Lord Armstrong’s EU Bill Amendment shows the way forward for the framing of referendum questions

The Conservatives EU Referendum Bill fell in Committee stage in the House of Lords, meaning that there is likely to be no referendum on the statute book before the next election. During the Bill’s hearings, Lord Armstrong proposed an amendment to the wording of the proposed question, which took up the suggestions of Democratic Audit and the Electoral Commission, says Sean Kippin.

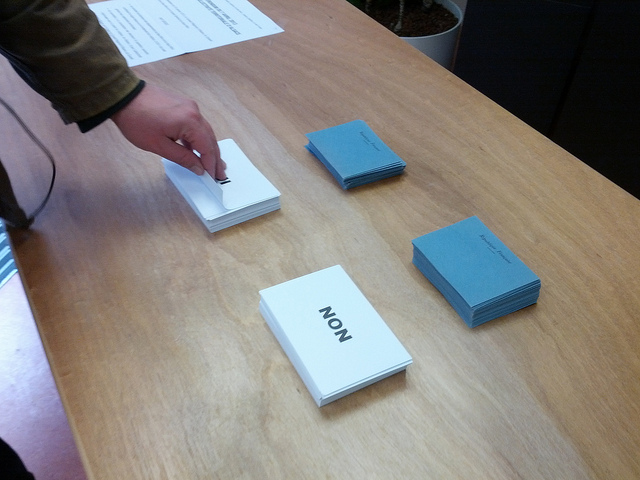

On January 24th, the former Cabinet Secretary Lord Armstrong tabled an amendment to the Conservative MP James Wharton’s European Union (Referendum) Bill 2013-14 which would have changed the proposed wording of the referendum question from;

Do you think that the United Kingdom should be a member of the European Union?

To;

Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?

While this change may appear to be relatively minor, there was a genuine risk that the original formulation could lead referendum voters to mischaracterise the UKs current relationship with the European Union, leaving it unclear as to whether the UK is currently a member. As Democratic Audit’s co-Director Patrick Dunleavy argued in July of last year

This question is highly misleading in two dimensions. First, it implicitly suggests to voters either that the UK is not already a member of the European Union, or [second] that our membership is up for renewal in some kind of routine, regular or unprompted way.

This observation was taken up by the Electoral Commission, in the organisation’s evidence to Parliament. They noted the question’s potentially misleading nature, and suggested that the rigid ‘yes/no’ structure risked limited policymakers in formulating a question which is as clear and straightforward to voters as possible. In their remarks, they said:

The research showed that a few people did not know whether or not the UK is currently a member of the EU and this presented a risk of misunderstanding. However, amending the question to make the UK’s current membership status clear while retaining ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ answers presented difficulties with some element of perceived bias remaining in each version tested.

During the Committee hearing on the Bill in the House of Lords, Lord Armstrong tabled Democratic Audit and the Electoral Commission’s proposed re-wording as amendment to the referendum Bill, arguing the current question is;

…Inappropriate, confusing and potentially misleading. The wording might be appropriate if the United Kingdom was not a member of the Union but was now proposing to apply for membership, or if we had applied for membership and the Government and Parliament wanted to ascertain whether the electorate would support a proposal to join the Union on terms that would have been negotiated with the existing membership.

He also made it clear in his remarks that it was the Electoral Commission’s version of the question that he was adopting as his preferred alternative.

In response to the Electoral Commission’s earlier evidence, Democratic Audit asked a number of experts whether the Electoral Commission and Professor Dunleavy were correct in their diagnosis and prescription. While opinion was divided, most agreed with the argument that the question was misleading, unclear, or both, with Cas Muddie of the University of Georgia arguing:

The Electoral Commission was right to advice against the original question, which was unclear about the current membership status of the United Kingdom. It is also unwise to use a question that leads to the answers “yes and “no,” as survey research has shown that (uninformed) people tend to favour “yes” over “no,” irrespective of the question, simply because they prefer to agree rather ‘than disagree

In the future, we can now hope that future referendums will be more flexible in presenting questions to the electorate, with the Electoral Commission seemingly now willing to move away from the Yes/No format that can provide particularly limiting in presenting a clear choice to the electorate.

Ultimately, the Wharton bill fell because of some well-coordinated rear-guard action by Labour, Liberal Democrat, and some cross-bench peers. While a large element of their plan was to load the Bill with superfluous amendment, Lord Armstrong’s was not in that category. The public are understandably divided as to whether a referendum – or for that matter Britain’s continued membership of the European Union – is a good thing, but we can take some comfort that future referendums are now less likely to be subject to a rigid yes/no formulation that risks confusing voters.

—

Note: please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1cMNHP5

—

Sean Kippin is Managing Editor of Democratic Audit, and is one of two people responsible for DA’s day-to-day management, website, blog and wider output. He has a BA in Politics from the University of Northumbria and an MSc in Political Theory from the LSE. He has worked for MPs Nick Brown and Alex Cunningham, as well as the Smith Institute think tank. He has been at Democratic Audit since June 2013, and can be found on twitter at @se_kip.

Sean Kippin is Managing Editor of Democratic Audit, and is one of two people responsible for DA’s day-to-day management, website, blog and wider output. He has a BA in Politics from the University of Northumbria and an MSc in Political Theory from the LSE. He has worked for MPs Nick Brown and Alex Cunningham, as well as the Smith Institute think tank. He has been at Democratic Audit since June 2013, and can be found on twitter at @se_kip.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Lord Armstrong’s EU Bill Amendment shows the way forward for the framing of referendum questions https://t.co/9CjkDSzhi4