What explains mainstream party decline across Europe?

In new research on party systems in 16 European countries, Jae-Jae Spoon and Heike Klüver demonstrate that, as mainstream parties have converged towards the political centre, voters are switching support to more extreme parties on the right and left. This has significant implications for how mainstream parties can distinguish themselves while still attracting voters, and for government formation in increasingly fragmented systems.

Picture: Tim Reckmann/(CC BY 2.0) licence

The European party space is changing. Across Europe we have seen mainstream parties losing votes to parties on the far left and far right. In Germany, both the Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (Christian Democratic Union; CDU) and Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (Social Democratic Party; SPD), for example, lost votes in the 2017 federal elections to the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany; AfD). At the same time, we are seeing the rise and electoral success of left-wing anti-austerity parties such as Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain and regional parties such as the Scottish National Party. What explains this electoral volatility?

In our recent article, we show that the rise of extremist parties can be attributed to mainstream parties becoming too similar and voters looking for alternatives with more distinct positions. As mainstream parties converge, voters switch to a more extreme party. We arrive at this conclusion by examining over 100,000 vote choices of individual voters in 30 elections in 16 West and East European countries from 2001 to 2013 using post-election surveys from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems. Building on prior work by Downs (1957) and Kitschelt (1995), we explain this finding with the space that opened up on the fringes of the policy space. As mainstream parties have become more similar, many voters have no longer felt represented by established parties and have looked for alternatives which better represent their preferences. Extremist parties on both sides of the ideological spectrum have benefited from the mainstream parties’ move to the centre.

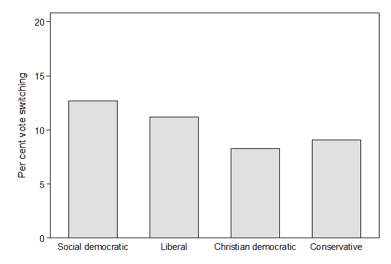

Figure 1: Vote switching across mainstream party types

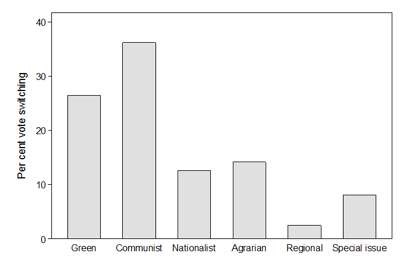

Figure 2: Non-mainstream parties benefiting from vote switching

As Figure 1 demonstrates, voters are switching from both left-wing and right-wing mainstream party families, though the highest rate of switching (12.7%) comes from voters who had previously supported left-wing parties. Figure 2, conversely, shows where the voters are going when they abandon a mainstream party. Among the vote switchers, 36% voted for communist parties, 26% voted for green parties, 14% voted for agrarian parties, 13% voted for nationalist parties, 8% voted for Eurosceptic or special issue parties and 2% voted for regional parties.

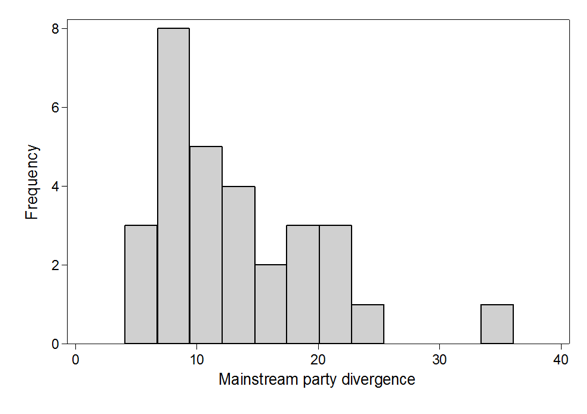

To examine how similar parties are becoming, we measure mainstream party divergence as the standard deviation of the left-right policy positions of all mainstream parties in a country at the current election using the Manifestos Project. Robustness checks using a variety of different measures for mainstream party convergence confirm our findings. Figure 3 illustrates mainstream party divergence for all the mainstream parties in the selected countries between 2001 and 2013. As the graph demonstrates, a high percentage of mainstream parties’ positions have converged with other parties. Roughly 40% of the party systems we analysed have a divergence value of 10 or below, meaning that we are seeing parties becoming more similar.

Figure 3: Mainstream party divergence across elections

We find that mainstream party divergence has a statistically significant negative effect on the probability of switching from a mainstream to a non-mainstream party controlling for individual-level, party and party-system factors. Thus, as mainstream parties converge on the left–right scale, the likelihood significantly increases that they lose their supporters. More specifically, when the ideological differences between mainstream parties decrease as they move closer to each other, their supporters are more likely to vote for a non-mainstream party at the next election. In sum, this evidence of voter behaviour offers a clear explanation of the electoral volatility – mainstream parties losing votes and new and more extreme parties attracting voters – we have witnessed across Europe.

Our findings have three important implications.

First, if mainstream parties want to continue attracting voters, they will need to better differentiate themselves from their competitors. However, this presents somewhat of a challenge, as we know that most voters lie in the centre of the ideological spectrum. Thus, established parties cannot differentiate themselves by taking a policy position that is too far removed from the median voter, yet at the same time, they have to take a position that is different enough from their rivals. The implication is that, rather than pursuing a strategy that appeals to the median voter, mainstream parties should concentrate on representing their electoral base. They should adopt a policy programme that caters to the specific demands and preferences of their supporters and allows for differentiating themselves from their competitors. This is far from trivial given that traditional voter milieus and cleavage structures have changed dramatically over the past decades. The decline of the working class as the stronghold of social democratic parties is just one example of this.

Second, as long as mainstream parties follow a strategy of convergence on the median voter, they will continue to lose votes, and new parties on the fringes may continue to develop and attract voters. This could result in increasing the size of party systems. Across Europe, we are witnessing moderate multiparty systems becoming ever more diverse party systems. Germany, for example, had been a 2.5 party system until the 1980s; it is now a six party system.

Third, our findings have crucial implications for cabinet formation. As party systems increase in size, it is harder to build legislative majorities in parliament as many of the new parties are located on the fringes of the ideological spectrum. For instance, while Germany was typically governed by coalition governments composed of two parties, these coalitions are no longer possible due to the significant vote loss of the SPD and the CDU/CSU and the recent rise of the AfD. As a result, voters have a much harder time predicting which coalitions are likely to form when making their vote choice and can no longer be sure that voting for a specific party will result in the preferred coalition cabinet. This may lead to considerable frustration and discontent among citizens. What is more, coalition-building not only becomes unpredictable, but it becomes much more difficult to form a government at all. It took nearly six months, for example, following the September 2017 German elections for a coalition agreement to be agreed on between the CDU and SPD, which was neither party’s preferred outcome.

The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of Democratic Audit. It draws on the authors’ article, ‘Party convergence and vote switching: Explaining mainstream party decline across Europe’, recently published in the European Journal of Political Research.

About the authors

Jae-Jae Spoon is Associate Professor of Political Science and the Director of the European Studies Center at the University of Pittsburgh. She is co-editor of the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Policy and Research & Politics. Her research interests include European politics, political parties and electoral competition. Her work has been published among others in the British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, the European Journal of Political Research, the Journal of Politics and at University of Michigan Press.

Heike Klüver is Full Professor and Chair of Comparative Political Behavior at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Her research interests include political parties, coalition governments, interest groups, political representation and quantitative text analysis. Her work has been published among others in the American Journal of Political Science, the Journal of Politics, Comparative Political Studies, the British Journal of Political Science and at Oxford University Press.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.