The complexity of a party system does not affect the ideological compatibility of voters and political parties

In multi-party political systems, it has been argued that voters have more difficulties in matching their own programme with that of a political party. Joris Boonen, Eva Falk Pedersen and Marc Hooghe argue that there are differences between countries, but these are not explained by the complexity of the party system: the number of competing parties is not significantly related to the degree of ideological compatibility between voters and parties in a country. On the individual level, they find that political knowledge increases the ideological congruence between voters. Furthermore, voters with strong party attachments seem to be less ideologically close to the party they intend to vote for than independents.

The Dutch Parliament (Credit Michiel Jeiljs, CC BY 2.0)

Making a ‘rational’ vote choice based on the correspondence between the standpoints of the party and one’s own standpoints requires that voters have clear preferences and that they are able to match their ideological position to that of at least one of the parties. This exercise has shown to require a high level of political sophistication. Particularly within the highly fragmented context of many contemporary democratic systems, less experienced, less knowledgeable and less interested citizens have been experiencing difficulties in matching their own preferences to a specific political party or candidate.

The bulk of previous research on the congruence between voters and parties uses aggregate comparisons between the ‘mass’ and the ‘elites’, for instance on the importance of the electoral system or the party system for representation. It is essential to study this compatibility, or ‘congruence’ at the level of an individual voter as well, because these aggregate comparisons do not give us information on the individual dynamics that determine to what extent voters chose a party that is ideologically close to themselves.

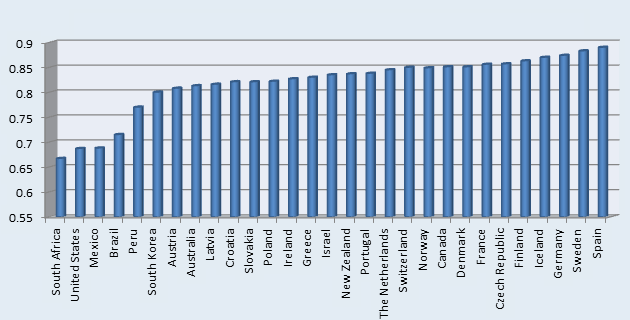

To study this, we use data from Module 3 of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES), a large scale cross-national election study. For all voters in each participating country, we have calculated the correspondence between the voter’s left-right placement and the left-right placement of the party voted for (reversely scaled from 0-1).

The smaller the distance between both, the higher the ideological congruence in our analyses, with a score of 1 indicating a perfect match between the voter and the party.

The number of parties does not affect party-voter congruence

Following earlier research, we expected that the composition of the party system affects the congruence between voters and parties. This hypothesized relationship has been interpreted in two ways. One the one hand, proportional electoral systems have the advantage that a larger number of parties fills the electoral space, and as a voter, this should increase the chances of finding a party that is ideologically close to you. On the other hand, the larger the number of parties competing in an election, the higher the complexity for voters. To be well-informed, voters need to gather more information, which can actually decrease the chances of voting for the party that is ideologically closest to you.

In our analyses, there are indeed quite some substantial differences between the countries. The United States, for instance, has one of the lowest mean congruence scores (.69), while the congruence score in the Netherlands, one of the most fragmented party systems, is .85. Spain has the highest level of congruence between voters and parties in this sample, with a mean congruence score of .89. But these differences do not follow a clear pattern in the sense that there is no significant relation between the number of competing electoral parties and party-voter congruence.

In terms of substantive representation, our analyses suggest that the choice for a proportional (more chances for smaller parties) or plurality (nearly only larger parties are viable) electoral system does not affect the ideological link between voters and parties.

Figure 1: Mean congruence score per country

Note: Figures from most recent election in the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (Module 3)

Political knowledge increases ideological congruence between parties

Political knowledge was expected to increase ideological congruence, as in previous studies it has been argued that political knowledge is essential to make vote decisions in a well-considered way. Our analyses confirm this idea and show that voters with a higher level of political knowledge are indeed more likely to choose a party that is ideologically closer to them.

This provides us with an additional argument as to why political knowledge is essential for a healthy electoral democracy. Particularly in the light of concerns on growing unawareness of younger citizens of traditional party politics, these analyses suggest that growing unawareness can indeed jeopardize the mechanism of substantive representation of public interests through elections.

Less congruence among strong party identifiers

A final determinant that we expected to be related to party-vote congruence is party identification. Following the initial conceptualization of party identification in the American Voter, it can be seen as an individual’s affective orientation to an important group-object in his environment. In our analyses, we observed an interesting relationship between party identification and congruence. When compared with weak or non-identifiers (independents), voters with a strong party identification seem to have a lower level of ideological congruence between themselves and the party they vote for.

Although this might seem counterintuitive, it is in line with what we could expect from the literature on party identification. Instead of being socialized into strongly identifying with one particular party and also voting for this party, independent voters seem to make a more rational choice in the sense that it is more congruent with their own ideological preferences.

The major lesson to be learned from this analysis is that there is no reason to prefer relatively simple party systems (e.g., two major parties) in comparison to complex, multi-party systems. In both kinds of party systems, voters seem to have the same possibilities to cast a congruent vote, i.e. a vote that reflects most closely their own ideological preference. While intuitively, one would expect that this process is more difficult in a complex multi-party systems, apparently voters still manage to find their way to the party that is indeed closest to their own ideological preference.

—

Note: This piece is a summary of a working paper that was presented at the annual Elections Public Opinion and Parties (EPOP) conference, entitled “The influence of political sophistication and party identification on party-voter congruence: a comparative analysis.” It represents the views of the authors, and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

|

Joris Boonen is a PhD candidate at the department of Political Science at the University of Leuven (Belgium). His research is mainly focused on the development of party preferences among adolescents and young voters. Previously his work has been published in Electoral Studies, Youth & Society and Nations and Nationalism. |

|

Eva Falk Pedersen graduated of a Master’ degree in political science at McGill University. She now works as a research assistant. Her research is mainly focused on voting behaviour and political participation. |

|

Marc Hooghe is a professor of political science at the University of Leuven (Belgium) and a visiting professor at the Université of Lille-II (France). He holds an ERC Advanced Grant to investigate the linkage between citizens and the political system. |

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Moving to more complex party system does not affect the ideological compatibility of voters and political parties https://t.co/jPoCUz8NRl

The complexity of a party system does not affect the ideological compatibility of voters and political parties https://t.co/8JRNmQ4vx0

The complexity of a party system does not affect the ideological compatibility of voters and political parties https://t.co/5TmpawQhve