The First-Past-the-Post electoral system is breaking up the UK

The First Past The Post electoral system exacerbates divisions between the different parts of Britain, adding to pressures that could break the union, with Thursday’s General Election potentially hastening this process. Tim Oliver discusses whether it is too late to change course.

Credit: Steve and Clare, CC BY NC 2.0

The list of problems with the First Past The Post (FPTP) electoral system is a long and familiar one. It produces a House of Commons that fails miserably to represent accurately the political outlook of the British people.

The 2015 election looks set to deliver yet another questionable result, putting to an end ideas the 2011 referendum on the Alternative Vote killed off electoral reform. This time – whether it is the result in Scotland or across England – the focus will be on how FPTP makes Great Britain* appear more politically divided than it actually is.

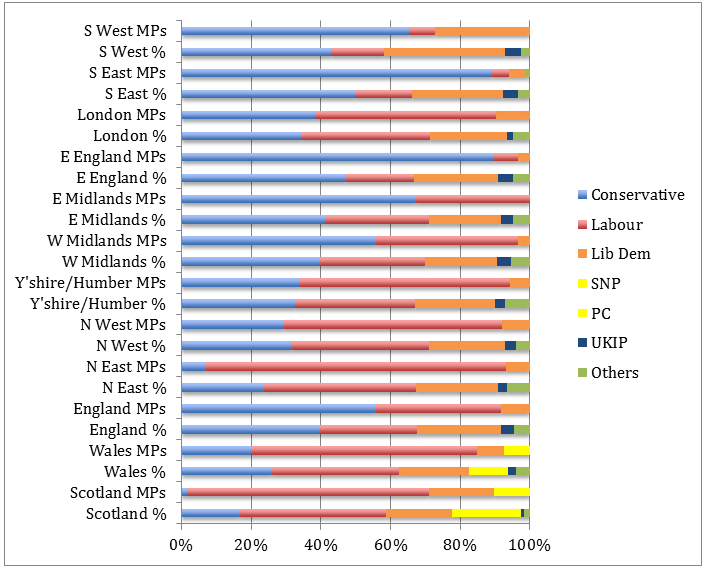

There will always be political differences between the different nations and regions of Britain. But FPTP produces high levels of disproportionality in how votes are reflected in parliamentary seats. As the table below shows, in the 2010 general election FPTP exaggerated the political differences between Britain’s regions and nations. The result made it appear as if Labour or the Conservatives dominated certain areas despite neither party securing more than 50% of the votes in any part of Great Britain.

FPTP therefore makes Britain appear more politically divided than it actually is, playing to the agendas of nationalists, creating exaggerated senses of division and leaving Labour and the Conservatives as parties that are no longer truly national parties. Instead the two parties ignore vast swathes of the country where their representation is small even if in those areas they secure a sizeable proportion of votes cast.

The work of the British Social Attitudes Survey has shown that differences between people in different areas of Britain are not always as pronounced as Britain’s political divisions might indicate. Clinging onto FPTP therefore risks reinforcing and accentuating divisions, straining the unity of the UK.

Scotland

A surge in support for the SNP in Scotland means that on somewhere between 45-50% of the vote the SNP could soon win almost all but a few of Scotland’s 59 MPs. The SNP’s victory will be one the party should relish given FPTP has penalised them in the past while awarding Labour the majority of Scottish seats despite Labour never securing a majority of Scotland’s votes. But the 2015 result will add to a sense the Scots are far removed from the rest of the UK’s political system.

FPTP has long produced questionable results in Scotland. In 1997 the Conservatives lost all their Scottish MPs despite securing 17.5% of the vote. Today their sole Scottish MP is often the butt of the joke that there are more giant pandas in Edinburgh zoo (Tian Tian and Yang Guang) than Tory MPs in Scotland. That in 2010 416,000 Scots (16.7%) voted Tory makes a mockery of the idea that Scotland is a ‘Tory free zone’.

Labour may soon be the butt of a similar joke. If current polls are right there could soon be more Buff-cheeked Gibbons in Edinburgh Zoo than Labour MPs in Scotland. This could be despite Labour securing more than a quarter (perhaps even a third) of the vote.

The SNP itself has long suffered under FPTP. Their previous peak of 30.4% support in October 1974 delivered them only 11 (15.5%) of Scotland’s seats. Their 19.9% of support in 2010 earned them 6 (10%) of the seats. The small number of seats it has won over the years has allowed the House of Commons and UK politics to underestimate growing nationalist support.

The SNP have long supported electoral reform, but could soon face an awkward choice. Winning around 50% of the votes on May 7th could see them take more than 75% of Scotland’s seats. If in the new parliament a change to a more proportional system of electing MPs became a possibility then SNP MPs could end up deciding the fate of a reform that would almost certainly see some of them lose their seats at a 2020 general election.

More than anything, the unfair results in Scotland have led to the West Lothian question being politicised. This is in no small part because the Conservatives with their one Scottish MP see little to lose from pushing it (although some Conservatives are weary, as are their potential coalition partner the Northern Ireland DUP). Labour might be tempted to take a similar approach if they can never win back a large number of Scottish seats.

Talk of ‘English votes for English laws’ ignores the plethora of research showing it is not so simple. Fairer representation that limits the potential for this to become a question of a Conservative England versus Labour/SNP Scotland would limit what for the UK could be a divisive and destructive debate about a complex problem.

England

This issue is not simply about Scotland. Even if Scotland were to leave the UK FPTP would continue to exacerbate a sense that England is deeply divided between a Labour north v’s Conservative south, of Lib Dems clinging on in the south west, or of London v’s everywhere else. The 2015 result looks set to leave us with no accurate representation of support for UKIP or the Greens, meaning they and their many voters will be ignored.

It has been a common enough complaint in the north of England that a Conservative party made up largely of MPs from the south has little if any interest in the needs of the north, and vice versa for southern views of a Labour party dominated by northern MPs.

It is easy to see why when in 2010 the Conservative party won 82% of the 197 seats in the south (excluding London) despite securing under half the votes in those regions. The resulting 163 Conservative MPs made up 53% of the Conservative party in the House of Commons. In comparison, their 42 MPs from the north (north west, north east, Yorkshire and the Humber) made up 27% of the 157 MPs from these areas, with them forming a mere 14% of Conservative MPs overall.

Meanwhile 40% of Labour’s 258 MPs came from the north west, north east and Yorkshire and the Humber, where they made up 66% of those regions MPs. Labour’s 12 MPs in the whole of the south (excluding London) made up a paltry 2% of the party’s MPs.

Efforts by either party to improve their performance in the north or south would be improved if they started with representation that more fairly reflected the higher levels of support they secure in these areas than FPTP gives them. In 2010 that would have given Labour roughly 14 MPs in the south east, not 4. The Conservatives would have seen their number of MPs in the North East rise from 2 to 7. These might seem small numbers, but if in 2010 this had been repeated across Britain then the distribution of Labour and Conservative MPs would not have been so uneven.

A more even distribution – and an improved possibility of securing seats in all areas – would also incentivise both parties to govern in the interests of all parts of Britain. With Labour MPs concentrated in an economically disadvantaged north, and Conservative MPs in the more dynamic and growing south, it is easy to see why Labour is tempted to squeeze the south for redistribution to the north while the Conservatives do the opposite.

London is the one part of southern England that stands out, having until 1997 largely mirrored the rest of British politics. This is not simply because in 2010 it elected more Labour MPs than Conservatives, despite Labour winning only a slightly larger share of the vote. It is because London is a place apart from the rest of the UK. Not only is it distinct as the home of the UK’s government and political elite, it also has an increasingly unique population, identity and economic needs.

Ignoring growing differences between the capital and the rest of the union will be made easier by FPTP limiting the success elsewhere in England of UKIP, a party which defines itself as anti-London because of the city’s liberal metropolitan values (although in London the party can secure a sizeable proportion of the vote, securing 16.9% of the vote in the 2014 European Parliament elections). Not having to panic in the face of a possible FPTP electoral wipe out would also help parties avoid the sort of debate seen in Labour’s Jim Murphy attempt to draw on London’s wealth to prop up Labour votes in Scotland.

Voting for the Union

British politics has reached a point where it is no longer in the interests of any party to maintain FPTP. They must look beyond outdated ideas of party interests to see that retaining FPTP is no longer in the interests of maintaining a United Kingdom.

If the Conservatives wish to see the union survive they need to back a more proportional electoral system to allow them to build support across the country. They will also need a system of PR if they are to have any hope in future of forming a coalition with parties such as the Liberal Democrats or UKIP, parties who would be in a stronger position to help under a more proportional electoral system. Labour will need electoral reform to rebuild their support in Scotland and to reach out beyond their northern heartlands. The SNP should not count on being on top forever in Scottish politics. For the Liberal Democrats, UKIP, Plaid Cymru, the Greens and others the case for reform is obvious.

This is, however, more than about political parties. It is about ensuring the House of Commons represents fairly the politics of the union it serves. Even if Scotland is headed irreversibly out of the union, it is not too late to learn from mistakes to ensure the rest of Britain can better manage its internal tensions. If we want a parliament and national government that continues to exaggerate divisions, that fails to respond to the full range of needs across the UK, then that is what we can expect FPTP to deliver.

Of course, the flaws in the UK’s constitutional setup and politics go beyond FPTP. Other reforms will be needed to help Britain manage its differences, whether in the form of proportional representation for local government, a more federal UK, an end to the silo mentality by which devolution has been developed and administered, or an elected House of Lords whose membership contains a territorial dimension.

Any constitutional convention or wider discussion that follows the 2015 election will inevitably look at the issue of electoral reform given the central part it plays in defining the UK’s national politics. No electoral system is perfect and all will struggle to accurately reflect the political diversity of modern Britain. But many systems of proportional representation are preferable to the current FPTP electoral system that is dividing rather than uniting the United Kingdom.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Dr Tim Oliver is a Dahrendorf Fellow at LSE IDEAS. His research focuses on UK politics, UK-EU relations and transatlantic relations. Educated at the University of Liverpool and the LSE, he has worked in the House of Lords, the European Parliament, the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Berlin), the SAIS Center for Transatlantic Relations, and the RAND Corporation (both in Washington D.C.). He has taught at LSE, UCL and the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.

Dr Tim Oliver is a Dahrendorf Fellow at LSE IDEAS. His research focuses on UK politics, UK-EU relations and transatlantic relations. Educated at the University of Liverpool and the LSE, he has worked in the House of Lords, the European Parliament, the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Berlin), the SAIS Center for Transatlantic Relations, and the RAND Corporation (both in Washington D.C.). He has taught at LSE, UCL and the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

@AleGuerani “First-Past-the-Post” è secolare,quindi è giusto e non deve essere criticato #LOL

https://t.co/0lgSiToLwa https://t.co/Vi8YjXdvjY

2/2 ‘#FPTP .. makes Britain appear more politically divided than it actually is, playing to agendas of nationalists’

https://t.co/AQVD43MVkS

FPTP is breaking up the UK by exacerbating regional differences: https://t.co/HoWAry8YHi

Yes: The First-Past-the-Post electoral system is breaking up the UK https://t.co/RujqKlmXpd

Also, a timely reminder the our electoral system is no longer fit for purpose: https://t.co/zyBc9NGUT6

The First-Past-the-Post electoral system is breaking up the UK via @lsepubaffairs https://t.co/3CgbZb0yFK

Time for change: “@democraticaudit: The First-Past-the-Post electoral system is breaking up the UK https://t.co/PQN0i7TnRj“

RT @Usherwood: The First-Past-the-Post electoral system is breaking up the UK https://t.co/UMg8FqtUN8 good piece

The First-Past-the-Post electoral system is breaking up the UK : Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/jTKMNLGd4r

FPTP is breaking up the UK. Interesting perspective given tomorrow’s likely result. https://t.co/gqfUNuCQAJ

RT @CJTerry: One of my two favourite academic Tim Olivers on how FPTP is breaking apart the UK: https://t.co/lk8unhMOBC

The First-Past-the-Post electoral system is breaking up the UK https://t.co/XjnjGXgU03

The First-Past-the-Post electoral system is breaking up the UK https://t.co/i2neyecoX4 #Option2Spoil

The First-Past-the-Post electoral system is breaking up the UK https://t.co/b4rACdhVBx

RT @PJDunleavy: The First-Past-the-Post electoral system is breaking up the UK https://t.co/tb7xIv8CJK cc @peplobera