If they want to prove to voters that they are ‘just like us’, politicians must embrace their flaws

UKIP’s victory at the Clacton by-election underlined the growing distance between mainstream politicians and a cynical and distrustful electorate. In the first of our post-party conference blogs on political and democratic reform, Andrew S. Crines from the University of Leeds argues that politicians need to rediscover the classic art of political rhetoric.

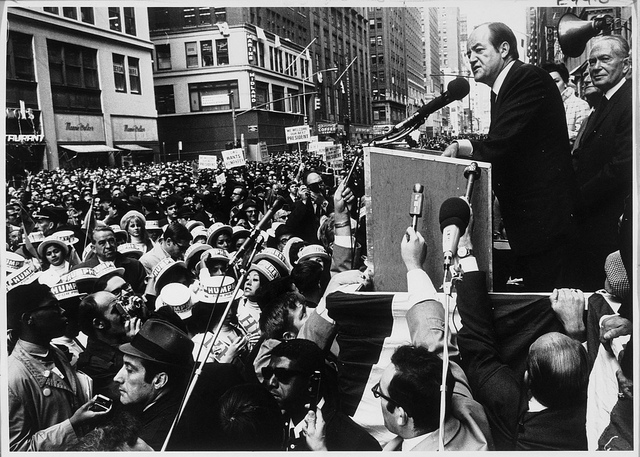

Credit: Keel Centre, CC BY 2.0

British Parliamentarians are under pressure like never before. The electorate demands more and more of them, while they face an ever increasing workload as a result of those growing expectations. It is a cycle of expectation that breeds cynicism and contempt, which is I dare say increasingly reciprocal. The view of the electorate that MPs are all self-serving and corrupt is validated by the actions of a sufficient number to make it appear endemic. These are then taken by the media to be representative of Britain’s political culture. Meanwhile those MPs who are hardworking find themselves the object of contempt. Whilst Bercow and others have striven to improve the image of MPs, the electorate continues to pour scorn over them for even the smallest infraction.

The importance of rhetoric

So, how can rhetoric assist? The academic study of political rhetoric breaks down communication into three core techniques – these are logic (logos), emotion (pathos) and character/credibility (ethos). Each of these should, ideally, be present in equal measure for a message to be convincing for an audience. However, therein lays the problem. Because for politicians this is not the case. The electorate tend to put the image of an ‘ideal’ politician on a pedestal, judging real life conduct against a very highly conceived Churchillian ‘leader’. Politicians are hence placed at an insurmountable distance from the third rhetorical prerequisite: ethos. Ethos is the most important rhetorical device because it enables a speaker to connect with an audience. Ethos demonstrates their character and credibility.

‘Just like us?’

So what consequence does this difficulty in demonstrating ‘ethos’ mean practically? Put simply, politicians are unable to demonstrate to the electorate they are ‘just like them’. Without being able to do so hardworking MPs find themselves at a distance from the electorate through no fault of their own. Politicians simply are unable to demonstrate their character or credibility because the electorate has placed expectations upon them that few could meet. Matthew Flinders refers to this as ‘the expectations gap’. The rhetorical impact of this trend renders the use of the other devices redundant. This is because if the electorate will not accept that politicians are just like them, then they will not listen to the logic of an argument, or become emotionally engaged. This is a highly problematic issue for the health of democracy.

What is to be done?

Financial scandals, over professionalisation, apparent ideological convergence, and the perception of ingrained corruption (some real, some media manufactured) have over decades confirmed – rightly or wrongly – that politicians are not like the citizens they represent. This is a major issue which needs to be addressed. Should politicians show that they are ‘just like us’ and that they share the same concerns as the broader electorate then they may be able to inspire greater trust. Beyond professionalisation, the personalisation of politics may enable political elites to demonstrate their rhetorical ethos to the electorate.

In rhetorical terms, personalisation is about showcasing ethos by highlighting the basic fact that politicians are human too. They have personal flaws, worries, and desires. In speeches and media appearances politicians should project these desires, flaws and worries, rather than seeking to cover them up with overly stylised and polished performances. This is a strategy already successfully employed by Nigel Farage, and has historically been useful by politicians such as Harold Wilson. Flaws are character traits which can appeal to the electorate because it demonstrates normalcy.

In contrast, professionalisation is about projecting a clean image, but this has partly undermined the trust of some of the electorate because it feels manufactured. Personalisation of this kind, however, would begin to turn the tide of distrust which is being repeatedly perpetuated by a minority of MPs who appear either distant or aloof. Should this fail to happen, however then politicians will not be in a position to regain their ethos, and with it will lack the credibility and character needed to convince the electorate of their arguments.

—

Note: this article gives the views of the author, and not the position of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. It originally appeared on the Crick Institute blog. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Andrew S Crines researches oratory and rhetoric in British party politics at the University of Leeds. He has co-edited with Richard Hayton two volumes focused on oratory in Labour and Conservative party politics respectively, and he has also published in a wide range on academic journals. Andrew is also the Publicity Officer of the PSA Conservatives and Conservatism Group. He tweets @AndrewCrines

Andrew S Crines researches oratory and rhetoric in British party politics at the University of Leeds. He has co-edited with Richard Hayton two volumes focused on oratory in Labour and Conservative party politics respectively, and he has also published in a wide range on academic journals. Andrew is also the Publicity Officer of the PSA Conservatives and Conservatism Group. He tweets @AndrewCrines

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

In order to reconnect with voters, politicians must embrace their flaws: https://t.co/BJYCWxayo7

Politicians must embrace their flaws and demonstrate to electorate they are ‘just like them’, argues @AndrewCrines. https://t.co/KbT2IGQKXz

If they want to prove to voters that they are ‘just like us’, politicians must embrace their flaws https://t.co/NXbfddorfv

If they want to prove to voters they are ‘just like us’, politicians must embrace their flaws https://t.co/9oEnY2dR9v https://t.co/h9pCFkPDsV

If they want to prove to voters that they are ‘just like them’, politicians must embrace their flaws https://t.co/Oy0jXIlAqz