Blocking the Front National from power risks increasing its supporters’ disenchantment with the political system

Despite leading in six out of 13 regions in the first round of the French regional elections on 6 December, Marine Le Pen’s Front National finished in third place on Sunday. Chris Terry writes that this swing of fortunes is in a large part due to the two round electoral system used, which in many instances has resulted in the party being blocked from representation despite regularly winning upwards of 10% of the vote. He argues that by allowing this ‘blocking’ France runs the risk of furthering FN voters’ disenchantment with the system.

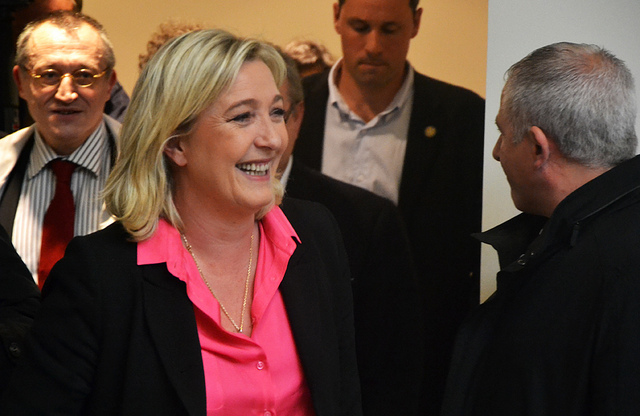

Credit: Rémi Noyon CC BY 2.0

Earlier this month the Front National (FN) came out in the lead in the first round of French regional elections. But on Sunday, in the second round of the election, the FN failed to win a single region.

The Front National has become an almost permanent fixture of French political life, having first achieved popularity in the early 1980s. The party has ebbed and flowed, infamously winning entry into the second round of the French Presidential election in 2002, but subsequently falling back until its rejuvenation under Marine Le Pen. The first round result represented a peak for the Front National in terms of its popular vote with 27.7%.

There are many reasons for the Front National’s rise, socio-economic, historical and political. But perhaps one that is overlooked is the logic of France’s electoral system.

It is well known that France uses the two round system for electing its President, where if a candidate doesn’t win 50% of the vote in the first round, the top two go through to a second round with the winner elected. The two round system isn’t just used for the Presidency though. It’s also for used for every other election, apart from Members of the European Parliament.

The French National Assembly, for instance, has a system of single-member districts like the House of Commons. But unlike the Commons, all candidates winning more than 12.5% of the votes of registered voters, or the top two parties if two candidates didn’t make it, go through to a second round. This makes France the only country in Europe besides Britain where the electoral system for its principal chamber is not proportional.

Two-round systems are used regionally too, though here the electoral system takes on a proportional-list character. Voters vote for a party list, but if no party list gets to 50% those winning over 10% go to the second round. Parties winning over 5% of the vote may merge their list into the list of another party. So, for instance, the Greens may choose to merge their list into the list of the Socialist Party. After the second round the party with the most votes wins the election, and their leader becomes the Regional President.

It is therefore possible to have what the French call ‘triangulaires’ – second rounds with three candidates, with a winner who doesn’t reach 50%. When such triangulaires emerge, parties will often withdraw in one another’s favour to stop the Front National.

For this reason, the Front National is something of a paradox. Europe’s largest and most infamous right-wing populist party is also one of its weakest in terms of representation. They currently hold only two seats in the National Assembly. This is a record haul for the party since 1986 when France briefly experimented with PR. The party has been frequently blocked from representation despite regularly winning upwards of 10% of the vote.

That pattern of being blocked from power continued again on Sunday. In their two best regions, Nord-Pays-de-Calais-Picardy and Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, the Socialists withdrew to support the centre-right candidate. In the third, Alsace-Champagne-Ardenne-Lorraine, the Socialist Party ordered their candidate to withdraw, but the local party decided not to. The Front National went down to defeat by more than 10 points in each of these regions as left wing voters came out to support the centre-right to stop the Front. This can only result in dissatisfaction on the left and act as proof to those who support the FN that the two major parties are broadly the same, a cartel against the interests of French voters.

Many will argue that blocking the Front National from representation is an advantage of the two ballot process. But it must be remembered that in addition to core issues like immigration, the Front’s voter base is driven by disenchantment with the French political system. By blocking it from representation France runs the risk of furthering Front National voters’ disenchantment with the system and encouraging support for the Front National. In a democracy it is far better that grievances are channelled within democratic institutions, rather than against them.

It also makes the Front National totally unaccountable for any of its promises. Perhaps this is why right-wing populist parties in countries with PR have often proven less stable. Several have imploded upon gaining influence – an anti-establishment movement can often suffer when it is forced to join the establishment. Populism can only be dealt with by making sure those that support it feel integrated into and listened to by the political system. In a sense then, the FN’s defeat is more a triumph of the French electoral system than other factors, such as the appeal of the other parties.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Chris Terry is a Research Officer at the Electoral Reform Society. He writes here in a personal capacity.

Chris Terry is a Research Officer at the Electoral Reform Society. He writes here in a personal capacity.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Blocking the Front National from power risks increasing its supporters’ disenchantment with the political system https://t.co/cXXYBzzRLV

Blocking the Front National from power risks increasing its supporters’ disenchantment with the political system https://t.co/U4fw7EKg4W

Blocking the Front National from power risks increasing its supporters’ disenchantment with the political system https://t.co/b8SdnpZMMp

Blocking #FrontNational from power risks increasing supporters’ disenchantment w/ political system https://t.co/dp3Me4mgln #frenchelections

Blocking the Front National from power risks increasing its supporters’ disenchantment with the political system https://t.co/SZGMJEi0st

Blocking the Front National from power risks boosting its supporters’ discontent with the French political system https://t.co/etr7gUAHp5

Me for @democraticaudit. Does blocking the Front National from power only deepen their voters’ disenchantment? https://t.co/kINJr7iJWc

Interesting piece on how French electoral system blocks #FrontNational from power, by @CJTerry https://t.co/PbA6fyVipZ #frenchelections

Blocking the Front National from power risks increasing its supporters’ disenchantment with… https://t.co/1UeiNrhnHh https://t.co/qnMcapwNPq