Fewer Special Advisers run for Parliament than is generally thought, but those that do are quick to climb the ladder

Special Advisers becoming Members of Parliament is a phenomenon seen as symptomatic of a wider ‘professionalisation’ of British politics. Looking at the career progress of those Special Advisers who served between 1979 and 2010, Max Goplerud shows that they do not all seek a berth in Parliament, though those that do tend to experience rapid career progression.

The notion that Special Advisers (“spads”) turned-MPs dominate the Government and Opposition frontbenches appears periodically in the media as exemplifying the rise of ‘career politicians’ and the ‘professionalisation of politics’. A forthcoming book on Special Advisers by Ben Yong and Robert Hazell of the Constitution Unit explores the profession from 1979 to the present government and provides a detailed look into who they are, what they do, and their relationships and interactions with other actors in the political system.

My recent article for Parliamentary Affairs explores the ‘myth’ outlined above: Is it actually the case that Special Advisers invariably go into politics and rise to the top? The answer, in short, is no. Those Special Advisers who do run for Parliament are not particularly representative of the wider profession.

Despite the presence of some high profile MPs who were previously Special Advisers (most prominently David Cameron and Ed Miliband), the reality is less straightforward. While it is clear that the Special Advisers who do run for Parliament are generally successful (both in terms of their electoral success and subsequently in being promoted), they are not representative of the wider “spad” group. A more satisfactory explanation is that underlying factors drive a certain type of ambitious, politically minded individual to both become a Special Adviser and stand for Parliament. Those individuals are then in a strong position to draw upon the skills and connections they amassed during their time in Whitehall to further advance their political careers.

Special Advisers as Candidates

In total, around 25% of Conservative (1979-1997) and 10% of Labour (1997-2010) Special Advisers ran for Parliament at some point, with most of them doing so after leaving Whitehall. Whilst high compared to the proportion of other groups in the population, it is not so high in absolute terms. These individuals are somewhat younger than the ‘normal’ Special Adviser, with around 40% of those standing for Parliament aged under 30 on their appointment as a special adviser. Conversely, only 25% of ‘ordinary’ Special Advisers are that young.

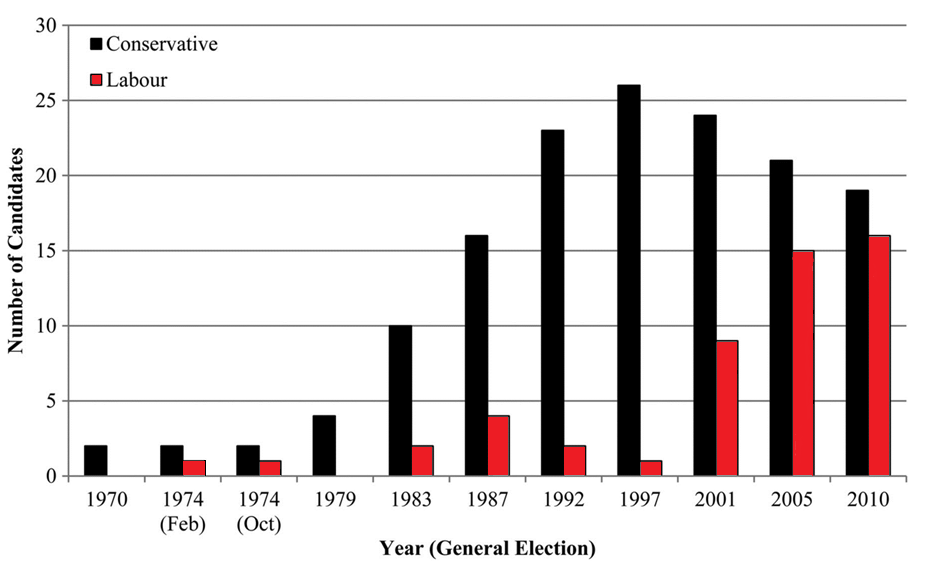

Figure 1: Number of special adviser candidates by general election.

This difference might be uninteresting if these ex-Special Advisers took a number of tries to get into Parliament or contested unwinnable seats. However, that is resoundingly not the case; 80% of “spads” (46 individuals) who stood after leaving Whitehall became MPs at some point. For Labour, 18 out of the 21 former Special Advisers who stood for Parliament have won every General Election they contested.

Special Advisers as MPs

Of those Special Advisers-turned-MPs, nearly half have achieved high office as a Secretary of State (or Shadow Secretary of State) at some point in their parliamentary career, with a full 80% achieving the rank of at least Minister of State. This is very different compared to the great mass of MPs who generally remain on the backbenches.

Special Advisers who become MPs tend to skip the established ‘career ladder’ and head straight to the frontbenches; many become Ministers of State without having first served as a Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) or other comparable junior role. They also tend to be very young upon entering government. The data suggest that 17 ex-Special Advisers became (Shadow) Minister of State before their 40th birthday. Compare this to the median parliamentary candidate who is still attempting to be elected to Parliament at that age. This is also not only a Labour phenomenon—rapid promotion of Special Advisers also occurred under Conservative governments. For at least the last thirty years, Special Advisers-turned-MPs have experienced ‘super-charged’ careers in Parliament, outstripping even other types of ‘career politicians’.

On balance, there is clearly some credibility to the dominant narrative about Special Advisers becoming ministers insofar as those who have ministerial office as their goal seem to be quite successful at achieving it. The evidence suggests that having been a Special Adviser is a good signal that an individual is;

- loyal to the party, and

- has valuable prior experience with how government works.

Key actors, particularly selection bodies for parliamentary candidates and the party leadership (who may well be their former boss!) may see this as desirable and therefore push for these ex-Special Advisers to be placed in safe seats and promoted rapidly.

Yet, we should be careful to distinguish between those Special Advisers who do run for Parliament from those who do not. It is possible to be critical of the advancement of the first group whilst making a different evaluation about the desirability of the profession of “spads” more broadly. If one thinks this rapid promotion is normatively undesirable, it is a problem for the political parties to solve rather than an issue with Special Advisers writ large.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author. It is based upon an article for Parliamentary Affairs which can be found here. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1frMuPI

—

Max Goplerud is a student in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford (Nuffield College) and a contributor to Parliamentary Affairs. He has previously worked at UCL’s Constitution Unit.

Max Goplerud is a student in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford (Nuffield College) and a contributor to Parliamentary Affairs. He has previously worked at UCL’s Constitution Unit.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

How many Special Advisers really become MPs? Max Goplerud has the answer https://t.co/m6kS9XU1JT

Fewer Special Advisers run for parliament than you may think – but those that do rise faster https://t.co/hRNWrpyWom https://t.co/3fE3ffrGRo

A chart from today’s DA article shows Special Advisers as candidates by General Election https://t.co/uZs1mnFHMd https://t.co/DJY0AqrNrg

.@democraticaudit analysis on myth that Parliament is dominated by ex Special Advisers https://t.co/O7iN8BMsDL

RT @PJDunleavy: Fewer Special Advisers run for Parliament than is generally thought, but those that do are quick to climb the ladder http:/…

So it’s not so much about SPADS becoming MP’s, its about their leapfrogging into Govt. Good interpretation here https://t.co/3V4csrky6A

Fewer Special Advisers run for Parliament than is generally thought, but those that do are quick to climb the ladder https://t.co/TfSCtBVkWI

Fewer SpAds run for Parliament than is generally thought, but those that do are quick to climb the ladder https://t.co/2MyCw09elE

Fewer Special Advisers run for Parliament than is generally thought, but those that do are quick to climb the ladder https://t.co/fA9liYRUhS