UK political elite networks are formed early in life and in specific fee-paying schools

What accounts for political elite formation in the UK? And what are the implications for democracy? Here, Brendan O’Rourke, John Hogan, and Paul F. Donnelly use a new ‘Institutional Influence Index’ to demonstrate the validity of the widely-held view that elite formation takes place early in life, and in specific fee-paying private schools such as Eton and Harrow.

The very existence of elites seems at odds with our democratic and egalitarian age, yet few would deny that elites, in the sense of small clusters of interlinked individuals with large and disproportionate power, exist. Some might even argue that cohesion among such groups makes for better and more coordinated decisions. However, such elites can be unrepresentative and out of touch. Such concerns were raised in Scotland’s recent referendum debate, and are likely to arise again in the upcoming UK election. Furthermore, as the recent financial crisis suggested, a group-think mentality can easily emerge among the elite, which makes risk and remedies, obvious to an outsider, unthinkable for a cohesive elite.

Social scientists and commenters have not neglected the topic of elites in recent years. Network analysis has allowed us to see the density of elite connections in a clearer way than ever before. There have also been insightful studies into elite formation, which is central to societal concerns about elites. While there may be tolerance for the emergence of an elite from diverse backgrounds, since it hints at a meritocracy, recent British debates about elites seem at their most passionate when places like Eton and Harrow are mentioned.

Nevertheless it has been hard to monitor elite formation. However, by drawing upon indices developed in other fields, we provide a set of indices that facilitates the comparison of elite formation systems. By using our indices to compare the role of post-primary education in the formation of cabinet ministers in Ireland and the UK between 1937 and 2012, we illustrate how elite formation systems can be monitored.

Measuring the influence and exclusivity elements of elite formation

Two aspects of elite formation institutions, like post-primary schools, are influence and exclusivity. The influence of particular institutions upon a specific societal group depends on the proportion of the elite affiliated with those institutions and the rarity of such institutions (for example, the percentage of UK cabinet ministers educated at the exclusive Clarendon Nine schools). The exclusivity of an institution is the degree to which being socialised there is an uncommon experience. We examine influence and exclusivity separately, before combining them to provide an elite index.

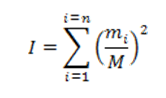

Our measure of influence, which captures both share size factor and the fewness factor, is an adapted version of the ‘Herfindahl Hirschman Index’ (H-Index) of market concentration. Thus, our Institutional Influence Index (I-Index) is measured by:

where mi is the number of affiliates (ministers) of the ith institute that are members of the elite in question and M is the total number of members (ministers) of that elite.

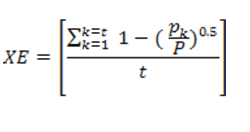

Measuring the exclusivity of an elite formation system is a little trickier. To reduce data requirements and focus on the elite formation element of exclusivity, we developed the XE-Index. Where P is the total relevant population, pk is the population in the kth elite institution, and t is the number of institutions producing members of the elite, then

This measures the exclusiveness of elite schools only, but also measures changes in both the proportion of the relevant population that goes to elite schools and how that proportion is shared among those schools.

Measuring the eliteness of formation systems

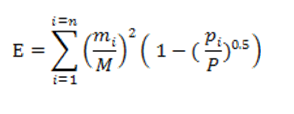

The elite index requires a measure that links exclusiveness and influence at the level of each institution, before aggregation to the level of the system. For this, the influence and exclusiveness measures can be combined into a linked Institutional Eliteness Index (E-Index):

Eliteness, influence and exclusiveness indices for post-primary schools in the UK and Ireland

Given that elite formation in the UK and Ireland is well studied, applying our methodology to these cases allows the robustness of our comparative measures to be examined in the context of previous work, which, while providing great insight, gave little quantitative grasp that was not immersed in contextual details.

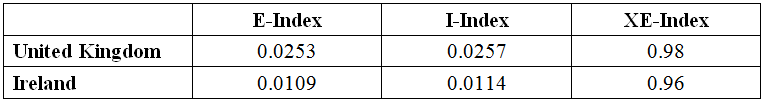

Table 1: Elite, influence and exclusiveness indices for Irish and UK post-primary school systems supplying cabinet ministers, 1937-2012.

From Table 1, we see that the E-Index for the UK is 0.0253 and 0.0109 for Ireland. The post-primary school system in the UK that produced cabinet ministers was more than twice as elite as the comparable Irish system.

In terms of influence, only a small percentage of secondary schools in the UK and Ireland provided ministers between 1937 and 2012, with even fewer providing more than one minister, and just a handful providing many ministers. The I-Index for the UK is 0.0257 and 0.0114 for Ireland. So, when it comes to the formation of the political elite, influence is much more concentrated in secondary schools in the UK than Ireland.

From Table 1, we see that the XE-Index for the UK is 0.98, while it is 0.96 for Ireland. The post-primary school system supplying cabinet ministers in the UK between 1937 and 2012 is just a little more exclusive than in Ireland.

Conclusion

In the case of the UK, our results underline the general view that elite networks, at least in politics, are formed rather exclusively and early in life in specific fee-paying schools.

Our indices allow for the measurement and easy comparison of eliteness and its constituent elements of influence and exclusiveness. This has the potential to allow for much more meaningful monitoring of how elites are formed in different societies. For a fuller description of our research, along with details of all calculations and supporting information, please see the full article in Politics.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

|

Brendan K. O’Rourke is a College of Business Research Fellow and Head of the Business, Society and Sustainability Research Centre at the Dublin Institute of Technology. |

|

John Hogan is a Lecturer in Irish Politics and International Political Economy at the College of Business, Dublin Institute of Technology. |

|

Paul F. Donnelly is a Research Fellow in Organisation Studies and International Business at the College of Business, Dublin Institute of Technology. |

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Bright and talented person with what it takes to lead our country to better days? What school did you go to? https://t.co/wVNZCx84e9

Daarom hebben we gelijke kansen onderwijs nodig: elite-netwerken worden vroeg in het leven gevormd in elite-scholen. https://t.co/Ggm8SwUkRX

‘UK political elite networks are formed early in life and in specific fee-paying schools’ https://t.co/NbtST4pmGJ [Democratic Audit UK]

#Elite formation takes place early in life and at key private schools like #Eton and #Harrow | via @democraticaudit https://t.co/sB4E1JvMkB

RT @kwr66: UK political elite networks are formed early in life and in specific fee-paying schools : Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/CyNHgz…

New research on elite formation in British and Irish schools, (hint not very different) https://t.co/Vh4K7ajdpd via @PJDunleavy

Brilliant hoax: “@PJDunleavy UK political elite networks formed early in life and in specific fee-paying schools https://t.co/g5I6SaptPi”

RT @PJDunleavy: UK political elite networks are formed early in life and in specific fee-paying schools https://t.co/Q04naBx0q1

Eliteness in British politics is formed in fee-paying schools according to academics writing in @democraticaudit: https://t.co/k8qvgCDGs0

#CompGov MT @HalaroseLtd: British political elites formed in fee-paying schools @democraticaudit: https://t.co/SVdQXJTJJH

UK political elite networks are formed early in life and in specific fee-paying schools https://t.co/F99D8rqNFo