Online communities and the law: how e-participation is changing voting rights

Can digital democracy facilitate the creation of a new, computer-oriented direct democracy? Silvia De Conca argues that some kind of of hybrid system might represent the best way of creating such a system, and that new tools such as LiquidFeedback.org are providing a practical example of how to marry the two approaches.

Credit: Centre for E-Government, CC BY NC SA 2.0

It is now common to say that the Internet has changed our lives, for good or ill. Although it might not appear at a first sight, public law is one of the fields affected by the Internet, including voting rights. The modalities of how the Internet influences the law have not been defined yet, but Gunther Teubner and the Social System Theory help shedding a light on the mechanisms and effects of such changes.

The Social System Theory has demonstrated how network relationships stimulate diffused and asymmetrical interactions that, in turn, exercise pressure on the existing social system in order to obtain a change. Such pressure leads, therefore, to new balances, new sets of standards where legal and non-legal elements coexist: the so-called civil constitutions. Civil constitutions modify the existing law, creating new rights that are defined by Teubner as “hybrid” since they contain elements belonging to different spheres of the law, as well as elements deriving from non-legal dimensions. The process through which legal and non-legal elements synthetize together to create a hybrid balance is called by Krippendorf “morphogenesis”.

Voting rights are currently the object of a morphogenesis process deriving from networks (the so called “communities”) born and living on the Internet.

Online communities, acting as networks, are gradually challenging parliamentary and representative democracy. Even if it is highly unlikely that the representative democratic system will be replaced by perfect direct democracy, the communities operating on the Internet, by discussing changes to the constitutional paradigm, are exercising pressure to include elements of direct democracy.

Online communities often use forums, platforms and softwares to carry out the democratic discourse. An example of a platform gravitating around collective and direct democracy is the LiquidFeedback project.

Based on the concept of collective policy drafting, LiquidFeedback is an open-source software for proposition development and decision making. It combines the use of online rating of proposals through the issue of feedbacks and rankings, and the concept of “liquid” democracy, i.e. the possibility to delegate voting rights.

LiquidFeedback is characterised by the following elements:

- possibility of proxy voting (delegation and sub-delegation of all or part of the vote)

- publicity of the votes and transparency of the decisions

- a decision making mechanism implemented by means of the Schulze mathematical method (which does not provide for a yes/no decision, but for a ranking of choices)

The principles informing the project, namely those of direct participation into the democratic life, collective policy making and promotion of an alternative to the parliamentary representation are meta-legal concepts embedded in the LiquidFeedback project. An important role in this sense is also played by the mathematical rules and methods used by the software, which reflect values and standards not belonging to the legal sphere, but deeply influencing it, especially with regard to the legitimacy and reliability of the voting quorum.

The above circumstance represents the evidence of the hybrid nature of LiquidFeedback, but a more convincing confirmation can be found in the factual characteristics of the software itself. The system created shows, in fact, a dense integration of elements belonging to private law together with elements typical of fundamental rights and public law.

In this regard, the possibility of transitive, topic related proxy voting catches the attention. A provision belonging to corporate law is, here, modified and adapted to be introduced into public law and serve the cause of civil rights.

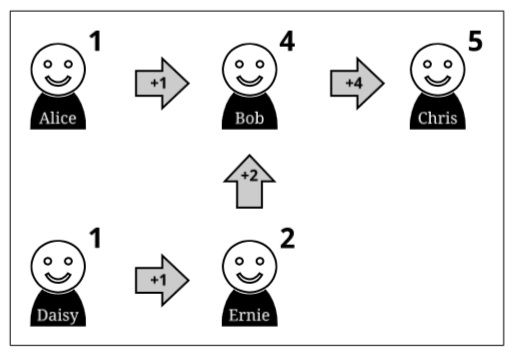

Figure 1: the mechanism of transfer of voting weight

The introduction of a mechanism of transfer of voting weight reflects a revolutionary change of semantics in the field of civil and political rights. It introduces concepts connected to business and market into the sphere of constitutional law, without, however, bending this latter to market reasons, but creating a new level of integration of both elements, in a real morphogenesis process. Proxy voting, in the view of the developers of LiquidFeedback, allows each individual to express their vote on the topics falling within their personal expertise, and delegate to more expert subjects the vote on other topics, in a fashion that recalls the concepts of open source and collective intelligence already in use with regard to the Internet, but that are not commonly associated to traditional democratic systems. It must be noted, hoewever, that the voter delegates the expression of the preference to another subject without any voting instructions. This represents a waiver to any possible form of control over the appointed agent, and leaves doubts concerning the responsibility regime to apply to agents.

LiquidFeedback presents other particular features connected to the voting mechanism, features that mark a further detachment from the traditional elements composing voting rights. The open ballot is indeed one of those. One of the fundamental provisions in most democratic systems is the anonimity of cast votes, which protects both the voters and the entire system from distortions, such as blackmailing or the sale of votes in return of favours or money. The creators of LiquidFeedback, however, see in anonymity an increase of the risk of cheating during voting procedures, and have decided to promote open ballot and transparency. It must, however, be noted that the developers fail to address the problem of the protection of the legality of the voting itself against the above mentioned distortions, which should be taken into consideration in every possible decision making process and at every regulatory level.

Finally, another difference between the traditional voting right and the voting right featured by LiquidFeedback is given by the circumstance that voters do not vote in favour of one option and contrary to another. The use of mathematical methods and theories, and in particular of the Schulze method, allows voters, instead of expressing a yes-or-no option, to create a ranking of preferences. The alternatives put to vote are ranked by the users from the most favourable to the most adversed. The winning alternative is, therefore, not the one that obtains more “yes”, but the one that is ranked as the most favoured and, at the same time, as the less adversed. This form of ponderation is absolutely new to representative democracy, which is based on the majority principle, but appears similar to the rules followed by public administrations during the evaluation of bids in public tenders. Once again, the elements constituting the traditional democratic system and the voting right are challenged by the new features introduced by LiquidFeedback.

It is plausible to affirm that LiquidFeedback represents an example of civil constitution as theorised by Gunther Teubner, and presents a hybrid nature. The pressure exercised by the network at the basis of the LiquidFeedback project can affect the content of the voting right, introducing elements that do not fall among those traditionally composing the voting rights but are borrowed from other spheres.

As already mentioned, representative democracy is unlikely to be put aside by direct democracy. Nevertheless, if combined together, both the traditional and the new balances can give life in time to a new and more elaborated system of public law, as a result of a morphogenesis process.

The creative strength of morphogenesis processes can have, however, a disruptive effect. Despite Teubner’s belief that the morphogenesis process creates an additional level of reality in which all the elements are synthetized, the introduction of hybrid elements into existing rights might lead to losses and trade-offs, as in the case of the sacrifice of anonymity in favour of open ballot. A new balance of fundamental principles can, consequently, derive from the rise of civil constitutions, and elements of the previous system might inevitably go lost.

Whether the new balance is preferred by the civil society shall, however, not be given for granted, and can only be fully assessed during more advanced stages of the process.

Finally, it shall be noted that the circumstance that the morphogenesis process consists of an often slow and long work in progress can lead to temporarily inconsistent governance systems, and can affect negatively individual rights. In relation to that, the interactions between new civil constitutions and the traditional state-centred ones (and vice-versa) acquire a prominent importance, shifting, once again, the perspective on the basic principles of the law.

A hybridisation between representative systems and direct democracy can lead to a huge step forward for a democratic country. In order to foster a higher degree of direct participation of citizens to the democratic process it is fundamental to limit counter effects. For this reason, it is important to carefully observe and analyse its implications at many different legal and social levels, to be able to enhance positive changes and limit possible undesired consequences.

—

Note: This post represents the views of the authors, and does not give the position of Democratic Audit or the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting.

—

Silvia De Conca is a Professor in the Department of Law of the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education, Chihuahua, Mexico silvia.deconca@gmail.com. She is alumni of the LSE.

Silvia De Conca is a Professor in the Department of Law of the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education, Chihuahua, Mexico silvia.deconca@gmail.com. She is alumni of the LSE.

![]() This post is based on a presentation given by the author at the 2015 CeDem conference in Krems, Austria.

This post is based on a presentation given by the author at the 2015 CeDem conference in Krems, Austria.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

LSE alum Silvia De Conca writes for @democraticaudit on how e-participation is changing #voting rights https://t.co/OGGTCQVhk2

Online communities and the law: how e-participation is changing voting rights @silviapetulente https://t.co/LatD4LSRuf

Online communities & the law: how e-participation is changing voting rights https://t.co/KZUV7uSOVl

Online communities and the law: how e-participation is changing voting rights https://t.co/gGRpAeMcuu

Online communities and the law: how e-participation is changing voting rights – Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/ZDXaC5RmX1

Online communities and the law: how e-participation is changing voting rights: Can digital democracy facilitat… https://t.co/VAJaUUQQBc

Online communities and the law: how e-participation is changing voting rights https://t.co/Xs2mXHYMKF #Option2Spoil

Online communities and the law: how e-participation is changing voting rights https://t.co/6lIzS9WYMK https://t.co/KwUDDUgKGa