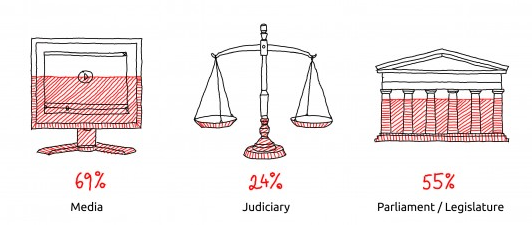

EU’s anti-corruption report shows 69% of UK citizens see our media as corrupt, 55% for Parliament, and 24% for the judiciary

This week, the EU published its first Anti-Corruption Report. It looks at corruption and anti-corruption measures in EU member states – and has naturally been controversial, being therefore serially delayed as the Commission plucked up the courage to publish it. Transparency International’s Robert Barrington argues that the report is a welcome is welcome, timely, and worrying.

The EU’s Anti-Corruption report is a very welcome. It does not break new ground, and neglects some important areas (no mention of prisons, money laundering, local government, sport, the situation in Northern Ireland, etc), but by coming from an official source rather than civil society, it is a useful reinforcement of TI’s own analysis in the areas it does cover. It will doubtless be more controversial in other countries, where corruption is more rampant, and will raise important questions about what the EU is doing to combat corruption in the states where it is worst. As part of the single market they inevitably affect other EU member states including the UK.

Fig 1: Percentage of respondents who felt these insitutions were corrupt in the UK, Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer, 2013.

The EU Anti-Corruption Report is a long document [350 pages of text], and here is a brief summary and reaction to the section on the UK.

Overall, the document is fairly much in line with TI’s own analysis, though in parts it looks slightly dated (for which I assume the delayed publication is responsible) and has some surprising gaps. The analysis is that:

- The UK does not have a strategic approach to corruption, reflected in its patchwork approach to reporting and enforcement mechanisms

- Petty corruption is at a relatively low level in the UK and there is a good tradition of ethical standards in public service

- Political corruption is a problem – citing lobbying and political party funding as areas where there are gaping loopholes

- Foreign bribery needs to be addressed – there is still fall-out from the notorious BAE Systems case, in which political interference stopped a major corruption investigation; and the government has yet to prove that it has the political will to enforce the Bribery Act

- The financial services sector has corruption issues that remain unaddressed.

In terms of recommendations, the report focuses on:

- Addressing foreign bribery, and producing sector specific guidelines for those which are high-risk – specifically citing defence

- Strengthening the governance of banks

- Requiring declaration of beneficial ownership of UK-registered companies

- Capping donations to piolitical parties

- Clarifying and strengthening guidelines for parliamentarians on gifts and assets

- Addressing issues raised by the Leveson inquiry into police-media interactions.

It is perhaps worthwhile re-capping some arguments about why the UK still needs to make an effort to combat corruption, and not ease off because it looks relatively clean when compared to Italy, for example, or Bulgaria:

- By some indicators, the UK has got worse in recent years; experience elsewhere suggests this can snowball if not addressed

- Corruption at the top – in politics – is particularly insidious, and that is where the UK is constantly shown to be both weak and in denial

- There is variance across the UK, both regionally and within institutions; that means there may be quite high levels of corruption in some cases, and certainly enough to be damaging to people’s lives

- The UK benefits from a world in which corruption is reduced; for example, corruption can distort the free market, facilitate organised crime, and create unstable states whose knock-on effects currently impact the UK in the form of terrorism, refugees or requests for armed intervention; but if the UK is to ask others to clean up their acts, it needs first to do so itself.

The good news is that the UK government committed last October to produce a national anti-corruption action plan. We published last June some ideas about what could be in such a plan – they can be found here.

The message for the UK is clear. There is definitely room for improvement, with still a remarkable indifference to corruption in the financial crisis and politics. The UK must avoid complacency – compared to some other countries it’s good, but not that good.

—

Note: this post originally appeared on Transprency International’s Blog. It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1fLN2gI

—

Robert Barrington is the Executive Director of Transparency International UK, the UK’s leading anti-corruption organisation and part of a global coalition sharing one vision: a world in which government, business, civil society and the daily lives of people are free of corruption. Transparency International fights corruption, poverty, and injustice with local colleagues in over 100 countries.

Robert Barrington is the Executive Director of Transparency International UK, the UK’s leading anti-corruption organisation and part of a global coalition sharing one vision: a world in which government, business, civil society and the daily lives of people are free of corruption. Transparency International fights corruption, poverty, and injustice with local colleagues in over 100 countries.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

EU anti-corruption report shows 69% UK citizens see media as corrupt, 55% for Parliament, and 24% for the judiciary https://t.co/dcKlSOemJ3

EU’s anti-corruption report shows 69% of UK citizens see our media as corrupt, 55% Parliament, and 24% the judiciary https://t.co/3o20VV870E

The EU anti-corruption report has highlighted some of the UK’s failings https://t.co/LGmzm4mXtU

69% of Britons believe the media is ‘corrupt’ https://t.co/PnJCK7BCZ7

EU’s anti-corruption report shows 69% of UK citizens see our media as corrupt, 55% for Parliament, & 24% judiciary https://t.co/3o20VV870E

Interesing blog by @TIukED on ‘EU anti-corruption report has highlighted some of the UK’s failings’ @democraticaudit https://t.co/Rz6kpAwPJ7

The EU anti-corruption report has highlighted some of the UK’s failings https://t.co/8isKtYUCuh

The EU anti-corruption report has highlighted some of the UK’s failings https://t.co/FqS9mb7cvv (via @democraticaudit)