The UK should urgently legitimise the revocation of UK citizenship to the Islamic State’s British members

The Islamic State has recently taken control of huge swathes of the Middle East, with British citizens thought to be amongst those involved in the violence. Simon Hale-Ross argues the European Union must stop dwelling on the human rights issue and adopt the directive dealing with Passenger Name Records, and the UK must seek to legitimise the removal of UK jihadist passports.

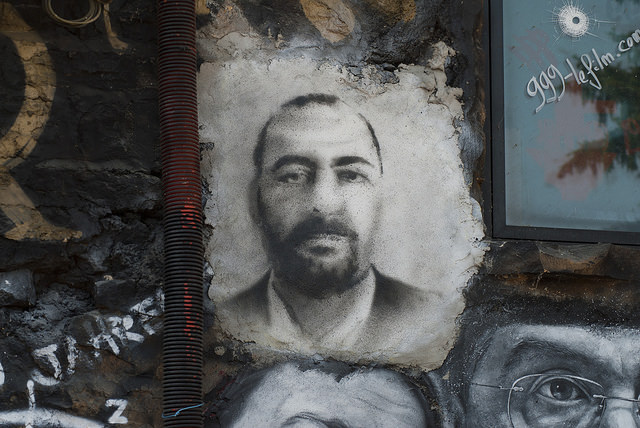

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the Leader of the Islamic State (Credit: thierry ehrmann, CC BY 2.0)

An international collaborative approach is vital to combat the international terror threat posed by IS jihadist members. The European Union must stop dwelling on the human rights issue and adopt the directive dealing with Passenger Name Records, and the UK must seek to legitimise the removal of UK jihadist passports.

The seriousness of the threat posed to the UK and the European Union, from their own citizens who subscribe to the Islamic State’s (IS) ethos, and have additionally been fighting with them cannot be overstated. Their religious beliefs are medieval rendering negotiation pointless and ineffective, the ideology of the group is dangerous and destabilising, and the political aspirations and actions are abhorrent. They have been described as a cancer and will not rest until they attain their objective.

The catalyst for these new heightened debates was the Joint Terrorism Analysis Centre’s (JTAC) raising of the UK’s terror threat level fromsubstantial to severe, meaning that at attack is now highly likely. This was evidently in direct response to the approximated 500 UK British citizens currently fighting with the jihadist terror group the Islamic State (IS), formerly known as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria/Levant (ISIS/ISIL), in conjunction with the publication of the brutal beheading of the US journalist James Foley, an act committed by a terrorist with a British accent. Although such beheadings and slaughter of Iraqis has been going on for quite some time, this incident authenticated concerns at home for many westerners.

This has prompted the UK government to propose new legislation creating a new legal framework to remove passports from UK citizens. The controversial debate surrounding airline data sharing with intelligence officials has also returned, with David Cameron pressing the European Union to enact a directive, thus harmonising the legal response across the 28 Member States. Cameron irrefutably knows that a domestic measure alone will prove inadequate.

Dealing with the removal of UK citizens’ passports first, it is clear the possibility of effectively rendering a person stateless is growing. The legality of such a response is another matter entirely. There are two United Nations (UN) Conventions that the UK has long been a signatory, one of which serves to prevent a State from rendering a citizen stateless. The Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons 1954 and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. The 1961 Convention represents an international instrument safeguarding citizens from inappropriate and unfair threats of statelessness. The Home Secretary, using Royal Prerogative power can revoke a person’s UK citizenship entitlement, so long as the person concerned holds a duel nationality. The two issues facing the government are; the need to place this power on the statute book, carefully worded to reduce judicial intervention; and how to legitimately remove a UK only citizens passport, rendering them stateless.

This is where David Cameron’s dexterity can be perused in his use of words, describing the actions of UK citizens fighting for IS, as disloyal. Articles 8 and 9 of the 1961 Convention expressly forbid the deprivation of nationality on racial, ethnic, religious or political grounds. Although the religious beliefs and political aspirations shown by members of IS are abhorrent, this would appear to satisfy the above definition. However, under the Convention, if a citizen has committed acts inconsistent with the duty of loyalty to the State, the State retains the right to deprive that citizen of nationality, even if this leads to statelessness. Proportionality and due process are the key terms that new UK legislation must conform, adhering to these safeguards. Should such wording be carefully expressed, satisfying the UK’s international obligation to the UN and additionally the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the legitimacy of rendering a person stateless may be made possible.

The further issue deals with the debate surrounding the sharing of the Passenger Name Record (PNR) with intelligence agencies and officials. Such data is already accessible by UK counterterrorism officials, evidenced by the Miranda debacle in August 2013. However, no EU wide legal consensus exists, with the subject proving to be a divisive sticking point for the current negotiations between theCommission, the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament. The PNR tends to include not only names, addresses and merely meal choices, but credit card details and phone numbers, and potentially sensitive data on ethnic origin, health, political views and sexual orientation. Because of such sensitivity one can understand MEP’sconcerns with regards to data protection and civil liberties, however, such information would only be made available to counterterrorism agencies and used in accordance with the law. The States primary charge is to safeguard its citizens. Indeed, one cannot seek to enjoy qualified human rights (Article 8-11 ECHR) without the absolute rights being protected, such as Article 2 ECHR Right to Life.

Despairingly, the EU, despite pressure from the UK and other Member Sates, cannot approve a directive legitimising PNR sharing, yet decisively agreeing to share such data with the US in April 2012. Additionally, Canada is now waiting for approval from the European Parliament to also share such data.

A EU directive covering PNR information, made available in real time will provide the security services with exceptional opportunities to stop and search, question and detain terror suspects. It would mean that terror suspects would find it extremely difficult to travel around the EU without being detected. In the UK, police powers regarding passenger and crew information are regulated by section 32 of theImmigration, Asylum and Nationality Act 2006. The requirement to provide PNR can only be imposed in writing and by a police officer if he thinks it is necessary in the prevention, detection, investigation or prosecution of criminal offences, or for safeguarding national security. The problem here is that the police require prior intelligence to suggest a particular suspect is travelling to or from the UK. With recent reports suggesting up to 250 UK citizens are believed to have returned home after fighting with IS, travelling through Germany and Turkey, the need to improve the situation is clear particularly when contemplating the UK are somewhat uncertain as to who the potential 250 UK citizens are. As Turkey is not a EU Member State, further agreements are required in addition to the directive.

An immediate adoption of the EU directive is paramount in providing a common framework between EU Member States in releasing the PNR, in real time, to ensure the safety of citizens from terror attacks carried out by returning IS jihadist fighters. The problem of international terrorism is not limited to the UK and requires an international response. Mehdi Nemmouche, a French national evidences this, killing three people at a Jewish Museum in Brussels earlier this year, after returning from spending a year in Syria fighting for ISIS/ISIL. Considering EU directives allow the Members States some time to successfully implement new legislation, the sooner the EU agree the better.

Passport removal must also be carefully considered as an option and David Cameron has made it clear that the proposed powers will be specific and not representative of a knee jerk reaction. Since the release of the video showing the brutal beheading of James Foley in August, Steven Sotloff has become the latest victim, murdered by the same British jihadist with a further warning accompanying the grotesque killing.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Simon Hale-Ross is a PhD candidate in law and part-time lecturer at Liverpool John Moores University, having previously studied there for a Bachelor in Laws with Honours.

Simon Hale-Ross is a PhD candidate in law and part-time lecturer at Liverpool John Moores University, having previously studied there for a Bachelor in Laws with Honours.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

The UK should urgently legitimise the revocation of UK citizenship to the Islamic State’s… https://t.co/hysdzJ1yN3

The UK should urgently legitimise the revocation of UK citizenship to the Islamic State’s British members https://t.co/15FzlfPesd

What would you propose as the basis for the invocation of such powers? In other words, would you support the removal of ones citizenship merely for travelling to certain countries? Would evidence of intent/interaction/engaging be required? How would an individual challenge the actions of Government? Who would pay?

I would suggest that these are just a handful of difficulties that may ultimately preclude their use. That is not to say that we do not need to do more to guard against the threats posed by IS and particularly those leaving the UK to join the fight – rather that we should perhaps be a little more innovative than imposing an arbitrary one-size-fits-all decitezenship measure.

Even if we sidestep the issue of human rights and the moral legitimacy of removing citizenship (regardless of the individual case in question), there are two problems with urging Cameron to press ahead with this plan to remove passports from UK citizens:

1. Evidentiary – what seems to be proposed is removal of passports without much judicial scrutiny, largely on the suspicions presented by branches of the executive – being suspicious is part of their job. The individual in question will, presumably, be out of the country and unable to mount much of a defence (if they are aware of the proceedings at all). How sensitive can this procedure really be without balance? How will the intelligence agencies discern the difference between someone who travels to Syria to fight and an individual, maybe someone with familial connections, who goes to provide aid/relief to their community? Call me old fashioned, but if the security services are aware of an individual who has associated with IS, is now back in the UK and is planning a terrorist atrocity, what is to stop justice being done the traditional way – by taking them to trial, and, if the charges are proven, putting them behind bars? (Admittedly my legal knowledge is rudimentary here, but if a crime has been committed, the state is empowered to act, surely….)

2. What effectiveness will this policy have in the long term? It smacks, really, of reactionary, on-the-fly, policy making by a government interested in appeasing the media. Refusing return to (ex-) British fighters may prevent them from launching attacks in Europe – although finding ways to enter the country illegally is hardly beyond the wit of man. But it does nothing – absolutely nothing – to address the problem of UK citizens going abroad to take up arms, or to stop the violence in Iraq/Syria. Those who are out there fighting will remain out there. Moreover, it’s hardly necessary to travel to Syria to become radicalised and drawn into terrorist activities – the 7/7 bombers were famously “home grown” terrorists. If the government is truly interested in stopping the abhorrent conflict in Iraq/Syria, or in dissuading UK citizens from participating in it, what’s needed is a careful look at what makes IS’s message appealing to certain individuals.

Simon Hale Ross makes the case for the UK Government to strip ISIS members in the UK of their passports https://t.co/p9o0IVkUwq

Britain’s ISIS fighters should be stripped of their citizenship, says Simon Hale-Ross https://t.co/U6h0f8crNq

The UK should urgently legitimise the revocation of UK citizenship to #IS’s British members https://t.co/MqWD5H0epB https://t.co/KBe6werwjw

The UK should urgently legitimise the revocation of UK citizenship to the Islamic State’s British members https://t.co/ImSpBk9xVu