Three questions ahead of Northern Ireland’s local elections 2019

Northern Ireland votes in local council elections on Thursday, 2 May. These elections take place while the Northern Ireland Assembly remains dormant, the Brexit process raises seemingly unresolvable questions about the Irish border, and in the aftermath of the murder of journalist Lyra McKee. Jamie Pow previews the elections and outlines some key questions they highlight for Northern Irish politics.

Belfast City Hall. Picture: Macnolete/CC BY 2.0 licence

Local elections on 2 May will carry symbolic and practical significance in Northern Ireland. Since the collapse of the devolved institutions at Stormont over two years ago, local councillors have been the only elected representatives taking public policy decisions on Northern Irish soil. A total of 819 candidates will be competing for 462 seats across 11 council districts. But insofar as any substantive issues receive significant scrutiny and attention from voters in this election, they are unlikely to be issues of local government.

If there is one predictable feature of any election in Northern Ireland – at any level – it is the structural dominance of the ethno-national dimension. Within each ethno-national bloc, voters tend to support the party they perceive to be the strongest at representing the interests of their community. In every election since 2003, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Féin have been the largest unionist and nationalist parties respectively, marginalising the more moderate Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) and Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), and leaving the centrist Alliance Party largely stagnant.

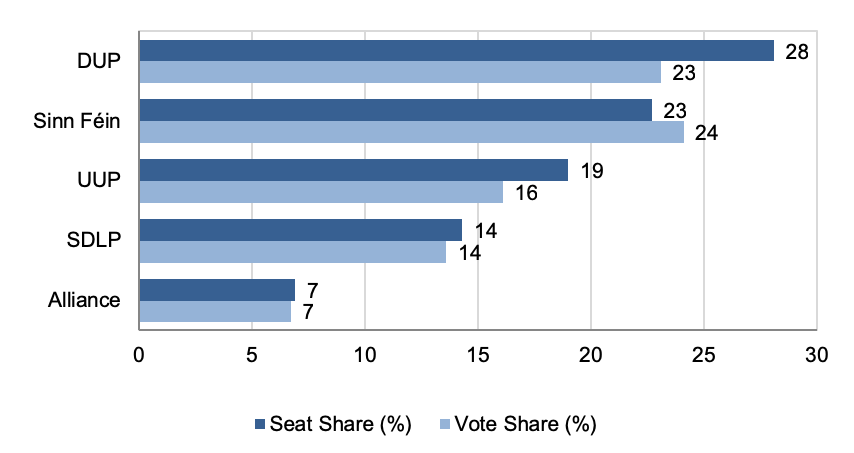

Below we see a summary of the performance of the five main parties in the most recent local elections (in 2014). Barring a major upset, this configuration is unlikely to change much. Still, this will be the first electoral test for the parties in nearly two years. When the votes are counted, three questions will be worth keeping in mind.

Figure 1: Northern Ireland 2014 local election results by party

1. Will there be any Brexit effect?

As in other parts of the UK, Brexit is at the top of the political agenda in Northern Ireland – and it is an issue that reinforces, rather than undercuts, the ethno-national dimension. Nationalists overwhelmingly voted to remain in the EU; a majority of unionists voted for the UK to leave. In other words, the issue of Brexit does not challenge the basis of Northern Ireland’s party system.

However, Brexit has the potential to shape voting behaviour within the unionist bloc in particular. While a clear majority of unionist voters (66 percent) supported Leave in the 2016 referendum, a significant minority (34 percent) did not. The two main unionist parties were divided during the campaign itself: the DUP advocated Leave, but the UUP backed Remain.

Since the referendum, the DUP has supported the UK government’s goal of leaving the customs union and single market, while simultaneously insisting that the Irish border remain frictionless and that Northern Ireland exits the EU on the same basis as the rest of the UK. As the ongoing impasse at Westminster has shown, these goals have so far proved impossible to reconcile.

Having advocated for a different outcome in the first place, the UUP could have credibly challenged the coherence of the DUP’s position, and indeed challenged its confidence and supply agreement with the government, either by championing a soft exit for the whole of the UK or by continuing to advocate remaining in the EU altogether – on the grounds that any other outcome poses a long-term threat to Northern Ireland’s place in the UK. However, the UUP has failed to differentiate itself sufficiently from the DUP’s position, and so is unlikely to tap into unionist voters’ concerns about the potential impact of Brexit on the Union.

2. Will there be much cross-community voting?

Electoral competition is overwhelmingly intra-communal, even in local elections, with little support for unionist parties from nationalist voters – and vice versa. However, a slightly more complicated picture emerges when we consider one of the features of the electoral system. The single transferable vote (STV) is used in both Assembly and council elections (and in the upcoming European Parliament elections) in Northern Ireland. It is a proportional system, typically producing a close relationship between the number of votes received by each party and the number of seats they win (as the figure above shows). But it is also a preferential system, giving voters the opportunity to rank candidates from different parties in the order of their choice (1, 2, 3 etc.). Once first preference votes have been recorded, lower preference votes can be ‘transferred’ to other candidates under a sequential procedure.

In an analysis of transferred votes in the 2017 Assembly election, only a negligible number of voters who gave their first preference vote to either the DUP or Sinn Féin gave a lower preference vote to the other party. However, cross-community transfers were evident among voters giving the UUP, SDLP and Alliance their first preferences. For example, 10% of UUP transfers came from SDLP first preference votes, while most of the SDLP’s transfers (24%) came from UUP votes. With arguably less at stake in local elections, we might expect these patterns to hold, or even grow. However, it is possible that many UUP voters will feel uncomfortable with the SDLP’s recently announced partnership with Fianna Fáil, one of the main parties in the Republic of Ireland. The elections on 2 May will be the first electoral test for this new North–South political alliance, and the first opportunity to see if it has a negative effect on cross-community voting within Northern Ireland.

3. Will voter turnout take a hit?

Across the UK, levels of voter participation tend to be lower in local elections compared to elections for higher levels of government. This pattern holds in Northern Ireland too, but the difference is historically less pronounced. In 2014, turnout in district council elections in England was 37%, compared to 51% in Northern Ireland – only four points lower than turnout in the Assembly election in 2016.

However, it is possible that turnout in the upcoming local elections will be the biggest indicator of change from previous elections. With widespread frustration with the political stalemate at Stormont, combined with an underlying lack of engagement with issues at the local government level, it is likely that many voters will register their protest by simply staying at home on 2 May. The extent to which a sense of apathy and frustration translate into abstention is difficult to predict.

The murder of Lyra McKee by the ‘New IRA’ in Derry on 18 April, exactly two weeks ahead of election day, has added a sobering new dimension to the political discourse. At the funeral of the award-winning journalist, Father Martin Magill commended politicians for their unity in condemning any such violence, but he went on to deliver a striking rebuke: ‘Why in God’s name does it take the death of a 29-year-old woman with her whole life in front of her to get us to this point?’ Before he reached the end of the sentence, the congregation rose to its feet in spontaneous applause; the political leaders at the front eventually followed.

The murder has certainly had an impact on the political mood in Northern Ireland, tapping into an emotive rejection of the status quo. As far as the local elections themselves are concerned, it is unclear how this collective mood will translate into voting behaviour. Indeed, as voters – and parties – increasingly look beyond 2 May, to renewed cross-party talks which are due to re-start the week after them, apathy may yet be the dominant response. Ironically, while these elections form an essential part of the democratic process at the local level, they are simultaneously a distraction from the urgent work of consolidating a fragile peace process.

About the author

Jamie Pow is a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Political Research at KU Leuven. He is the author of the chapter on local government and politics in Northern Ireland in The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit, published by LSE Press.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.