Politicians who do not appear confident as political ‘performers’ are viewed less favourably by voters

Politicians are expected to be confident, articulate, and telegenic. But does their demenour actually affect the way that they are viewed by voters? According to research carried out by Delia Dumitrescu and her colleagues, it does, with even voters who agree with what is being said reacting negatively to un-confident and less-polished politicians.

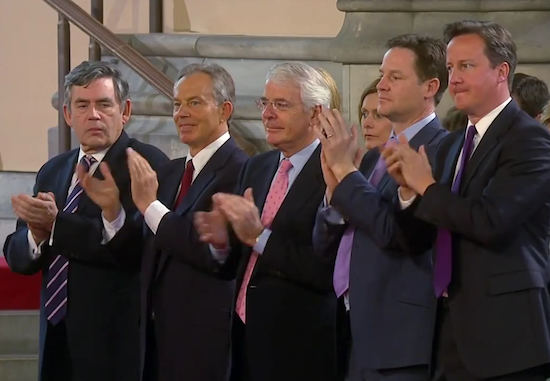

Former Prime Ministers and Nick Clegg (Credit: the White House)

Political pundits occasionally speculate that being visibly nervous hurts a candidate’s chances at the polls. But is there any evidence to back this speculation?Do candidates loose from being non-confident in front of the screen?

Previous political communication scholarship does not offer a clear answer to this question. This is because candidates do not just have a nonverbal demeanor, but also give speeches, and the verbal part of the candidate’s communication may have the lion share role in voters’ evaluations. In other words, despite pundits’ intuition, it may be that what the candidates say matters, and not how they say it.

But there is also evidence that people do form opinions of a person from how they look and act, and not from what they say. And some of this evidence stresses the primordial role of nonverbal information for evaluations, due to the automatic nature of this evaluation process.

And while there’s no real telling from previous research if a candidate can expect to lose from not being confident when delivering a speech, there is also the possibility that any evidence on the matter may depend on what type of judgement we’re talking about. For example, people have been shown to rely to a different degree on verbal or nonverbal information to decide on a person’s character or on their qualifications.

The study

We looked at the impact of showing confidence on a candidate’s evaluations using an experiment in the laboratory. Since we conducted this experiment with the participation of Canadian voters, we adapted it to the Canadian system. The Canadian system is similar to the UK one, as both countries elect just one representative per district with the candidate getting the most votes winning the seat.

To produce a naturalistic setting we watched speeches of Canadian candidates on Youtube and created a similar video and audio setting for our laboratory experiment. We hired a middle aged actor whom we pretested among other actors to look about average, neither too old, nor too young, neither too attractive, nor too unattractive. We then asked him to video record four speeches that were different only with respect to some key features.

In one speech, the actor gave a well-structured, well-articulated and well-informed speech while exhibiting clear signs of confidence. Such signs were an upright, slightly backward leaning body pose with open arms and firm gestures. We then asked him to give the same speech while acting non-confident, that is, while having a bent back, with his hands crossed and without making many gestures. In two other experimental conditions, he gave a poorly structured, poorly informed speech either with the same confident attitude or with the same non-confident attitude. Since we kept constant not just the person, but also most other aspects of the communication as well (for example, the candidate’s party, his clothes attire, the video background, the lighting), we are therefore confident that we can tease out the effects of a confident attitude on voters’ candidate evaluations.

To maximize our experimental control, we also asked only individuals whom we knew would be similarly disposed to the candidate’s party. Our participants were all positive about the party, and therefore had a start-up favorable evaluation of the candidate as well. Thus, the test for the importance of a confident attitude on candidate evaluations is a very conservative one.

We find that a confident attitude improved the candidate’s evaluations on two out of three dimensions. First, it improved voters’ opinions of his qualifications for being a national representative. Voters rated the confident looking version of the candidate on average 6 percentage points higher on job credentials indicators. A confident attitude had an even stronger impact on a second dimension: his perceived prospects of clinching the job, or in other words, his electability. The confident looking candidate was credited on average with 10 percentage points higher chances of winning the seat in his constituency.

But confidence is not the only factor that matters: what the candidate says has a slightly lesser, but noticeable impact as well. A well-structured, well-articulated speech drove both a candidate’s overall job qualifications and electability ratings about 6 percentage points higher. If we compare the impact of how confident the candidate looks with the impact of the quality of his speech on these evaluations, we find that both these dimensions affected almost equally the candidate’s job qualifications ratings. But the confidence factor had a much bigger power on people’s opinions of how well the candidate will do at the polls.

Why is the impact of confidence on electability important? Because recent research suggests that electability is an important factor people take into account when casting their vote especially in intra-party elections, when voters find it more difficult to distinguish between candidates on ideological backgrounds, because these are too similar. This means that confidence may affect who gets selected from a party, and therefore, indirectly, the pool of candidates voters can choose from on election day.

We find therefore that the pundits’ intuition that not being confident hurts a candidate’s chances can be right, even when voters are sympathetic to the candidate’s party (as opposed to undecided). This may be bad news for those who think the quality of the discourse should carry the day, but the glass is only half empty. In fact, the quality of the discourse matters as well, and if you add them together, it’s the candidate who not only is confident but also gives a well-structured speech who ends up winning the people’s support.

—

This piece is based on the following article: Dumitrescu, D., Gidengil, E., & Stolle, D. (2014). Candidate Confidence and Electoral Appeal: An Experimental Study of the Effect of Nonverbal Confidence on Voter Evaluations. Political Science Research and Methods, 1-10.

Note: this piece represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit UK, or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Delia Dumitrescu is Postdoctoral fellow in the Multidisciplinary Opinion and Democracy Research Group at the Department of political science at the University of Gothenburg

Delia Dumitrescu is Postdoctoral fellow in the Multidisciplinary Opinion and Democracy Research Group at the Department of political science at the University of Gothenburg

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

We may say we don’t like telegenic politicians, but their charms work on us anyway: https://t.co/eR3qLmps0l via @democraticaudit #compol

AS voting behaviour: how successful politicians are successful performers. What makes a good leader https://t.co/sAx6j5yQRh

Politicians who don’t appear confident as political performers are viewed less favourably https://t.co/aPtTmexMpg https://t.co/r88G5HrtJh

RT @LSEPubAffairs: Politicians who don’t appear confident as political performers are viewed less favourably https://t.co/S5jtlVtD7o no shit

Politicians who do not appear confident as political ‘performers’ are viewed less favourably by voters https://t.co/OQ8QV6umdu

Do politicians need to be confident? Yes. Even voters who agree react negatively to un-confident politicians. https://t.co/miVBDwMfzu

Politicians who do not appear confident as political ‘performers’ are viewed less favourably by voters https://t.co/GqoHTbmZdC

Read about Dumitrescu’s article in PSRM https://t.co/LpAQSsSMbm still free to view at… https://t.co/QGnlpNUvoJ

Politicians who do not appear confident as political ‘performers’ are viewed less favourably by voters https://t.co/fRH9xNa0W5