A close inspection of the British Social Attitudes Survey shows that racial prejudice is in long-term decline

The recent release of the 2013 British Social Attitudes report has triggered the usual bout of agonised soul searching about the state of the nation, writes Robert Ford. But despite much talk of the rise of far-right sentiment in the UK, a comprehensive dig into the data shows that in actual fact racial prejudice is on the decline.

Credit: Mike_fleming, CC BY SA 2.0

The British, it seems, are becoming meaner and more inward looking: less willing to help the poor, more suspicious of immigrants and narrow in their interpretation of who counts as “truly British”.

Yet hidden away in the latest dataset from the British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey, and much less reported, was new information suggesting the continuation of a remarkable trend: the long run decline of British racial prejudice.

From 1983 until 1996, the British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey asked British people what their reaction would be if a close relative were to marry someone who was black or Asian.

This is known in the academic jargon as “social distance” and is a common way to measure prejudice – people who express discomfort about potential in-laws from a different ethnic group clearly have some negative feelings towards this group.

The levels of such prejudice were very high in 1980s Britain: more than half of those surveyed in the early years of the BSA expressed at least a little discomfort about ethnic inter-marriage within their families.

Put another way, any black or Asian person going to meet their partner’s parents for the first time in the 1980s had a better than evens chance of encountering some initial hostility. Such prejudice was an unfortunate part of mainstream attitudes, and hence everyday life, in the Britain of just 30 years ago.

However, in the 1990s things began to change, something I first documented in an article in 2008. Levels of opposition to both black and Asian in-laws started to decline steeply, falling from over 50% in 1989 to around 35% in 1996. A shift towards a more tolerant society seemed to be underway.

What is more, as my analysis demonstrated, the shift was likely to have momentum because it was driven primarily by two powerful long term social trends: generational shifts in attitudes and rising education levels.

Younger cohorts of Britons who had grown up after mass migration began in the 1950s regard diversity as normal, and as a result they were less hostile to ethnic minorities. Those who attend university felt likewise.

As the cohorts who grew up before migration began gradually died off and were replaced by new cohorts who were both much more likely to attend university and much more likely to accept diversity as a normal part of everyday social life, I argued, the inexorable trend would be towards a more tolerant and inclusive Britain.

Until now, I have been unable to test this argument, as the British Social Attitudes discontinued the racial inter-marriage items in 1997, just as the shift in attitudes seemed to be gathering momentum.

What happened next? While my paper noted there were good reasons to expect a continued shift to tolerance and inclusion, there have also been powerful forces operating in the opposite direction since the data ceased.

Immigration to Britain has increased very sharply, and debates over the integration of new migrants, and their impact on national culture, have risen to the top of the agenda.

The terrorist atrocities of 9/11 and 7/7 have created a new climate of fear and suspicion of Muslim Britons, whose commitment to the nation and its values are now questioned. Perhaps these new pressures and anxieties have offset the tides of generational change, or socialised a new generation of voters into suspicion of minorities? In 2013, we finally acquired the data needed to find out.

Figure 1 plots the overall trend in attitudes over thirty years. The continued steady decline in prejudice I predicted in 2008 is borne out in the data: less than one in four white respondents expressed discomfort at the prospect of a black or Asian in-law in 2013, a fall of ten percentage points on 1996, the last time these questions were asked. Despite intense political conflicts over immigration levels and the integration of minorities, the steady decline of British racial prejudice continues.

Figure 1: Share of respondents saying they would mind “a little” or “a lot” if a close relative married someone from a different ethnic group

Source: British Social Attitudes 1983-2013. My thanks to Ingrid Storm for assistance in compiling and charting the figures

One major reason why racism continues its steady decline is that decline is driven by generational replacement, the slow but inexorable process whereby older cohorts of citizens die off and are replaced by new cohorts whose values reflect the very different times in which they grow up.

It is easy to forget that mass immigration is still a recent development in Britain, within the living memories of many voters. A voter drawing her pension for the first time this year would have turned 18 in 1967, a time – one year before Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech – when immigrant minorities were a new and contentious phenomenon and the British born ethnic minority population was small and politically invisible.

Voters turning 18 today have grown up in a vastly different society, where ethnic diversity is an established fact of life in most walks of life, and where one in five relationships is between partners from different ethnic groups.

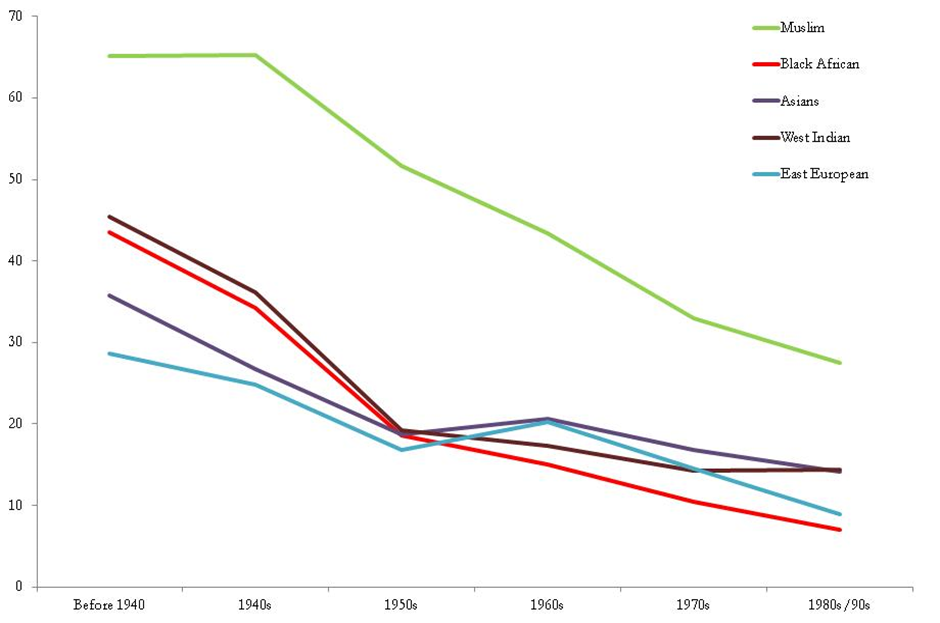

Figure 2: Generational differences in attitudes to intermarriage of a close relative with different groups

In the 2013 British Social Attitudes report, we asked about intermarriage with a wider range of groups. Figure 2 illustrates how responses vary by the decade of respondents’ birth.

There are very large generation gaps in views of intermarriage regardless of which group is asked about, with younger Britons, particularly those born in the 1950s or later, showing consistently less opposition.

Nearly half of those born in the 1940s or earlier oppose white-black, or white-Asian intermarriage, and two thirds oppose white-Muslim intermarriage. Among those born since 1980, the equivalent figures are 14% and 28% respectively.

Muslims do stand out as a group where white Britons have much stronger concerns about intermarriage. It is not clear to what extent this reflects prejudice or worries, about the problems posed by large cultural differences, but in any event the same pattern of steep generational decline is evident here as well.

Whatever the concerns may be, younger generations of Britons are far less likely to share them.

—

This post originally appeared on the Unviersity of Manchester’s Policy Blogs and displays research the universities’ Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE).It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Dr Rob Ford is Lecturer in Politics at the Unviersity of Manchester, and the co-author with Matthew Goodwin of Revolt on the Right: Explaining Support for the Radical Right in Britain

Dr Rob Ford is Lecturer in Politics at the Unviersity of Manchester, and the co-author with Matthew Goodwin of Revolt on the Right: Explaining Support for the Radical Right in Britain

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

A close inspection of the British Social Attitudes Survey shows that racial prejudice is in long-term decline https://t.co/rVE0kjeICQ

https://t.co/GyGelHmC3s interesting read!

Good piece by @robfordmancs on racial prejudice over time https://t.co/GNDOfCNXax

A close inspection of the BSA Survey shows that racial prejudice is in long-term decline says @RobFordMancs https://t.co/padKIi0VRe

Close inspection of the British Social Attitudes Survey shows that racial prejudice in the UK is in long-term decline https://t.co/E0AlkcCLYx

The British Social Attitudes Survey shows racial prejudice is in long-term decline https://t.co/cJ3t1dflmY #racism https://t.co/OXy8Dhwffd

After tosh written in the wake of the BSA Survey, this on decline of racial prejudice is good – https://t.co/jzdXlcuViR via @democraticaudit

A close inspection of the British Social Attitudes Survey shows that racial prejudice is in long-term decline https://t.co/JTGweccmVI