UK voters see divided political parties as less able to make sensible or coherent policies

It is often said that ‘divided parties lose elections’, with the experience of the Conservatives in the 1990s cited as supporting evidence. But is this the case? Looking at evidence from the British Election Survey (BES), Zachary D. Greene argues that perceptions of party disunity does indeed play a role in how voters assess the competence of parties.

Party members often disagree with their leadership. For example, Conservative MPs rebelled against the leaders’ position in the House of Commons on a vote to send military support to Syrian rebels in 2013. Disagreement is a persistent phenomenon. Under the Labour government in 2006, MPs dramatically rebelled on the Education and Inspections Bill. In the United States, many Democrats distanced themselves from President Obama’s health care reforms. In 2013, German MPs from the Christian Democratic Union roundly criticized then Labour Minister for proposals to reform the pension system.

In response to government disagreement, opposition parties and the media often paint a picture of fractured parties. Cameron “[was dealt] an unprecedented blow”. To pass health care reforms Democratic Party leaders gave away substantial concessions to moderate democrats, yet still lost the support of 34 representatives. The opposition highlighted that Minister von der Leyen’s proposal was described as “wrong” and that other options would be more “honest” by members of her own party.

Despite prominent examples, political science has only just begun to explore the consequences of this behaviour. Traditional theories propose motives for party members to diverge from electoral incentives. From this perspective, in countries with election rules that encourage candidates to cultivate a personal reputation, such as single member districts in the UK or the United States, individual MPs face strong incentives to deviate from the party’s line (see for example this 1995 article by John Carey and Matthew Soberg Shugart. By focusing on the individual’s incentive to deviate, this research often overlooks the potential harm public disagreements might pose for the party’s reputation.

Some research explains the politics within parties. Parties are organizations with diverse memberships that broadly hope to collectively control office. The general nature of this goal provides ample opportunities and incentives for disagreement over even relatively simple aspects of the party’s policy or strategy. Furthermore, competing factions and activists often seek to draw the party leadership in opposing directions.

Diversity of opinion within parties does not assure that the public is aware of these divisions. Serious disagreements only surface under rare circumstances in parliamentary systems. For example, government bills rarely fail parliamentary votes when the cabinet holds a majority. Parties negotiate disagreements informally at party meetings, outside of the public’s eye. A veneer of ideological unity gives the appearance that parties are fully ideologically coherent organizations.

Party leaders actively cultivate an appearance of unity. They demand that members stick to the party’s stated position. In parliament, leaders can use procedures to manipulate the voting order (such as the ‘guillotine’ procedure in the House of Commons) or the parliamentary whip to encourage this discipline. Leaders reward those with positions that closely adhere to their own. Major disagreements when they appear are therefore quite surprising and likely hold implications for how individuals perceive parties’ policy-making ability.

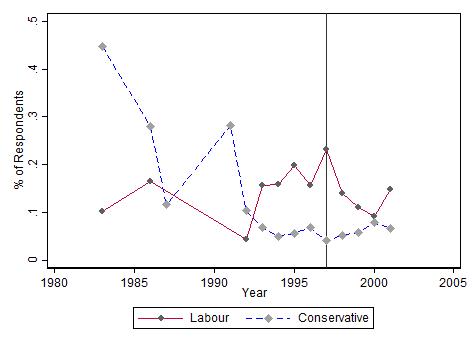

To explore the extent of these implications, I examine survey evidence from the British Election Study (BES) asking whether respondents perceive parties as united or divided. In Britain, perceptions of internal divisions vary dramatically over time. Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of respondents that perceive the Conservative and Labour parties as divided. In the early 1980s, more respondents rated the Conservative government as divided than Labour. A number of factors likely contributed to this impression. For example, prominent members of the Conservative Party criticized positions taken by Thatcher following her ascension to the party leadership. This trend reverses in the mid-1990s only a few years before Labour took office; this trend mirrors the rise of New Labour (ideally, we would see if this reversed again following the start of the Conservative led governing in 2010, but the BES stopped asking questions about government division in 2005.)

There is a clear relationship between parties’ position in government or opposition and perceptions of division. This trend reflects the incentives government parties have to respond to changing world events. To appear responsible, they are forced to respond issues they would normally seek to avoid. Parties in the opposition have the luxury of picking and choosing their battles. Perceptions of governing parties also change over time likely reflecting the effectiveness of the parties’ responses to changes in the economic context.

Figure 1: Perceptions of party division from the British Election Survey

These fluctuations highlight the extent to which voters perceive British parties as divided, but it is unclear if these views matter for opinions of parties’ governing competence or likelihood of voting for a party. When a party publicly divides, as did the Conservatives over Syria, it is often suggested that these disagreements embarrass the parties’ leadership because the party is incapable of articulating a common, agreed upon policy on an issue. The logic follows that it is hard to consider a party a competent executer of policy on an issue when members cannot form a consensus position. Extending this approach, I add that upon perceiving parties as internally divided, voters respond by downgrading their perceptions of parties’ policy competence.

I study the extent to which this logic explains the way people evaluate parties by using voter perceptions of division over time to predict their evaluations of parties’ policy competencies using multivariate regression. I propose that if respondents perceive a party as more internally divided they will rate that party as competent policy-makers on a smaller number of policy areas. The results from this analysis reveal insights into the ways individuals form their opinions of parties’ policy-making ability, an important predictor of individuals’ vote choice.

I find that voters’ respond in inconsistently to observing disunity. Individuals respond to new information based on their pre-established beliefs. The analysis finds that individuals identifying themselves with a party may actually reward a party for greater disunity. Likewise, voters which consider themselves ideologically close to a party may use a cue such as public disagreement to establish whether a party will be capable of following through with their statements.

The evidence indicates a dynamic in which respondents without a partisan attachment are more apt to use their perceptions of disagreement to update their perceptions of the party’s policy competencies. Evidence from Germany adds that ideologically close respondents (without a partisan attachment), rely more heavily on these perceptions, although the evidence from the UK is less straightforward. More broadly, I find that the effect of perceived disunity is not only short-term, but also builds up over time as perceptions of disunity from past years contribute to predicting current assessments of parties’ abilities.

This evidence lends support to a story in which voters use information about parties’ internal politics to understand parties’ policy-making ability. This is good news broadly for conceptions of democratic accountability. Voters form perceptions of parties’ policy-making abilities from observing failures in parties’ internal bargaining. Disagreement likely provides a useful shortcut for voters with limited information and time to research the details of party policy preferences.

These perceptions are enduring and thus likely provide a mechanism through which parties form long term associations with a topic. This evidence provides somewhat less optimistic support for the current Conservative Party. Faced with multiple salient public disagreements, the Conservative Party’s policy-making reputation may languish as only strong party supporters pardon the party for their internal disunity.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Zachary D. Greene is a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Mannheim. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Iowa. His research explores the causes and consequences of intra-party politics for the functioning of democratic politics and accountability. His research can be found in multiple international journals focused on elections, political parties, party politics and government behaviour. For information on his ongoing projects visit his website at zacgreene.com.

Zachary D. Greene is a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Mannheim. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Iowa. His research explores the causes and consequences of intra-party politics for the functioning of democratic politics and accountability. His research can be found in multiple international journals focused on elections, political parties, party politics and government behaviour. For information on his ongoing projects visit his website at zacgreene.com.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Voter perceptions of party disunity inform views on their policy-making ability https://t.co/NXuDwvPe8V https://t.co/pUL8ofMdPD

UK voters see divided political parties as less able to make sensible or coherent policies https://t.co/sLn1WqnlhH

Voter perceptions of party disunity inform views on their policy-making ability https://t.co/rAtY5FAyQS