Survey research suggests that ‘ever looser union’ is the direction of travel for the UK

The debate in the Scottish independence referendum suggests even a no vote will be followed by greater autonomy for Scotland. In Wales, too, the National Assembly has extended its powers and may continue to do so, while England is also seeing clamour for devolution. In this post Richard Wyn Jones questions whether the UK’s institutions can respond to the desire for weaker ties between the home nations.

Is the United Kingdom destined to become an ever looser union? Credit: National Assembly for Wales CC BY 2.0

While the referendum will pose the choice facing the Scottish electorate as one between independence and the status quo, the surrounding political campaigning poses the choice in different terms: between independence and further self-government. This was presaged in a carefully worded statement in Edinburgh in February 2012 by Prime Minister David Cameron, who strongly implied that a ‘No’ vote would lead to further devolution. The Unionist political parties have all established various internal processes aimed at formulating their own enhanced schemes. Indeed, it appears that there are moves afoot behind the scenes to try to agree a joint-unionist alternative offer to be announced before the referendum. To the extent that a positive case is being put forward for the Union, it is for a Union in which the already powerful devolved Scottish parliament enjoys more autonomy and control over Scottish life.

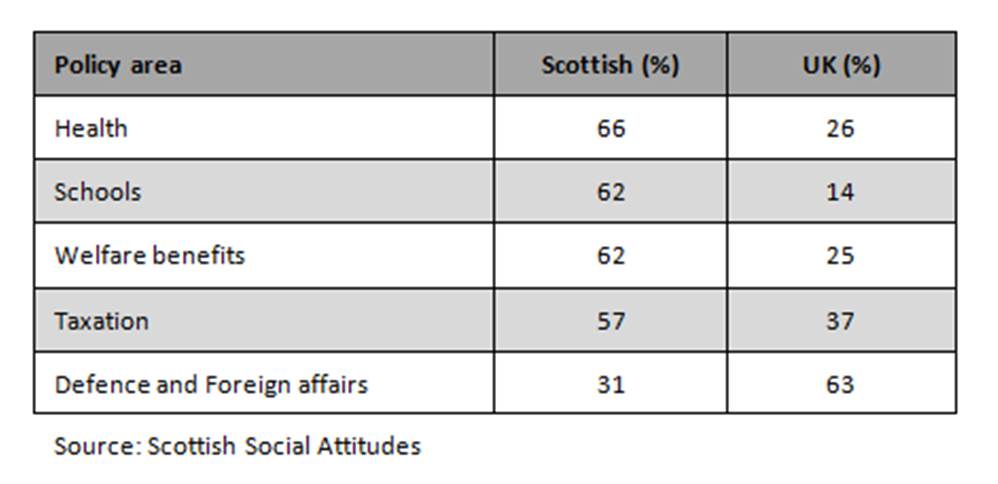

The reasons for this become apparent on perusal of the polling evidence. Opponents of independence do not tire of pointing out (quite correctly) that there is no evidence that there has ever been more than minority support for such an outcome among the Scottish electorate. But even if they are more reticent of admitting it in public, they are also well aware that the constitutional status quo also enjoys only limited support. Rather, survey after survey demonstrates that the overwhelming majority of Scots wish to see their devolved parliament enjoy substantially more powers. Indeed, it appears that only in the case of foreign and defence policy competences do we find a majority of Scots believing that competence should remain at the Westminster level (Table 1). If these sentiments are not somehow assuaged then unionists are in danger of winning the battle but losing the war.

Table 1: Scotland: Which level of Government should have most influence over the following policy areas, 2012

Herein lies the rub. Viewed in retrospect, the Unionists’ most recent attempt to redraw the Scottish settlement – via the Calman Commission and the subsequent 2012 Scotland Act – was poorly judged. It produced a financial package that appears to have been designed to force the Scottish authorities into taking politically contentious decisions, while at the same time granting them little or nothing by the way of additional, genuinely usable policy autonomy. So while the Scottish parliament will now have no option other than to take decisions on tax rates in Scotland – in itself, an entirely sensible development – it has not been entrusted with the ability to vary any changes between tax bands. This is hardly the kind of arrangement that one would associate with a genuine attempt at empowerment. This impression is confirmed when it is also recalled that, beyond the financial aspects of the settlement, the headline ‘extra powers’ granted to Edinburgh were over air guns and speed limits: important in their way, no doubt, but small beer in constitutional terms.

Will the Unionists do better this time? They surely have the incentive to do so. This is hardly the time for niggardly attitudes. But they also face genuine dilemmas, especially if as seems to be the case, they are determined to maintain cross-party unity while doing so. Not least because devolving significant elements of Welfare appears anathema to Labour, even while it rails against the various reforms and cuts being introduced by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat UK coalition government. Moreover, even if they can agree and enact a more generous dispensation, it appears almost certain that it will fail to match the aspirations of the Scottish electorate. Assuming Scotland stays in the Union, its relationship with the central state will be looser than has been the case until now, and that there will remain substantial pressure for yet further devolution of power.

Wales

Given the relative lack of interest even at the prospect of Scottish independence, it is no surprise that developments in Wales enjoy even less prominence in the London media. Yet between 1999 and 2011, at least, it was Wales that provided much the most dramatic changes in both public attitudes and institutional architecture across the post-devolution UK.

From very unpromising beginnings, characterised by weak public support and a constitutional design that proved to be utterly inadequate, the National Assembly for Wales has rapidly gained both popular legitimacy and additional powers. This culminated in a very one-sided referendum campaign in March 2011 fought on the issue of additional powers. A referendum that saw an easy victory for the pro-devolution camp, with their opponents reduced to a small, rather chaotic rump.

Yet passing that milestone appears to have done nothing to quieten the clamour for further devolution. Rather, the Silk Commission, established by the UK government in October 2011, has already recommended the devolution of tax and borrowing powers to Wales, in terms that are broadly analogous to those recommended to Scotland by the Calman Commission. Following an apparently fractious period of inter-coalition wrangling, the UK has recently announced that it will be implementing most of the Silk recommendation. While Silk’s insistence that a referendum be held before income tax can be devolved – coupled to the very obvious reluctance of the Wales Labour Party to hold such a poll – means that the key element of the package is likely to remain unimplemented for the foreseeable future, the very fact that a Conservative-led administration is pushing devolution forward is in itself a remarkable development.

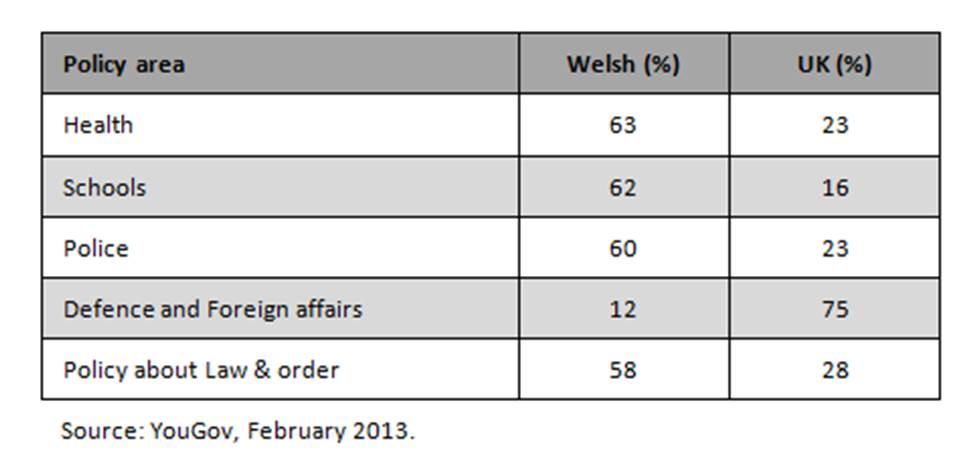

Meanwhile the Commission itself has turned its attention to the second part of its mandate, and is considering the Welsh devolution dispensation more broadly. The Welsh Government has taken the opportunity to call for further, substantial changes. These involve, in part, correcting the continuing inadequacies of the Welsh dispensation, by moving from a ‘conferred powers’ (as envisaged for Scotland in the 1978 Scotland Act) to a ‘reserved powers’ (as eventually implemented by the 1998 Scotland Act) model of devolution. But in addition, Cardiff has called for the devolution of policing and – as a longer-term objective – criminal justice as a whole. As can be seen from the opinion poll evidence in Table 2, both these developments apparently enjoy strong support among the Welsh electorate at large. Other ideas put forward to the Commission include the establishment of a separate legal jurisdiction for Wales, and (by the Conservative opposition in the National Assembly, no less) the devolution of broadcasting. While there is no direct evidence of public attitudes on these latter possibilities, it is nonetheless clear that, among both the Welsh political class and the population at large, the appetite for the further devolution of power is far from sated. Even if the country’s parlous economic condition means that there is far less appetite in Wales than in Scotland for devolving Welfare functions, it is nonetheless clear that the country’s future relationship with the UK state will be characterised by greater autonomy and self-government. In other words, a looser Union.

Table 2: Wales: Which level of Government should have most influence over the following policy areas, 2013

England

Until recently the perception had been that the English viewed the devolution process across the rest of the UK with what might be termed benign indifference. Broadly speaking they were relaxed about developments elsewhere in the state, so long as they continued to be governed by the familiar institutions of Westminster and Whitehall. This prevailing wisdom has been challenged by research carried out by a team from Cardiff and Edinburgh Universities and the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR), under the banner of the ‘Future of England Survey’ (see an overview of the survey results).

Whatever the situation that pertained in the early years of devolution, it appears support in England for the territorial status quo has now fallen dramatically to no more than 1 in 4 of the population. In the context of a widespread perception that it is unfairly treated following devolution (what we have termed ‘devoanxiety’), it appears that a majority wish to see England explicitly and positively recognised by the governmental system, rather than the present situation of being a kind of residual category left over as a result of devolution elsewhere. There is, however, no consensus as to what form such recognition should take.

Not only that, but it appears that English national identity is being politicised. The more exclusively English a person’s sense of national identity, or the more strongly the English element of a joint or ‘nested’ Anglo-British identity is stressed, the more likely a person is to feel that England is unfairly treated by the current arrangements, and the more strongly they want to see a positive recognition of England qua England by the political system.

English dissatisfaction with the internal territorial constitution of the UK is also, it transpires, closely related to dissatisfaction with the state’s external relationship with the European Union. Thus, even if Eurosceptic rhetoric posits ‘Europe’ as a threat to British values and traditions, it is in fact those who feel most exclusively English that are more hostile to the UK’s membership of the EU. Indeed, counter-intuitive though it may be to many, the most exclusively British a person’s sense of national identity the more pro-European they tend to be.

The overall picture emerging strongly from the latest research is therefore of significant English discontent with both of the political unions of which their country is a part: with the United Kingdom as well as with the European Union. All of which suggest not only that pressure will continue to mount for an attempt, at least, to develop a looser relationship between the UK and the EU (as already promised by David Cameron), but also that pressure to redraw relationships within the UK in ways that grant the various national units more autonomy will emanate not only from Scotland and Wales, but increasingly from England too.

All of which poses a profound challenge of political and constitutional imagination. Can the institutions of the UK state actually adapt in ways that would give expression to the apparent public desire for ‘Ever looser Union’? Thus far the devolution process, while leading to radical if not revolutionary changes at the periphery, has left those central institutions almost entirely unchanged. So, for example, even the UK government’s territorial offices for Scotland and Wales have survived, even if it is hard to fathom how this could possibly be justified now those nations have their own law-making parliaments and powerful governments. But a further, more generous package of devolution to Scotland, in particular, would surely require major reforms at the centre –up to and including a written constitution – in order to ensure the proper functioning of what would then be a highly decentralised state.

In their way, however, England and English sentiments provide an even more profound challenge to the state. If the current fusion of UK and English functions in UK-level institutions is somehow brought to an end – which is, after all, what an increasing proportion of the English population seem to want – then institutionally speaking, everything would change. Indeed, while our attention will naturally focus on Scotland over the coming year, English discontent with both of the Unions of which England forms a part may well ultimately prove a greater threat to the state than nationalist sentiment north of the border.

—

Note: This post represents the views of the author and does not give the position of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before commenting. Shortlink for this post: https://buff.ly/1eGj9xz

—

Richard Wyn Jones is Director of the Wales Governance Centre and Professor of Welsh Politics at Cardiff University. In May 2013, he participated in a conference held at the British Academy on ‘Welsh Devolution in Perspective: Wales, the United Kingdom and Europe’ which forms part of a report produced in partnership with the Learned Society of Wales: Wales, the United Kingdom and Europe.

Richard Wyn Jones is Director of the Wales Governance Centre and Professor of Welsh Politics at Cardiff University. In May 2013, he participated in a conference held at the British Academy on ‘Welsh Devolution in Perspective: Wales, the United Kingdom and Europe’ which forms part of a report produced in partnership with the Learned Society of Wales: Wales, the United Kingdom and Europe.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Scotland ‘leaving’ the UK would make little difference. Wales or N.Ireland ‘leaving’ the UK would be an insignificant event. England ‘leaving’ the UK would be a seismic event and would in reality herald the end of the UK. What would remain? A celtic/protestant fringe.

Many English people have become increasingly frustrated by the attitude of the other nations of the UK and of the British and many would be pleased to see England declare independence.

All I can hear are the voices of Scots and Welsh debating the future of Britain. There is a much larger population that do not want to argue detail they want it scrapped. AND scrapped it will be! As a famous Englishman Mr G. K. Chesterton said:

But we are the people of England; and we have not spoken yet.

Smile at us, pay us, pass us. But do not quite forget.