Evidence from Belgium shows that gender quotas do not necessarily eliminate voter bias against women candidates

To what extent do electoral gender quotas change voters’ preference for male or female political candidates? Silvia Erzeel and Didier Caluwaerts examine the electoral evidence from Belgium, a country that has progressively adopted gender quota laws since the mid-1990s. They show that although the largest group of Belgian voters now vote for both male and female candidates there is still a voter bias in favour of male candidates. In particular they find that men and voters low in political sophistication still have a higher propensity to vote for men only.

Both in the UK and other European countries, debates about women’s underrepresentation in politics often concentrate on the necessity and effectiveness of quota rules. The central argument is that gender quotas overcome existing gender-based thresholds. They push parties to commit to fielding female candidates, thereby increasing their visibility and chances of getting elected.

What this argument overlooks, however, is that it is not enough to have women running as candidates, voters also need incentives to vote for those female candidates. A considerable amount of scholarship has paid attention to voters’ preference for male or female candidates, and one of the central mechanisms is the ‘gender affinity’ effect. Gender affinity assumes that voters will prefer candidates of their own gender, and especially female voters are expected to vote for female candidates, because they self-identify with women based on shared life experiences. In order for the gender affinity effect to lead to a more gender-balanced representation in politics, however, we need a balanced representation of both men and women as candidates, so voter will find at least one (wo)man that matches their own ideological or social profile. If this condition is met, male and female candidates are expected to have equal chances of getting elected. And gender quotas are considered a good way of ensuring this gender balance among candidates.

Belgium has strictly enforced quota laws. The current parity law requires 50 per cent of the candidates on all party lists for all government levels to be women, and at least one of the top two candidates has to be a woman as well. There is thus a perfectly balanced gender ratio among political candidates. Moreover, in Belgium, voters can cast preferential votes for multiple candidates on one party list. This system of multiple preferential voting, in combination with a high supply of female candidates as a result of the use of gender quotas, has created a window of opportunity for Belgian voters to cast preferential votes in a gender-balanced way, allowing them to support female candidates without turning down male candidates. As a result, our study of the Belgian regional elections shows that 45 per cent of all voters choose to support both male and female candidates. Voting for candidates of both sexes has become the default option.

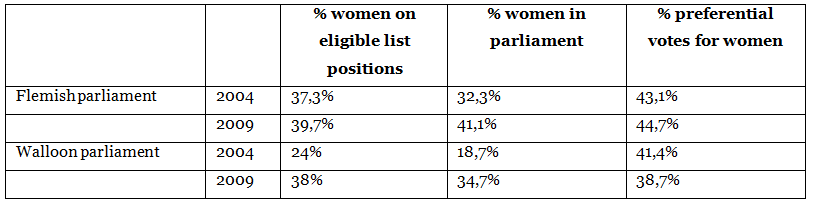

At the same time, however, there is need for caution as well. Female candidates still receive a smaller proportion of preferential votes than men (see Table 1). Sometimes this has been attributed to a party bias: parties are less likely to put women at the very top of their list, and as a result women receive less media exposure, less public visibility and less financial means to target voters. But even when quotas are in play, the voter bias against female candidates might be more robust than expected.

Table 1: Percentage of women in Belgian regional politics

Data from the Institute for the Equality of Women and Men.

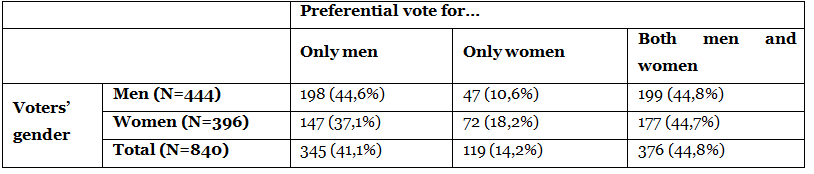

Our study for instance showed that female candidates are still at a disadvantage when we look at those voters who do express a clear preference for the gender of the candidate. As shown in Table 2, 41 per cent of the voters still cast a vote for men only, whereas 14 per cent of the voters do so for women only. The idea that there is a strong experiential bond between female voters and female candidates is moreover a misconception. After control for confounding variables, our results suggest that the link between voters’ gender and candidates’ gender exists primarily among men. In other words, men have a higher propensity to vote only for men, and women do not necessarily vote only for women. This is a striking finding, one that mirrors recent findings in Finland.

Table 2 : Preferential voting for only men, for only women or for both men and women, by voters’ gender

Note: analysis based on the PARTIREP Regional Election study

In addition, our study finds that voters’ political resources play a significant role, even more so than voters’ own gender identity. Those voters who support only male candidates are generally less politically interested, less politically knowledgeable, less politically informed, and less politically trusting. In other words, whereas voting for men and women alike has become the default option in Belgium, voters with less political sophistication still show a higher propensity to vote only for men.

In conclusion, a voter bias in favour of male candidates still exists in Belgium, and gender quotas, despite leading to a more balanced gender representation in parliament, have not (entirely) eliminated this bias. This presents a serious challenge for policy makers, especially because the voter bias exists among a group of uninformed and uninterested voters. Even if parties and media give more visibility to female candidates, they are preaching to the converted: they may only reach the group of voters who is already sensitive to the issue and already votes for women. Despite the introduction of gender quotas, some groups in society seem particularly inert in their ideas about gender equality, but even though full gender equality in politics is hard to come by, it remains too valuable not to pursue.

—

Note: This article summarizes findings from the authors’ recent paper in Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. Data used in this study were gathered within the PARTIREP consortium. It represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Silvia Erzeel is a postdoctoral researcher of the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (F.R.S.-FNRS) at the Institut de Sciences Politiques Louvain-Europe (ISPOLE) of the Université catholique de Louvain. Her research focuses on comparative politics, party politics, political representation and diversity issues.

Silvia Erzeel is a postdoctoral researcher of the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (F.R.S.-FNRS) at the Institut de Sciences Politiques Louvain-Europe (ISPOLE) of the Université catholique de Louvain. Her research focuses on comparative politics, party politics, political representation and diversity issues.

Didier Caluwaerts is a postdoctoral researcher of the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO) and an Assistant Professor of Public Policy at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel. His research focuses on democratic and social innovation, with a particular focus on deliberative democracy.

Didier Caluwaerts is a postdoctoral researcher of the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO) and an Assistant Professor of Public Policy at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel. His research focuses on democratic and social innovation, with a particular focus on deliberative democracy.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Belgium shows gender quotas do not necessarily eliminate voter bias against women candidates : Democratic Audit https://t.co/ZpGE0fqjUh

Quotas don’t eliminate voter bias against female candidates. still lead to equal representation https://t.co/vvAqBp54yj @rep__2020 @PippaN15

RT @democraticaudit: Evidence from Belgium shows that gender quotas do not necessarily eliminate voter bias against women candidates http:/…

Evidence from Belgium shows that gender quotas do not necessarily eliminate voter bias against women candidates https://t.co/CFRWNHWRN7

Evidence from Belgium shows that gender quotas do not necessarily eliminate … – Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/ty1zDaADl6 #Belgium #News

Evidence from Belgium shows that gender quotas do not necessarily eliminate voter bias against women candidates https://t.co/Cex5g4aQAk #O…

‘Evidence from Belgium shows that gender quotas do not necessarily eliminate voter bias against women candidates’. https://t.co/nBquHi6rWk

Evidence from Belgium shows that gender quotas do not necessarily eliminate voter bias… https://t.co/ct9xLeFmVh https://t.co/iNzMtv60ud