government policies without the provision for oversight or accountability. It is not enough for a vote to give someone a voice. It must give us power.

16 makes sense

Campaigners should feel confident arguing in favour for the ability of 16 and 17-year-olds to take on the Vote with knowledge, responsibility and – quite remarkably for those of us who expect young people to think in new or different ways from older generations – in a similar way to other members of the population. There are now working examples of the Vote at 16 elsewhere in Europe, including in national elections in Austria and in the independence referendum in Scotland. Vote at 16 campaigns should call far more than they do on the successes of practical experience. There are strong arguments that given young people’s marginalization from national politics, it is more practical to start with the Vote at 16 in local elections. Campaigners would do well to address the value of young voters to their local areas, where they are more able to act and where they may feel (or where we may hope they will feel) a stronger stake in the society around them.

It is also true that 16 makes more mathematical sense than 18. The age of full adult citizenship is 21, at which – for example – a worker is entitled to the full minimum wage. Yet, if you turn 18 on the year of a General Election, you will not be given your right to suffrage until you are 23. Restricting the vote to 18, then, excludes a great many adults from their right to oversight and accountability through elections through the simple mathematics of our five-year electoral cycle. We know from experience that people are ready to vote at 16, and in doing so, we guarantee everyone will have had a say over their Government by 21.

Where should campaigners go now?

Campaigners for the Vote at 16 were looking forward to 2016. Most expected a Labour government, a Lab-Lib or Lab-SNP coalition government, or a complex mixture of third parties led by Ed Miliband. Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the SNP had all pledged their support for the Vote at 16. The extension of suffrage had already had a trial run in the 2015 Referendum on Scottish Independence. In the end, though, an outright Conservative victory in 2015’s General Election sank campaigners’ hopes for the Vote at 16 to be in place for this year’s election of the Mayor of London and for local elections in England.

Cynics would say now is the time for the Vote at 16 to hibernate until Labour get in again. That would be a poor decision for one simple reason. The Vote at 16 is about more than just extending the franchise. It is about reversing the trend of young people’s marginalization on the one hand, and making sure that government at all levels benefits from the legitimacy and oversight of all its citizens, including the young, on the other.

I see the greatest value, and the best prospects, for the Vote at 16 if it can reorient our discussion of young citizens away from simply hoping they turn up at the ballot box, to including young people in the UK’s vital discussion about electoral reform. There are many questions on the table: does Government serve our needs? Does a vote really matter? How should the House of Lords be constituted? What should we do about low voter turnout? Is too much power concentrated in London? In all these cases, the Vote at 16 has an important role to play as a discussion of what democracy is about: not putting crosses in a ballot box, but about giving power to voters and legitimacy to their representatives.

—

Note: this post originally appeared on the PSA Insight blog. It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Benjamin Bowman is a Teaching Fellow in Comparative Politics at the University of Bath. He tweets @bennosaurus.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

#Votesat16 in 2016: Three things campaigners must do now https://t.co/AWbQL5R17Z

The Vote at 16 in 2016: Three things campaigners must do now https://t.co/bwuML6gZbk #ukpolitics #cdnpoli

The Vote at 16 in 2016: Three things campaigners must do now https://t.co/pfA78Mlaan

The Vote at 16 in 2016: Three things campaigners must do now https://t.co/21b86M7m70

#UK: A look at #campaigns to lower voting age & #youth participation in parties & politics. https://t.co/4GSHDE3SfN https://t.co/5ehmMvmK8D

The Vote at 16 in 2016: Three things campaigners must do now https://t.co/3Hrqt5Hajh

The Vote at 16 in 2016: Three things campaigners must do now: https://t.co/IEjc1Tlkgv

The Vote at 16 in 2016: Three things campaigners must do now https://t.co/kvQev8Snt4 https://t.co/VGwvDLMlsC

@democraticaudit how would you propose we educate 16 year olds about the political process and societal issues?