Policymakers should be considering the impact on media plurality of digital intermediaries such as Facebook

To conclude with the LSE Media Policy Project’s Plurality Dialogue series, Damian Tambini addresses the most crucial questions that policymakers should be considering with regards to the role that digital intermediaries play in the democratic process.

BBC Media City in Salford (Credit: Camila Clarke, CC BY NC 2.0)

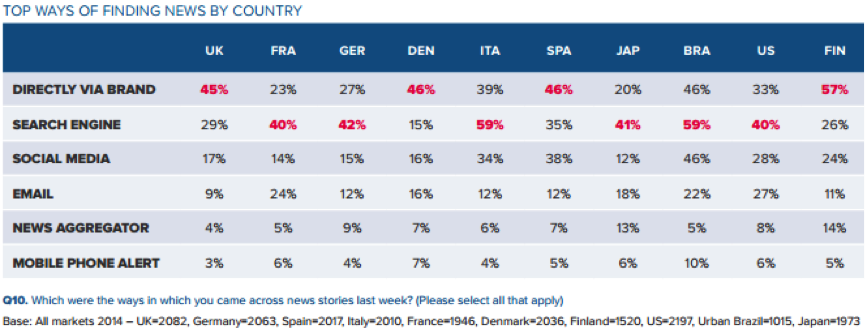

How might Facebook, Google and other intermediaries influence the outcome of the 2015 UK election? Are they displacing newspapers and TV as kingmakers? As Robin Foster noted, and data from the Oxford Reuters Institute illustrates, there is ample evidence that social media are rapidly rising as a source of news, posing deep questions about the automated, pseudo-editorial processes that increasingly determine the flow of news not only during elections but between them as well.

We will of course not get close to answering my question until after the election in May, and attempting to predict the behaviour of these private companies is in any case likely to end badly. The more urgent question arguably is what, if anything, should be done about the possibility that these global companies might influence such an outcome and might be emerging as power brokers in our democracies? As Robin Mansell intimates, it will take a long time to reach a workable consensus on the appropriate legal and ethical frameworks that will ensure that digital intermediaries do not undermine democratic legitimacy. The positions set out in this blog series have made a significant contribution to the emerging debate about those frameworks.

Points arising from our series

First, there is little evidence – aside from a few well-publicised episodes such as the Facebook voting experiment – that intermediaries are deliberately manipulating political communication. The mere hint of a possibility that news feeds may be manipulated tends to lead to immediate outrage: for example in the discussion about Facebook and the Ferguson riots. The reason the debate about algorithmic power is of critical interest to intermediaries is that they are at pains to show that they are neutral ‘dumb’ conduits with no editorial function, and that whatever potential power they may have they are not using it. Rather, they seek to demonstrate they are facilitating open plurality of news by allowing users to construct their own bottom-up editorial machines through ‘friending’, ‘liking’, past searches and a range of online behaviours.

A second point that arises therefore, is that whilst we don’t have much evidence of manipulation of democratic communication by digital intermediaries, there are principled and theoretical reasons to suspect that policy and regulatory attention will be focused on the nexus of news and intermediaries in the future. This is not only because other commercial competitors will find it is in their interest to focus on the power of the intermediaries, particularly after the failure of competition based investigations to fully address publishers’ complaints, but the role of intermediaries will also remain under the spotlight because history tells us that powerful industrial interests will use the power resources they have at their disposal – if not in the interests of owners, at the very least in the interest of the company.

Thirdly, it is possible that public interest concerns arise about intermediaries and media pluralism even if there is no attempt to manipulate opinion. This is the ‘Daily Me/ Filterbubble’ critique arising from the very nature of social media sharing. Here there appears to be conflicting evidence, and some real questions for policymakers. The notion – advanced by Natali Helberger, Ellen Goodman and Philip Napoli – of ‘diversity by design’ or a ‘serendipity engine’ would be one of the self-regulatory solutions that Mansell,Foster and others see as an appropriate outcome at this stage of market development. Intermediaries might however be reluctant to step into such a role however, as this would in itself undermine the claim to neutrality of their algorithms.

Fourthly, even the perception of a problem is bad for democracy. If intermediaries could manipulate public opinion, that is a problem in itself. Goodman points out that “we are taking the intermediaries’ word for the ‘benignity’ of the practices of these algorithms”. This is a big ask.

The challenge, as Foster pointed out, is to maintain a dialogue about these concerns, which will have implications for development not only of a theory of harm of use to regulators such as Ofcom who are currently consulting on this, but the development of an ethical language and self-regulatory code on what is acceptable, what is not, and what is to be praised in terms of design and practices of intermediary code.

What legal and ethical concepts should apply? Media plurality as a framework

When a new phenomenon arises, it is inevitable that it will be approached using regulatory concepts, tools and codes that applied to the old. Most regulatory concern with Google and other intermediaries in recent years has applied competition law concepts of market dominance and its abuse. In this blog series we have been examining whether the normative-legal concept of media pluralism (as we know it in Europe) or media diversity (in the US) is adequate to capture the problems that arise in relation to the new intermediaries.

What seems clear is that the concept of media pluralism is useful for grasping some of the concerns raised in relation to the digital intermediaries, but not all of them, and as the European Commission,DCMS, House of Lords and Ofcom as well as governments throughout Europe are finding, it is difficult in any case to come up with practical, applicable, justiciable measures and regulatory frameworks which would bring intermediaries within a plurality framework. Put simply, through the prism of media pluralism, it is easy for the intermediaries to sustain the claim that there is in fact not a problem, as Google’s post in this series and the company’s evidence to the recent House of Lords discussion make clear.

Claims that digital intermediaries are a current and immanent threat to ‘available and consumed’ diversity of news do indeed require some creative mental gymnastics on the part of the commentator, as Goodman and Napoli hint. Most of our bloggers are more content with arguing that there is theoretically a problem here, and that whilst it is not a huge issue right now, it is certainly possible to make out the shape of some potential problems in the future.

This is because the existing policy paradigm on media pluralism raises, but does not adequately grasp, issues with the role of new intermediaries. Whilst Google’s Peter Barron and Simon Morrison may be right that the new media environment as a whole makes available a huge plethora of news, and they may even be right that consumers on the whole are consuming a wider plurality of viewpoints, there are still dangers. Whole market plurality of offer and consumption reported through user surveys are only part of the problem. It is the combination of control of data and message targeting that is the key challenge, as Ellen Goodman and others underline.

Despite the sanguine approach of Google and Facebook, Goodman does outline some practical examples of the types of behaviour that could raise significant concerns from a traditional media plurality perspective. These concern neutrality of the network rather than intermediaries however. If a social network uses data to target news, campaigns or voting reminders, to particular groups of consumers, such as the Wikipedia/ SOPA campaign, or the Facebook voting experiment, the question here would rather be whether existing electoral law might apply, but outside of elections there are concerns about lobbying and campaigning power of Facebook. Campaigns on organ donation are one thing, but social networks, as Dave Eggers’ excellent novel The Circle points out, do have their own lobbying interests to promote too.

It would be worth asking whether, within the current legal and regulatory framework in Europe, these kinds of practices would fall foul of existing media plurality rules. The answer, currently, is that they might in some cases, where there is wide regulatory discretion to include online in assessments of media plurality. In practice, the machinery of monitoring of media plurality at both EU and member state level is increasingly focusing on these powerful shapers of news markets. More research is needed on how different European jurisdictions are responding and applying their existing regulation.

When Barron gave evidence to the Lords select committee on behalf of Google he went so far as to claim that ‘The framework behind the algorithm is to do with the stated principles of diversity and plurality.” The eternal question of public policy is whether competition can deal with the problem, or whether rules specific to this sector are necessary. The answer to that question will depend on whether intermediaries engage effectively in a genuine dialogue about options, ethics and self-regulation. This means being open about what they are doing, providing real transparency and collaborating with researchers.

Self-Regulation is part of the solution – but there is no consensus on ethics and transparency

In conclusion, there are two types of questions. A short-term practical question is whether the current framework on media plurality in any way ‘captures’ the new intermediaries. This need not detain us long, because in most cases legislative frameworks are based on reference to delivery media (such as the focus on TV in Germany). But where Ofcom is currently scratching its collective head is where it has a wide discretion to monitor media plurality (other regulators have similar duties).

But Ofcom, a creature of statute, will only do what is asked of it and this blog post series does establish that the plurality dialogue should not stop here. Several witnesses to the recent House of Lords Inquiry stated the need for an independent Commission on media power and plurality. This commission needs to be independent of both Parliament and Government, and the need for such an initiative – which would pick up the plurality concerns of Leveson, but bundle them with intermediary concerns, is greater than ever. Now, before the legal and ethical framework is set for the intermediaries, is the time for this kind of public debate. It is happening elsewhere in Europe and this policy area is one where Europe looks to the UK for sensible leadership.

We need a watching brief. The problem with algorithms is that they are opaque and little understood. This is not a good thing when it comes to the workings of democracy, elections and policy.

—

This article gives the views of the author, and does not represent the position of the Democratic Audit UK blog nor of the London School of Economics. It originally appeared on the LSE Media Policy Project blog, and is reposted with permission. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Damian Tambini is Senior Lecturer at the London School of Economics and an Associate Fellow at the Institute for Public Policy Research, and at the Oxford Internet Institute.

Damian Tambini is Senior Lecturer at the London School of Economics and an Associate Fellow at the Institute for Public Policy Research, and at the Oxford Internet Institute.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

We can see when logging into such sites as Facebook that our individual profile pages no longer contain only our information. If you look to the side, you can see the scrolling advertisements and the news stories that just so happen to correlate with things you, or someone utilizing your computer, may have browsed recently. For instance, I recently visited a website for a baby gift for a friend. A few days later, I noticed an advertisement for that same site on my profile. I’ve only ever looked at the site, never purchased anything, but somehow they know exactly where I’ve been and what advertisements may resemble my shopping habits.

I will say that I know this happens, but isn’t that the point of this blog? It is easy for any entity with an internet connection and money to be able to tap into our browsing history and see what ad campaigns might strike a chord with us. Then, they simply put it into our news feeds, or on our profiles, and we’re supposedly more apt to look at it.

I’ve recently been reading a book by Charles Ess called, “Digital Media Ethics” that details situations such as these as inherently unethical. He states, “..where it was once comparatively difficult to capture and transmit information that she or he might consider private, the advent of digital media, beginning with computer systems that can store and make easily accessible a wide range of information about persons, has resulted in a vast spectrum of new threats to what was once clearly personal and private information(15).” His research helps us see that there is no complete privacy when it comes to the internet any more. Our actions are always traceable, and thus easily interpreted for media entities.

Ess, C. (2014). Central Issues in the Ethics of Digital Media. In Digital Media Ethics (2nd ed., p. 15). Cambridge: Polity Press.

How might Facebook and other intermediaries influence the outcome of the 2015 UK election? Interesting @damiantambini https://t.co/VorI8BejyA

Policymakers should be considering the impact on media plurality of digital intermediaries such as Facebook https://t.co/pqdJxxtaa6 @iapem

Policymakers should consider impact on #media plurality of digital intermediaries like Facebook, says @damiantambini https://t.co/U8muExWAxh

Policymakers should be considering the impact on media plurality of digital intermediaries such as facebook https://t.co/TnKg0SXgRO

Policymakers should be considering the impact on media plurality of digital … – Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/3DqwsUOjkj #DoNoEvilTravel

Policymakers should be considering the impact on media plurality of digital intermediaries such as facebook https://t.co/31umnSbxgj