Canada’s 2019 federal election: is the first-past-the-post electoral system broken?

In Canada’s recent federal election, the most popular party by vote share, the Conservative Party, did not gain the most seats in parliament and smaller parties also lost out, to the benefit of Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Party, who will form a minority government. Chris Stafford assesses what this means for the country’s on-going debate on electoral reform.

Justin Trudeau. Picture: Steve Jurvetson/(CC BY 2.0) licence

After a tense election campaign Justin Trudeau and his Liberal Party have narrowly retained power in Canada. Trudeau won a landslide victory in 2015, ousting the unpopular Conservative government led by Stephen Harper on a wave of progressive promises and optimism. Now, just four years later, Trudeau has lost his majority and finds himself at the helm of a minority government.

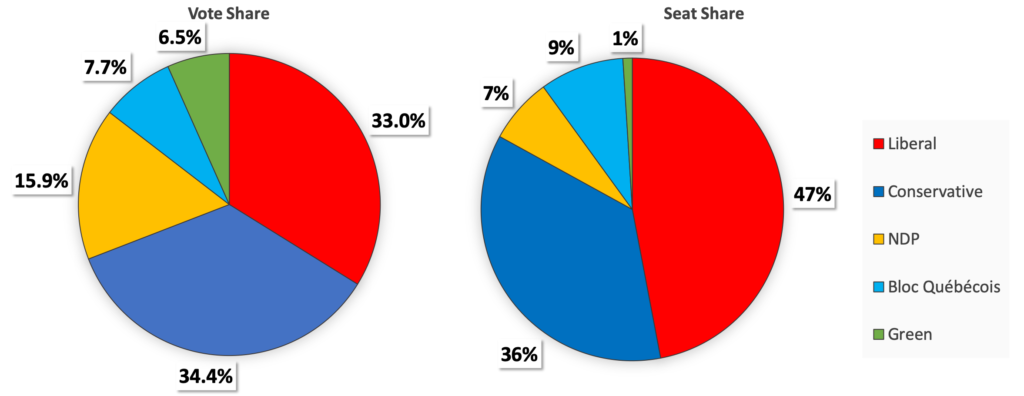

Despite winning the most seats in the Canadian lower house, the Liberal Party did not win the popular vote, coming second to the Conservative Party, who achieved 34.4% to the Liberals’ 33%. Although first-past-the-post electoral systems are well known to facilitate such outcomes, this time it is particularly noteworthy because it was one consequence of the Liberals abandoning a key policy from their 2015 election campaign.

Justin Trudeau had pledged that if his Liberal Party won in 2015 it would be ‘the last federal election conducted under the first-past-the-post voting system’, yet four years later Trudeau has managed to remain in power thanks to the quirks of the electoral system he had once he promised to reform.

Figure 1: 2019 Canadian federal election results: vote share versus seat share

Seats won by party: Liberals 157; Conservative 121; Bloc Québécois 32; NDP 24; Green 3; Independent 1

Trudeau’s commitment to electoral reform was questioned early on in his first term in office, when the party proposed that the membership of the parliamentary committee on electoral reform should be based on seat share in Parliament rather than vote share. This was heavily criticised not only for going against the spirit of reform but also because it gave the Liberal Party the most sway within the group. The pledge to reform the electoral system was eventually dropped, ostensibly because no consensus could be found for an alternative, but many blamed political expediency and as such Trudeau’s progressive reputation took a hit.

Subsequent referendums on moving to a system of proportional representation for regional elections in British Columbia and then in Prince Edward Island did lend some credence to the official explanation, with voters in both regions rejecting proportional representation in favour of sticking with the existing systems. Nonetheless, the issue of electoral form has become symbolic. While for many of the promises Trudeau made in 2015 it is debatable whether he kept them or not, there is no escaping the fact that the party unceremoniously dropped one of its key pledges from its 2015 platform.

While this broken promise proved important during the 2019 campaign, it has gained additional significance following the results. Like many third parties in Westminster parliamentary systems, the left-wing New Democratic Party (NDP) has often been in favour of electoral reform, but this latest election result makes the issue all the more salient for them, since they received a significantly lower percentage of seats than their vote share might warrant in a proportional system (7% of seats for 16% of votes; see Figure 1). Their leader, Jagmeet Singh, was quick to call Canada’s political system broken and call for reform. The Green Party were also heavily penalised by the disproportionality of the current system and would also likely support reform.

This is where Trudeau’s broken promise may come back to haunt him. Holding the largest number of seats, but short of a majority in the House of Commons, the Liberals are going to need the support of these smaller parties if they want to have any hope of passing legislation. With a Liberal-Conservative alliance unlikely, Trudeau will need to get the NDP on side to help him govern; this is something he cannot take for granted even given the traditional animosity between the NDP and the Conservatives.

After abandoning his pledge to reform the electoral system, Trudeau later said that he might consider taking another look at electoral reform if pushed by other parties, although he ruled out a proportional system, saying it would ‘exacerbate small differences in the electorate’. With the NDP potentially holding the balance of power in the new Parliament and electoral reform once again a salient issue, Trudeau may not have much room for manoeuvre.

It remains to be seen what the NDP might demand in exchange for their support, whether it be in a formal coalition or a ‘supply and demand’ arrangement much like the UK Conservatives agreed with the DUP in 2017. However, given the controversial election result, magnified by Trudeau’s broken promise, it seems highly likely that electoral reform will come back onto the agenda in some form or another.

The first-past-the-post system is often criticised for producing exaggerated and increasingly disproportional results in a multi-party system and disadvantaging the views of many voters. Whether proportional systems see more people’s desires acted upon is contested, but there is certainly value in making people feel like their vote counts. Proportional systems have also been shown to foster higher voter turnout and can help minority groups and regional areas to feel more represented. In a country as large and as diverse as Canada, a more proportional system may improve the way democracy functions for many people.

However, despite losing out because of the current system’s disproportionality in this election, it is unlikely the Conservative Party would endorse changing Canada’s electoral system, certainly not along more proportional lines, with the party traditionally opposing reform at national and regional levels. Whether less proportional reforms such as the Alternative Vote system or its variants could appeal to the party given their current situation remains to be seen.

Electoral reform in Canada is therefore once again on the agenda, but there is no guarantee that any meaningful change will happen. Previous regional referendums on electoral reform have seen voters favour the status quo, but the starkly disproportional results of the 2019 federal election may prove to be a key turning point. While the disproportionality of seats to vote share the current system creates is nothing new, the fact that the party that benefited from it this time around had once promised reform, and the way it determined the ‘winning’ party in Parliament, makes the issue that much more salient. Many Canadians may therefore once again find themselves asking if there is a better way to do things.

This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Democratic Audit.

About the author

Chris Stafford is a PhD student at the University of Nottingham, focusing on democracy and representation. His current research investigates how MPs have reacted to the result of the EU membership referendum and how this relates to the opinions of their constituents. He tweets @CJStafford14.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.