The Tax Credits dispute illustrates both the need for Lords reform, and why it is unlikely to happen any time soon

The Government is currently in conflict with the House of Lords over reform of Tax Credits, with at one point the possibility of a Lords ‘shutdown’ being inflicted by the Government. Stephen Barber argues that the conflict shows precisely why the Lords needs reform, but also shows why it is unlikely to happen any time soon.

Credit: Jimmy Baikovicius, CC BY SA 2.0

The policy might be government plans to scrap Tax Credits but the latest issue has become the authority of the House of Lords which has threatened to block government legislation. But while Cameron’s administration seems to have fallen out with the Upper House, don’t expect constitutional reform back on the agenda.

The frustrations are very real and the force of feeling on parts of the government benches was articulated by Tory MP Jacob Rees Mogg at prime minister’s questions this week:

‘Does he share my concern that if the other place were to vote against working tax credits this would be a serious challenge to the privilege of this House; a privilege codified as long ago as 1678? Does he further share my concern that this would entitle him to review the decisions of Grey and Asquith in relation to more peers to ensure the government can get its financial business through’

In reply David Cameron pointed out that under the 1911 Parliament Act, finance Bills are ‘decided in this house.’ Whatever the convention, the practical problem for the government is that it has no majority in the Upper House and there seems to be a determined cross-party coalition intent on damaging the legislation. In response, the prime minister is now seriously threatening to suspend the Lords or even flood it with new Conservative peers to swell the ranks of this already bloated and over-manned chamber.

Rees Mogg was referring to (obsolete) resolutions in 1671 and 1678 providing for pre-eminence of the Commons over financial matters. Cameron is also right in that the Upper House lost the power to block financial legislation in 1911 following the battle over Lloyd George’s 1909 Budget. He neglected to point out, however, that democratic reform has been promised ever since. But while the nature and composition of the Lords has changed from an hereditary chamber to one almost wholly appointed, the democratic will of the people has always found resistance.

In this sense it is rather intriguing that so many politicians in favour of abolishing Tax Credits are now highlighting the unelected nature of the Lords as a reason for peers not to frustrate the will of the Commons. They have a point of course. Although absent from the Conservative manifesto, the policy is the stated aim of a majority government recently elected at a general election (albeit on just 37% of the vote) and on which the Commons has voted (twice) in favour. While the nuance of the argument centres on the extent to which this is a money Bill, the heart of the case must be that if it is wrong in principle for an unelected House to block the elected Commons on Tax Credits, it is surely wrong to vote down any legislation.

It would be easy to point out (and so I will) that it was Cameron and his party who, in the last Parliament, ensured Lords reform failed. Whatever the weaknesses of the proposals championed by Nick Clegg in coalition, the direction of travel was to democratically legitimise the Upper House a full century after it was promised.

But don’t think this breakdown in relations means a great constitutional rush on the government benches to reform. The tone of the PM’s threat is that he wants to emasculate the Lords not legitimise it and it’s not hard to see why.

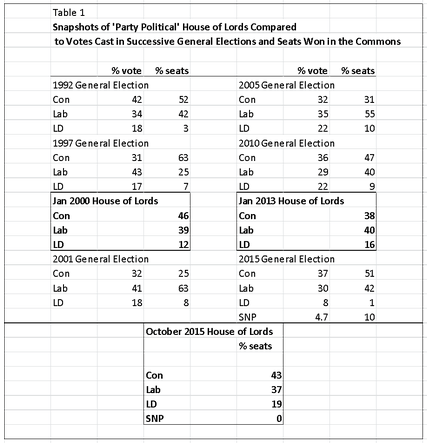

Despite lacking democratic legitimacy, the composition of the Lords better reflects voting intentions of electorate than House of Commons. If one considers the ‘Party Political House’ that is excluding Crossbenchers and Bishops, and takes into account the lagging nature of the Lords (new positions and party political strength are dependent on a prime minister post-election), the House of Lords composition is closer to votes cast at a general election than the Commons and has been since hereditary peers were (almost all) turfed out in 1999. Since the SNP is unrepresented in the Upper House, all three traditional Westminster parties actually do better than their vote in the 2015 Lords (as Table 1 highlights) though the governing party is still short of a majority.

Few would argue that, in the event of democratisation, the Lords should share the disproportional electoral system of the Commons. So were May’s election to be a guide, this would mean that two thirds of elected members would not take the governing party whip, extending further potential opposition. So an elected House would likely reject the will of government and do so legitimately. And it is perhaps this insight that gives many unelected peers the confidence to defy government on Tax Credits.

In a very real sense it is a shame because this showdown illustrates both the need for reform of the Lords and why it is unlikely to be on the government’s agenda any time soon.

—

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Dr Stephen Barber is Reader in Public Policy at London South Bank University. Find him on Twitter at @StephenBarberUK.

Dr Stephen Barber is Reader in Public Policy at London South Bank University. Find him on Twitter at @StephenBarberUK.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

What does the #taxcredits row tell us about the prospects of House of Lords reform? @StephenBarberUK discusses https://t.co/7DrZwLxGeQ

[…] real challenge thrown up by the row is what Democratic Audit highlights here, a proper reform of the Lords, but that impulse has been overwhelmed by events many times in the […]

My article on #HouseofLords and #taxcredits just published @democraticaudit https://t.co/ZACtM4vJtJ Enjoy.

The #TaxCredits row illustrates both need for #Lordsreform & why it’s unlikely to happen, writes @StephenBarberUK https://t.co/W65Yhc80Tm

The Tax Credits dispute illustrates both the need for Lords reform, and why it is unlikely to happen any time soon https://t.co/PQOC3BARaH

The Tax Credits dispute illustrates both the need for Lords reform, and why it is unlikely to happen any time soon https://t.co/rnbrtdWhU0

The Parliament Act 1911 was introduced to force through Lloyd George’s Peoples’ Budget to tax the rich and help the less well off. This row is about the reverse.

What goes around comes around?

The Tax Credits dispute illustrates both the need for Lords reform, and why it is unlikely to happen any time soon https://t.co/RPh36ZjlhX

Privilege to House of Commons codified 1678 over House of Lords to financial matters https://t.co/P1daEAFz8z https://t.co/VlI152nmTn

The Tax Credits dispute illustrates both the need for Lords reform, and why it is unlikely to happen any time soon https://t.co/lkxJNvQivk

The Tax Credits dispute illustrates both the need for Lords reform, and why it is unlikely to happen any time soon https://t.co/ew8lxoBQmt

The Tax Credits dispute illustrates both the need for Lords reform, and why it is unlikely… https://t.co/tOMb8qHGuN https://t.co/IzGUwWIjsx