Social media helps forge links with voters, but the ‘ground war’ remains much more important for election campaigns

The question of whether web 2.0 technologies work in ‘getting out the vote’ is one that remains the subject of some debate. In the latest post of our Democracy Online series, Professor Rachel Gibson outlines new research suggesting that while online has a role in reaching voters, traditional methods still remain powerfully persuasive.

Traditional methods of engaging voters are more persuasive in encouraging turnout. Credit: Dieter Zirnig (CC BY-NC 2.0)

The arrival of email and the Internet – and more recently web 2.0 technologies – has provided political parties and candidates with a whole new suite of faster and more personalised ways to engage in voter contacting. Our research in collaboration with Duke University – and funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) – has been attempting to find an answer to the question of whether social media tools work in ‘getting out the vote’.

The central objective of ‘Campaign Mobilisation in the Social Media Era’ is to further our understanding of how the quality, quantity and effects of campaign contacting are changing as a result of the use of social media by parties, candidates and their supporters.

Specifically, we advance the argument that online tools are increasing not only the amount of contact that voters receive in elections encouraging them to vote but also its mobilising effects. We make this claim based on the viral properties of the digital medium and its increasingly socially networked basis which make contact faster, more widespread and more likely to be mediated through friends and family.

Our work is highly significant given the concerns that have been raised over falling rates of voter turnout and attachment to parties and politicians within Western democracies and the US and UK in particular. Based on our findings we will be able to provide new systematic insights for academics and practitioners into the extent and effectiveness of traditional versus new online forms of voter contacting, and what works best to stimulate political engagement. The comparative element of our research is useful in that it will allow us to also examine whether the context and particular nature of elections and party system affects the rate and impact of these contacts.

So what does our work so far suggest? Well, we have found that the older methods still remain significantly more powerful in getting voters to the polls than newer digital channels. But online contacting does appear to have a role in maintaining and reinforcing a link with voters and supporters that are already active in helping the campaign effort.

We used a combination of national election survey data from the US and the UK to compare the effects of the different types of campaign mobilisation. This included the American National Election Study (ANES), the British Election Study (BES) and a special ESRC-funded survey of online political behaviour conducted for the 2010 UK parliamentary elections conducted by the polling company BMRB.

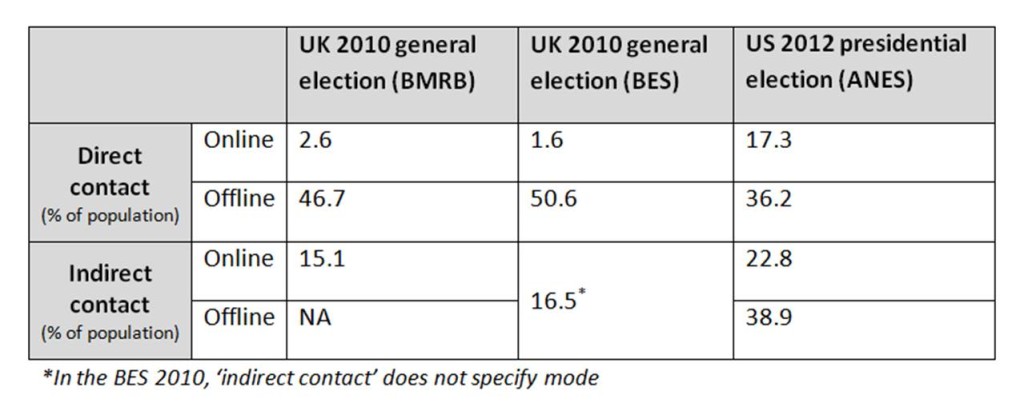

Table: Percentage of citizens contacted in the last elections in the UK and the US

Aside from confirming the power of more conventional offline methods for mobilising voters the results did show that levels of online contact were quite different across the two countries, as shown in the table above. In the US around 17 per cent of the population reported some type of online contact from a candidate or party in the 2012 Presidential election – either through email, Facebook or the Web more generally. In the UK the proportions were substantially lower at just over two per cent of voters reporting such contact. The longer US campaign may of course account for the differences but the almost eight-fold increase in the American race does send a clear signal that the medium is taken more seriously by US campaigners.

This picture is changed somewhat when rates of indirect online contacting are considered – messages sent by friends and family on Facebook or email to persuade you to vote for a particular candidate or party. When the researchers considered this more personalised method of campaign contact they found a greater parity between the UK and US with just over one fifth of the US sample reporting receiving such messages, while around 15 per cent of UK respondents had received this type of prompt.

The conclusions raise something of a challenge to the recently highly publicised results of a 61-million-person Facebook experiment conducted by Bond et al. in the US (2012) and reported in Nature that showed messages mediated through online social networks have a small but significant effect on voter turnout. More generally the findings confirm that the ‘ground war’ is still the place where a campaign needs to be fought if it wants to maximise its support.

Note: An earlier version of this post was published on Manchester Policy Blogs’ Westminster Watch. The table is drawn from a paper by John Aldrich, Rachel Gibson, Marta Cantijoch and Tobias Konitzerv presented at the ‘Voter Mobilisation in Context’ workshop in Manchester, 8 November 2013.

This post represents the views of the author, and does not give the position of Democratic Audit or the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting. Shortlink: https://buff.ly/1aQsfDv

Professor Rachel Gibson is the Director of the Institute for Social Change at the University of Manchester. Her research interests include new media, political parties and citizen participation, the professionalisation of political campaigning, Web linkage analysis and methodologies to map online political networks and design and analysis of social attitude surveys and election studies.

Professor Rachel Gibson is the Director of the Institute for Social Change at the University of Manchester. Her research interests include new media, political parties and citizen participation, the professionalisation of political campaigning, Web linkage analysis and methodologies to map online political networks and design and analysis of social attitude surveys and election studies.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.