Audit 2017: How well does the UK’s media system sustain democratic politics?

The growth of ‘semi-democracies’ across the world, where elections are held but are rigged by state power-holders, has brought into ever-sharper focus the salience of a country’s media system for the quality of its democracy. Free elections without some form of media diversity and balance clearly cannot hope to deliver effective liberal democracy. As part of our 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Ros Taylor and the Democratic Audit team look at how well the UK’s media system operates to support or damage democratic politics, and to ensure a full and effective representation of citizens’ political views and interests.

Photo: Garry Knight via a CC BY 2.0 licence

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

What does liberal democracy require of a media system?

- The media system should be diverse and pluralistic, including different media types, and operating under varied systems of regulation, designed to foster free competition amongst media sources for audiences and attention, and a strong accountability of media producers to citizens and public opinion.

- Taken as a whole, the regulatory set-up should guard against the distortions of competition introduced by media monopolies or oligopolies (dominance of information/content ‘markets’ by two or three owners or firms), and against any state direction of the media.

- A free press is a key part of media pluralism – that is, privately owned newspapers, with free entry by competitors, and only normal forms of business regulation (those common to any industry) by government and the law.

- Because of network effects, state control of bandwidth, and the salience of TV/ radio for citizens’ political information, a degree of ‘special’ regulation of broadcasters to ensure bipartisan or neutral coverage and balance is desirable, especially in election campaign periods. However, regulation of broadcasters must always be handled at arm’s length from control by politicians or state officials, by an impartial quasi-non-governmental organisation (quango) with a diverse board and professional staffs.

- Where government funds a state broadcasting service (like the BBC) this should also be set up at arm’s length, and with a quango governance structure. Government ministers and top civil servants should carefully avoid forms of intervention which might seem to compromise the state broadcaster’s independence in generating political, public policy or other news and commentary.

- Journalistic professionalism is an important component of a healthy media system, and the internalisation of respect for the public interest and operation of a ‘reputational economy’ within the profession provide important safeguards against excesses, and an incentive for innovation. Systems that strengthen occupational self-regulation within the press are valuable.

- The overall media system should provide citizens with political information, evidence and commentary about public policy choices that is easy to access, at no or low cost. The system should operate as transparently as possible, so that truthful/ factual content predominates, truthful content quickly ‘drives out’ incorrect content, and ‘fake news’, ‘passing off’ and other lapses are minimised and rapidly counter-acted.

- People are entitled to published corrections and other effective redress against any reporting that is unfair, incorrect or invades personal and family privacy. Citizens are entitled to expect that media organisations will respect all laws applying to them, and will not be able to exploit their power to deter investigations or prosecutions by the police or prosecutors.

- Public interest defences should be available to journalists commenting on possible political, state and corporate wrongdoing, and media organisations should enjoy some legal and judicial protection against attempts to harass, intimidate or penalise them by large and powerful corporations, or by the state.

- At election times especially, the media system should inform the electorate accurately about the competing party manifestos and campaigns, and encourage citizens’ democratic participation.

The UK has long maintained one of the best developed systems for media pluralism amongst liberal democracy, centring around:

- A free press, one that is privately owned and regulated only by normal business regulations and civil and criminal law provisions. The biggest UK newspapers are highly national in their readership and coverage. They characteristically adopt strong political alignments to one party or another. A voluntary self-regulation scheme has provided a weak code of conduct and redress in the event of mistakes in reporting or commentary.

- A publically owned broadcaster (the BBC), operated by a quasi-non-governmental agency (quango), at arm’s length from any political control by the state or politicians. It is regulated by another arm’s length quango, Ofcom so as to be politically impartial in its coverage, according space to different parties and viewpoints.

- A few private sector broadcasters whose political coverage is also regulated by the same set of rules to be politically impartial – the rules here are also set and regulation enforced by Ofcom, insulated from control by politicians or the state and from the regulated companies.

- Strongly developed journalistic professionalism, with common standards of reporting accuracy, and much looser agreement on fairness in commentary and respect for privacy, shared across (almost) the whole occupational group. But breaches are enforced only informally by weak social sanctions, such as disapproval or reputational damage for offenders within the profession. And

- Social media that have recently emerged as an increasingly salient aspect of the overall media system, and resemble the free press in being unregulated beyond normal legal provisions. The biggest online sites and associated social media are journalistically produced by newspapers, and generally operate on the same lines, although with less political colouration of news priorities. But much politically relevant content is also generated by a wide range of non-government organisations (NGOs), pressure groups and individuals, many of whom are strongly politically aligned and may not feel bound by journalistic standards. We discuss the role of social media at greater length in a separate chapter of the 2017 Audit.

Recent developments

In recent years the UK’s media landscape has undergone enormous transformation. Not only has news consumption shifted online, but the growth in social media has enabled people to find and share information in ways that challenge the traditional hegemony of state-funded broadcasters and the national press.

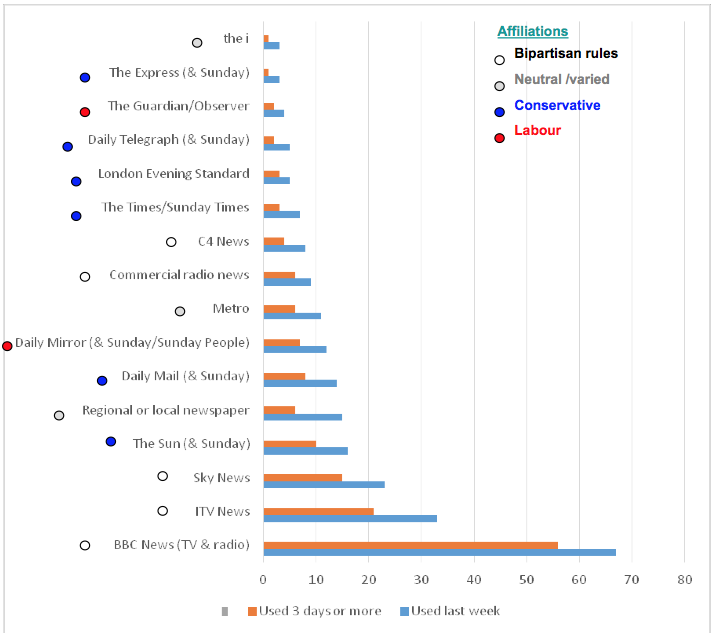

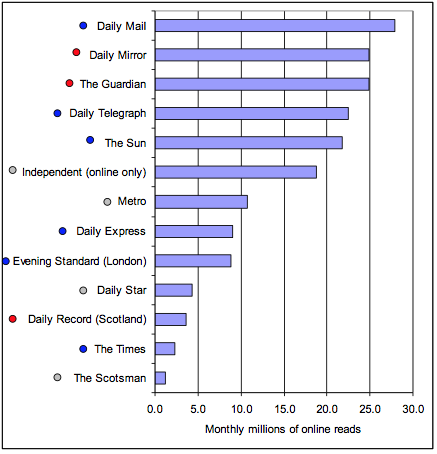

One big source of concern about the democratic qualities of the UK’s media system has been the typically overwhelming predominance in the press of titles backing the Conservative party, with far fewer backing Labour, and only episodic support from smaller papers for the Liberal Democrats. Once predicted to become just another depoliticised operation of conglomerate corporations, in fact newspapers are still run in ‘press baron’ and hands-on fashion by powerful companies or media magnates (like Rupert Murdoch and the Barclay brothers). Chart 1 shows that the anti-Labour and pro-Brexit Sun is by far the biggest newspaper, and Rupert Murdoch also owns the Times/Sunday Times. The Daily Mail, Express and Telegraph complete the Tory press hegemony. The Labour-backing Trinity Group newspapers (the Daily Mirror and Daily Record) have smaller readerships, plus the Guardian. Some papers also take a neutral or more varied political line.

However, Chart 1 also shows that in terms of media exposure by 2017 the non-partisan news media had maintained far more reach and regular use than print newspapers, with a trio of TV news outlets (BBC, ITV and Sky News) plus radio providing much of people’s political information. All broadcasters operate under political neutrality rules that apply with special force during election campaigns and require a bipartisan balancing of Conservative and Labour viewpoints (given their historic dominance of general election voting) plus the broadly proportional representation of other parties – e.g. giving the SNP in Scotland equal prominence.

Chart 1: The percentage of UK respondents who used different TV, radio and print news sources in 2017 – and the political affiliations of these sources

Source: Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017 and the authors

Chart 2: The online monthly readership of UK newspaper websites

Source: UK Press Gazette

In addition, however, newspaper websites now provide major sources of revenue and compete with broadcast and online-only publications to secure online prominence. Chart 2 shows that the picture of papers’ online usage shows a greater balancing of political alignments, with Labour enjoying (in 2015 and 2017) the backing of the Guardian website, which has a much bigger reach than its print version. The Daily Mirror is also prominent. On the Tory side the Daily Mail is the leading online title, along with the Telegraph.

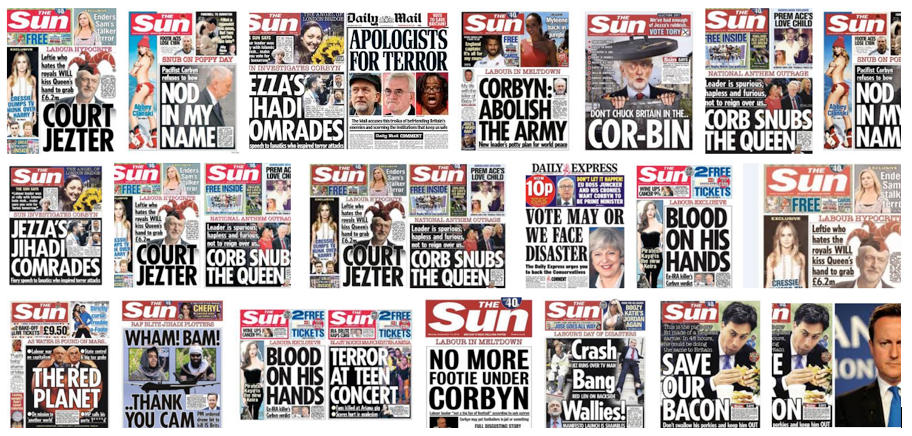

These modifying factors may perhaps have begun to blunt the ‘power of the press’ compared with (say) 1992, when Murdoch’s leading title boasted ‘It was the Sun wot won it’ after the general election. In 2017 the Sun’s election day ‘Cor-Bin’ front page was no less strident in denouncing Jeremy Corbyn. The Daily Mail devoted 15 pages to anti-Corbyn and anti-Labour stories and commentary on the day before polling. Over time the levels of political bias generated can also be striking, as this selection demonstrates:

Yet optimists point out that Corbyn’s Labour surged in popularity during the campaign, and forced a hung Parliament, despite facing a wall of Tory press criticism. Perhaps, then, media diversity is working after all, allowing voters to form their own opinions from a range of different sources?

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Charts 1 and 2 demonstrate that the UK’s media system remains essentially pluralistic, especially in the complementary nature of a free press offset by bipartisan regulated broadcasting. | The print versions of the leading national newspapers remain wedded to highly partisan approaches to covering UK politics and elections. Cross-ownership of titles and broadcasting by powerful and committed corporate leaders actively trying to sway elections and policy decisions (like Murdoch) distorts political power away from political equality. Traditional forms of joint agenda-setting by journalists (e.g. ‘wolf pack’ questioning on top issues) and new developments (e.g. press preview programmes on 24-hour TV and press front pages on broadcaster websites) mean press distortions can drag public service broadcasters into line with a press-led agenda. |

| The growth of satellite and online TV channels, and rapid increases in the numbers of specialised or paid-for TV channels (many catering for niche interests) has reduced the ways in which TV presents a common news agenda to all citizens. Yet the BBC, ITV, Channel 4 and Sky News still compete very effectively for news and politics audiences (Chart 1). Although its audience is aging somewhat, the BBC’s broadcast news coverage continues to reach two-thirds of the public each week. | Press coverage of the 2016 EU referendum campaign was frequently hyper-partisan, disingenuous or actively misleading (as in claims that Turkey was poised to join the EU). If and when such claims were ever corrected at a regulator’s request, this happened only after readers had voted. |

| The mainstream press has experimented with subscription models that offer an alternative to paywalls, such as voluntary subscriptions or one-off donations and crowd-funded journalism. | The public’s reluctance to pay for news, both online and offline, as well as declining advertising revenues and insurgent start-ups represent an existential threat to established media brands. The local press is also in decline, with far fewer reporters. Those who remain are sometimes based outside their ‘beat’ and discouraged from original reporting for reasons of time and cost. |

| Several new versions of self-regulation have emerged since the dissolution of the PCC, with Impress and Ipso offering different models (see below). The closure of the News of the World over its toxic phone hacking culture looms large still in editors’ and journalists’ consciousness. | The newspaper industry has failed to reach consensus on press regulation after the hacking scandal and Leveson report, including on the chilling effect of Section 40 of Courts and Crimes Act (see below). Complaints mechanisms are often weak and unclear, especially among new entrants. |

| The Freedom of Information Act, a key right for citizens that is also a valuable tool for journalists, has survived repeated threats due to Whitehall cost-cutting. | Privacy injunctions are the preserve of the wealthy, although they are now declining in numbers. Ordinary citizens typically find it hard to achieve redress and corrections for mistakes. |

| Parliamentary reporting has adapted to the live blog format, arguably providing a more detailed and real-time account of proceedings than the legacy print media did. | Coverage of Welsh politics is especially inadequate. The nation lacks a powerful home-grown media and the Welsh Assembly has considered appointing its own team of journalists to report proceedings. This, like local authority-run newspapers, is a problematic development. |

| Current opportunities | Current threats |

|---|---|

| Citizens have mobilised on social media to counteract newspaper partisan or commentary excesses – eg Stop Funding Hate’s campaign to shame big advertisers into boycotting newspapers accused of anti-Islam coverage. As online readers grow more salient, so perhaps a somewhat less partisan style of press political journalism may take root. Crowd-funded initiatives like WikiTribune may have the potential to make the ownership and administration of media outlets more transparent and accountable to their readers. | Both ‘alt-left’ and ‘alt-right’ media outlets, run directly by political interest groups seeking to manipulate public debates, have already penetrated the UK market. They often used ‘data-industrial complex’ methods to target sets of swing citizens, and paid-for Facebook and Twitter ‘news’ generation to evade journalistic controls or scrutiny. The alt-left (eg the Canary and Evolve Politics) claimed extensive influence in the 2017 general election, while the alt-right (and possibly Russian intelligence) seems to have swayed the EU referendum campaign towards ‘Leave’. |

| Recognising the dearth of local news reporting, some efforts are being made to fund and train reporters. | Official proposals for a modernised Espionage Act threaten whistleblowers and would introduce a further chilling effect to journalists’ ability to pursue stories relating to the ‘secret state’. |

| Libel cases have fallen since the Defamation Act 2013 simplified the public interest defence. If the trend is maintained, this may enable more adventurous investigatory reporting in future. | Mainstream media and journalists are increasingly distrusted by the public, particularly on the left, for their perceived biases and remoteness from ‘ordinary people’. |

| Hyperlocal news models continue to evolve, with the ease of making micro-payments offering the possibility of an (albeit unpredictable) revenue stream (see our social media chapter). | The declining sales of local newspapers, and the closure of many titles, plus the relative weakness of regional and local broadcasting within the BBC and ITV, have all meant that journalistic coverage of local politics has drastically fallen away. Court reporting is also in steep decline. |

The BBC, Channel 4 and Sky

The regulated broadcasters (and in the BBC’s case, state-funded too) have been a key part of the UK’s media system since the BBC was first set up in the 1920s. Their role enjoys a wide amount of cross-party consensus, but the Tory press has constantly accused the BBC of having a ‘left-wing’ bias; conversely, since Jeremy Corbyn became Labour leader, some ‘alt-left’ outlets have attacked the BBC (and in particular its political editor, Laura Kuenssberg) of bias against him. Ofcom is now the BBC’s new external regulator, putting it on a par with other regulated broadcasters, instead of the previous ecceptional situation of the BBC Trust being judge and jury on major complaints. The BBC’s once very extensive online presence has also been cut back to focus on news and programme-specific sites, chiefly as a result of commercial rivals complaining to Ofcom that it was ‘crowding out’ their own web operations.

A Conservative government green paper in 2015 raised the possibility of cutting or reforming the BBC’s licence fee (a disliked tax on TVs) and cutting back the corporation’s remit to focus on news. However, the charter renewal of January 2017 guaranteed the licence fee’s survival for at least 11 years, with inflation-linked increases until early 2022. A new BBC Board– no more than half of whose members are government appointees – was put in place to manage the Corporation. The National Audit Office will now play a role in scrutinising BBC spending.

The BBC also undertook to serve ethnic minority and regional audiences better. The BBC Trust previously found audiences in the devolved regions felt the corporation needed to do more to hold their politicians to account, particularly in Wales, where Cardiff University’s 2016 Welsh Election Study identified a ‘democratic deficit’ in media. As in the English regions, the reach of BBC services is falling as its radio and TV audience ages.

The Brexit referendum campaign represented a major challenge for all the UK media, but particularly so for the BBC’s public service remit and due impartiality. The subject matter was complex and the public was poorly informed about the history and functions of the EU. The Corporation drew up a set of Referendum Guidelines in order to give ‘due weight and prominence to all the main strands of argument and to all the main parties.’ This was characterised as a ‘wagon wheel’ rather than an overly simplistic ‘seesaw’ approach to ensuring impartiality – the latter critiqued by Jay Rosen as ‘views from nowhere’. Despite these efforts, the BBC was criticised for inadequate scrutiny of campaign claims on both sides and faced particular opprobrium from Leave-supporting politicians and newspapers.

At the height of the News of the World phone hacking scandal, the Murdoch-run 21st Century Fox (the ultimate owner of the Sun and the NoTW) withdrew a bid to assume full control of Sky that had previously seemed likely to succeed. After an interregnum, the bid has been renewed and Ofcom has to decide if Fox can meet a key test to take full control of Sky, in which it currently holds a 39% stake: Is Fox run by ‘fit and proper persons’? James Murdoch, who was criticised by Ofcom over his role in the NoTW phone-hacking scandal, is both chairman of Sky and chief executive of Fox.

Meanwhile, the 2017 Conservative manifesto indicated that the other regulated broadcaster, Channel 4, would remain publicly owned and move out of London. But the government’s failure to secure a working majority and Channel 4’s opposition to such a move make this uncertain.

Newspaper closures and online paywalls

For the health of the ‘free press’ in the UK, the ability to run newspaper titles successfully is obviously crucial. With sales and advertising revenue falling, the Independent newspaper closed its weekday and Sunday editions in 2016 ‘to embrace a wholly digital future’, and subsequently reported a return to profit. The Times and Financial Times continued to maintain online paywalls to fund their journalism, with the Telegraph also erecting a partial paywall. The London Evening Standard became a free paper in 2009, maintaining its circulation. However, only 3% of Britons have an online news subscription, one of the lowest percentages across the European Union. At Murdoch’s insistence, The Sun experimented with a paywall in 2013, but abandoned it two years later as its online readership numbers fell. A majority of readers seem unwilling to pay for online news when it is freely available elsewhere. However, the Guardian reports 230,000 members who pay at least £5 a month, and 190,000 one-off contributors, both on a voluntary basis.

Regional papers in big cities outside London, and local publications across the country also experienced a drop of 12% in both digital and print revenues in 2015-16. Across the UK 198 local papers closed in 2005-16. The decline in advertising revenues is the principal driver of the ongoing decline in local journalism, but not the only one. More people are renting privately and moving between local areas, and the sociologist Anthony Giddens has argued that social life has become ‘dis-embedded’ from the local level, so that ‘we can no longer take the existence of local journalism for granted’. The decline in local reporting was exemplified in tragic fashion by the failure of west London’s press to pick up on the repeatedly expressed concerns of the Grenfell Tower residents on the Grenfell Action Group blog about the safety of their building, before it burnt down, killing at least 80 people in June 2017.

Some efforts are being made to reinvigorate the sector. The BBC has earmarked £8m for ‘local democracy reporters’ from selected news services, giving them training and access to BBC video and audio. In addition, the local press decline has been a key catalyst for a growth of citizen-driven hyperlocal sites (discussed in our social media chapter).

Media ownership, partisanship and transparency

A diversity of media ownership has historically been seen as important because of the strong political orientation of the national newspaper titles. But in addition, newspapers provide an important platform for different capitalist interests to campaign for their own interests in regulatory matters and other public policy interests, especially where press titles and broadcast channels are owned by the same mogul or firm.

Ownership of the major newspapers has long been divided among a few large companies, with the American-owned News Corp, publisher of the Sun and the Times, the dominant player. These, along with the Daily Mail (DMG Media), the Daily Express and the Telegraph Media Group, continue to dominate right-leaning coverage, while the Mirror, the Guardian and the Independent occupy the left or centre. Pearson sold the Financial Times to the Japanese company Nikkei in 2015. A Saudi investor, Sultan Muhammad Abuljadayel, took a stake of between 25% and 50% in the Independent’s holding company in 2017, causing concern among some of its journalists, although they were assured its editorial independence would remain intact.

However, online media has inflicted considerable disruption to the newspaper-dominated press model. Digital entrants have used social media to disseminate free news and opinion. Some originate in the US (BuzzFeed, the Huffington Post, Vice), others are funded by the Russian state (Russia Today and the Edinburgh-based Sputnik), while a number of hyper-partisan low-cost start-ups – such as Evolve Politics and the Canary, a free-to-access site funded by advertising and voluntary subscriptions – have generated their traffic via Facebook. These last, which backed the Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn unreservedly, enjoyed particular success during the 2017 General Election campaign. Their online reach among younger voters during that campaign may have exceeded that of the established mainstream press.

The plethora of new entrants – which, while overwhelmingly digital, include the free Metro and small-scale print publications such as the anti-Brexit weekly the New European (owned by Archant Media) – means UK media is more pluralistic than ever before. These new entrants, however, are not always transparent about their ownership and do not always choose to join a regulator. For example, Sputnik News’ About Us page makes no mention of its control and ownership. Neither Sputnik nor Breitbart provide any channel for readers to make a complaint about their reporting, apart from an online contact form on the Sputnik page, and neither are members of a press regulation body. Social media presents a new set of challenges to democratic debate, which will be explored in more detail in the next chapter.

Journalists have been gloomy about the decline of paid-for news contents and its adverse implications for the health of media outlets and the ability of the press to report freely. Freedom House identified ‘varied ways in which pressure can be placed on the flow of objective information and the ability of platforms to operate freely and without fear of repercussions’. They rated the UK’s media environment as ‘free’ in 2017, giving it an overall score of 25 (where 0 denotes the most free and 100 the least). This represents a four-point worsening in the UK’s score since 2013. Although Freedom House considers the UK’s press ‘largely open’, significant concerns about regulation and government surveillance are unresolved.

Press regulation and the Crime and Courts Act

If the press or other media behave badly, they have the capacity to generate a great deal of misery for the subjects of poor or inaccurate reporting. UK newspapers maintained for many years a very weak apparatus of ‘self-regulation’, which collapsed in the wake of a major scandal about reporters at the News of the World, Daily Mirror and other tabloid titles ‘hacking’ the phones of celebrities and politicians so as to uncover aspects of their private lives. This was always a criminal activity, but Scotland Year proved strangely reluctant to act until long after the large scale of scandal became apparent.

Our previous 2012 Democratic Audit was published just before Lord Leveson produced his long-awaited Inquiry into the Culture, Practices and Ethics of the Press dealing with phone-hacking and press intrusion. This called for an independent, self-regulatory body to create and uphold a new standards code for the media. Leveson deemed the previous Press Complaints Commission ‘not fit for purpose’ and it was dissolved. Many of Leveson’s criticisms echoed those raised by the 2012 Audit.

At the time of writing, the industry has been unable to agree on a common self-regulatory body. The only one to have gained approval from the government-created (but independently-appointed) Press Recognition Panel (PRP) is Impress, which regulates 40 small, chiefly local publications. Most national newspapers have joined the Independent Press Standards Organisation (Ipso). However, the Financial Times and the Guardian chose to set up their own internal mechanisms for handling complaints, citing worries about Ipso’s independence and the royal charter model that underpins it. The charter is not a statute but is drafted and approved by the Privy Council, which its critics argue amounts to ‘unacceptable political involvement’ in press regulation.

In an effort to encourage publishers to join a PRP-approved regulator, section 40 of the Crime and Courts Act 2013 gives those that have done so the opportunity to settle libel action through a low-cost arbitration scheme. If they do not, they may be liable for the claimant’s costs in libel, privacy or harassment cases. The vast majority of the press have vociferously opposed the implementation of section 40, with the FT opening its objections by claiming that the press landscape had been ‘utterly transformed’ since the publication of the Leveson report. Index on Censorship warned that section 40 ‘protects the rich and powerful and is a gift to the corrupt and conniving to silence investigative journalists – particularly media outfits that don’t have very deep pockets’. The 2017 Conservative Party manifesto promised to repeal section 40, which clearly has not worked (and which would cause the PRP to close). But it also said that the promised second stage of the Leveson inquiry will not go ahead – leaving considerable uncertainty about the shape, let alone the effectiveness, of any future press regulation or self-regulation.

Libel law

For decades the English law of libel has provided for potentially large damages against anyone publishing statements likely to lower the reputation of the claimant in the eyes of reasonable people, even if the statements were true. Papers also had to prove that ‘defamatory’ statements were not maliciously motivated. The Defamation Act 2013 simplified the so-called ‘Reynolds defence’ against libel by codifying it more simply: if a statement is in the public interest and the writer reasonably believes it to be so, it enjoys protection. In addition, a libel claimant must prove the statement caused ‘serious’ harm. English PEN and Index on Censorship both welcomed the overhaul: ‘England’s notorious libel laws [have been] changed in favour of free speech’, said the latter. The number of defamation cases fell to 63 in 2014-15, the lowest for six years. A growing proportion of these related to social media postings by private individuals.

English law also allows for ‘gag’ injunctions preventing publication of details (like names) to be sought if the subject can claim their privacy would be damaged. The media monitoring organisation Inforrm recorded only four privacy injunctions against the media in 2015. Their decline appears to be linked to the difficulty of stopping information from being published by third parties online and the risk of court proceedings being made public, thus undermining the very purpose of the action. The privacy injunction remains a tool of the rich: ‘With average legal fees of £400 an hour, the first court hearing would cost up to £100,000,’ reported the Guardian in 2016. For the overwhelming majority of citizens, pre-emptive action against breaches of privacy is out of the question and post-hoc privacy actions likewise impossible. Self-regulation and effective means of redress therefore take on an even greater importance.

The proposed Espionage Act

The UK government operates a system (called D notices) where they can exceptionally bar papers or broadcasters from running items that would endanger a clear national interest (e.g. publishing the names of UK espionage agents). UK journalists have been vigilant in keeping such cases to an absolute minimum. However, other developments have changed the picture a lot.

In 2013, the American IT contractor Edward Snowden passed large amounts of classified National Security Agency material to the Guardian and Washington Post which revealed details of government surveillance programmes. The Guardian possessed a copy of some of the leaked material. GCHQ requested the files, which the paper did not hand over. Warned that the security services were considering taking legal action to halt its reporting, the Guardian destroyed the hard drives and memory chips with cutting tools at their offices. This was ‘a largely symbolic act’ the paper said, because the same files were stored in other jurisdictions.

Given the relative ease of disclosing large amounts of sensitive information in the digital era, the Law Commission has since undertaken a review of the Official Secrets Act which recommends replacing it with an Espionage Act. For the first time, the proposed Act would criminalise receiving and handling data that the government deems damaging to national security, thereby drawing into its ambit editors and journalists who are merely examining leaked material. Under the proposals, prosecutors would only have to prove that it ‘might’ damage national interests, rather than the current test that it was ‘likely’ to do so. The Commission also suggested increasing the maximum prison term from two years, noting the penalty in Canada is up to 14 years. It would also become possible to prosecute non-Britons.

The Commission agreed with Lord Leveson in his inquiry that introducing a statutory public interest defence specifically for journalists was unnecessary. Leveson had concluded: ‘A press considering itself to be above the law would be a profoundly anti-democratic press, arrogating to itself powers and immunities from accountability which would be incompatible with a free society more generally.’

As they stand, the Law Commission’s proposals would exert a chilling effect on both whistleblowers and journalists in receipt of leaked data, let alone editors who took the decision to publish it. The Open Rights Group described the new provisions as a ‘full-frontal attack on journalism… The intention is to stop the public from ever knowing that any secret agency has ever broken the law’.

Re-establishing trust

While trust in the BBC’s ability to deliver accurate and reliable news remains high (70%), trust in journalists in the UK overall remains much lower than in much of the EU and USA. It is lower still among under-35s and those who describe themselves as left-wing. Among journalists themselves, most say owners, advertising and profit considerations have little influence over their work. A quarter of them believe that it is sometimes justifiable to publish unverified information.

However, fact-checking has become an increasingly common practice online, pioneered by the charity FullFact, and later adopted by the BBC, Channel 4 and Guardian. Google’s Digital News Initiative is currently looking at ways to automate parts of the process. Mindful of how Donald Trump’s presidency came about and has developed, the media industry is beginning to grapple with the question of how to report untrue or contested statements made by top politicians.

Conclusions

The media system is changing fast, and it is often easy to lament all change as a decline from a past golden age, and to resent ‘new goods’ that are having disruptive effects. Optimists, on the other hand, argue that the choice and variety of media available to Britons have never been greater and that press and broadcasters are free from censorship or direct government interference.

Pessimists see a largely unreconstructed national press, wedded to truth-bending, high intensity partisanship; with a lot of unregulated power concentrated by a handful of press barons; and a wider profession still resistant to any meaningful professionalism or effective self-policing of journalistic practices. And in the wings, government and official sources are almost constantly proposing restrictive laws that would greatly inhibit journalistic enterprise and ability to investigate – especially where the UK’s still-large ‘secret state’ operates, largely immune to any public or parliamentary scrutiny.

This post does not represent the views of the LSE.

Ros Taylor (@rosamundmtaylor) is editor of Democratic Audit and co-editor of LSE Brexit. She is a former Guardian journalist and has also worked for the BBC.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Democratic Audit article provides a broad assessment of the UK’s media environment. It is generally positive about the […]