Do election handouts actually ‘buy’ votes?

Vote-buying is generally seen as detrimental for democracies. However, the efficacy of such bribes has rarely been studied. Jenny Guardado and Leonard Wantchékon find that there is little correlation between election handouts and support for the parties offering them. Possible explanations include the secrecy of the ballot and multiple opposing parties buying votes, and so we should be cautious about assuming they are effective.

Picture: Daniel Go, via a (CC BY-NC 2.0) licence

In many elections, particularly in the developing world, candidates and parties tend to distribute private goods such as cash and gifts around election day in exchange for electoral support or higher turnout – a phenomenon known as vote-buying (distinct from other practices of patronage or clientelism). The practice has been labelled as undemocratic and concerning by international organisations focused on transparency and the promotion of democracy. However, the veracity of this claim depends on these practices actually being effective in changing an individual’s political behaviour, leading to outcomes that would not have occurred otherwise. But, do we actually know if electoral handouts result in greater turnout or vote shares in favour of the distributing candidate?

At first glance, it seems pointless to question whether electoral handouts are effective in delivering votes. If not, political actors – considered some of the most calculating types of individuals – would be wasting scarce time and financial resources. Guided by this reasoning, a large literature in political science has sought to uncover systematic patterns in the way handouts are delivered as evidence of political strategies to purchase votes. For instance, seminal papers have found that politicians tend to target with handouts poorer voters; those indifferent between political options; with higher propensity to turn out to vote or those exhibiting intrinsic reciprocity.

Yet, very few studies have actually examined how those targeted with handouts behaved at the polling station (exceptions include Brusco et.al. (2014); Diaz-Cayeros et. al. (2009); and Cantu (2018)) . Are these strategies effective? Do those targeted actually support the politicians providing the handouts? In this paper, Leonard Wantchékon and I use insights from game theory and empirical evidence from several post-electoral surveys in African countries to tackle this question.

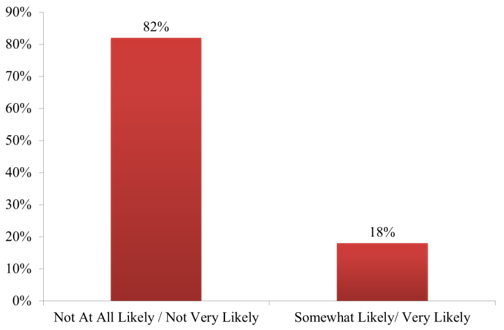

Our main argument is that the presence of electoral handouts is unlikely to sway electoral outcomes in any significant way for three main reasons. The first is the secrecy of the ballot, which prevents politicians from knowing if individuals accepting handouts voted the way they were supposed to do, weakening the vote-buying transaction. For example, a great majority of respondents across a number of surveys in Africa think it is very to somewhat unlikely that powerful people know how they voted. Specifically, 82% of respondents (excluding non-response) across 31 African countries surveyed in Round 5 of Afrobarometer report it to be very to somewhat unlikely for powerful actors to find out how they voted. In this context, is it plausible that political parties can enforce cash-for-votes transactions?

Figure 1: Vote secrecy perceptions in selected African countries

Question: How likely do you think it is that powerful people can find out how you voted, even though there is supposed to be a secret ballot in this country? Source: Afrobarometer Round 5 (2010–2012).

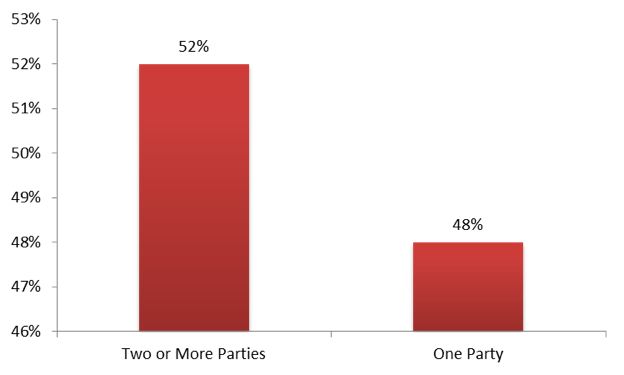

Second, electoral handouts are often delivered by more than one party. Although key studies on vote-buying assume a single distributing party (generally the incumbent) it is very likely that in multiparty democracies voters receive handouts from more than one party. This is well-known for the cases of Nigeria and India. Moreover, in the case of the Beninese elections of 2012, a majority of those reporting being offered an electoral incentive, did so from more than one party. This poses an additional challenge for politicians purchasing votes which weaken the transaction: do voters respond to the first offer, to the highest offer, or simply follow their own preferences?

Figure 2: Is there only ‘one’ party delivering handouts?

Conditional on being offered any handout. Source: Afrobarometer Round 5 (2010–2012). Country: Benin 2012 post-electoral survey.

Finally, and more crucially for our argument, there is also little statistical correlation between those receiving electoral handouts and support for any particular party. Given the widespread presence of handouts across African democracies – for example, we document how 29% of respondents report being offered handouts in Benin, 46% in Kenya, 31% in Mali and 38% in Uganda – one would expect these would be correlated with greater support for a particular political party. Instead, we find little difference in the electoral choices of those receiving handouts, and those who didn’t, in elections in these countries and Botswana.

To alleviate concerns of significant differences between individuals who receive handouts and those who do not, potentially biasing our comparisons, we focus on comparing similar individuals from the same political unit, using an approach known as matching. In fact, in the paper we show that researchers may have concluded that electoral handouts actually had an effect because they failed to adjust for observable differences between those who did and didn’t receive a handout from the same political unit.

One alternative explanation for our results would be if the vote-buying efforts of different parties cancelled out in the aggregate. For example, if parties distribute handouts at equal rates but to different populations such that the average effect on vote-choices is zero. Yet, this would require almost surgical precision in handout distribution in contexts where parties always vie for an edge, making it unlikely.

Ultimately, our null results are consistent with a growing group of studies showing how the mere presence of handouts do not necessarily translate into electoral support for the distributing party, at least this is the case for the 2011 Ugandan election, elections in Mexico, particularly the 2006 and 2012 ones, the 1993 election in Taiwan, and elections in Nigeria, to name a few. In sum, while we still do not know for certain why electoral handouts are so common during elections, future research should at least start from the premise that the effect of electoral handouts cannot be taken for granted.

This article represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It draws on the article ‘Do electoral handouts affect voting behavior?’ by Jenny Guardado and Leonard Wantchékon, published in Electoral Studies.

About the author

Jenny Guardado is assistant professor at the School of Foreign Service of Georgetown University, specialising in comparative politics and the political economy of development. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in the American Political Science Review, International Organization, Electoral Studies, World Development, among others.

Jenny Guardado is assistant professor at the School of Foreign Service of Georgetown University, specialising in comparative politics and the political economy of development. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in the American Political Science Review, International Organization, Electoral Studies, World Development, among others.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.