Everything you need to know about the regional contests in the European Parliament elections across the UK

The Democratic Audit team have been running a series of posts previewing the European Parliament elections in the UK on a seat-by-seat basis. Here, the team summarise these previews, while providing additional information about the electoral systems in use for the contest, and a set of simplified ballot papers which show each candidates actual chances of being elected.

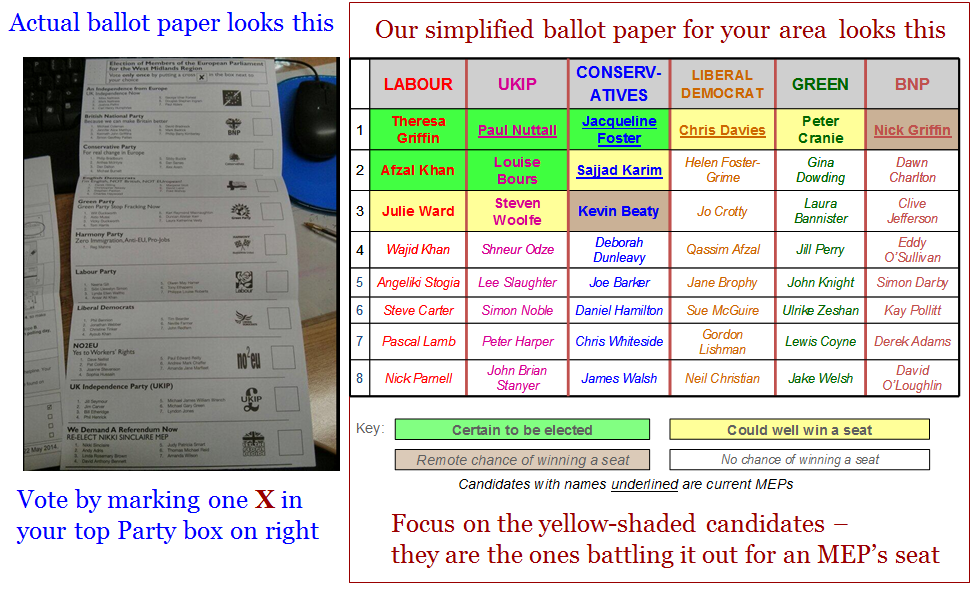

On Thursday 22 May voters across the UK can vote in the elections for the European Parliament, using a List PR system of voting. All the main parties, and a good many fringe parties too, have put up far more candidates that they can ever elect, creating huge ballot papers stuffed with the names of people who can never in fact be elected. This creates a great deal of unnecessary problems for voters, with enormous ballot papers containing lots of parties and dozens of names.

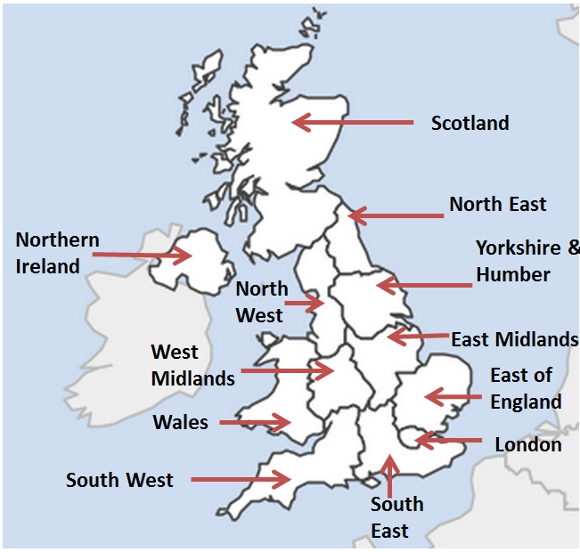

But just click on your region’s name in the Map below to go straight to a no-nonsense and completely objective account by the Democratic Audit team of;

- which parties are in contention to win a seat in your regional area,

- where the key battle lines lie between parties in your region in terms of winning seats (so you can cast your own vote as effectively as possible), and

- who are the parties’ candidates that actually have any viable chance of being elected (together with links to their record as MEPs or further details about them).

Each one of our regional summaries gives a Simplified Ballot Paper telling you which parties’ candidates are already pretty certain to be elected, which candidates have a good chance of winning a seat, which ones have an outside chance and which have no chance. We believe that parties should inform voters accurately and only put up one more candidate than they can feasibly hope to win – but instead they have littered the ballot paper with the names of no hope candidates, trying to look as if they can win ALL the seats. Under proportional representation this can only happen if one party gets a huge majority (75 to 90 per cent) of the votes, a complete fantasy outcome. (In Northern Ireland, which uses its own STV voting system different from everywhere else, the parties each put up only one candidate – see below).

How the List PR voting system works

On the very large ballot papers that you get in the polling booth you cast a single vote, by marking an X in the box of the party that you most prefer. You can only back one party, and you get no choice about which of their candidates get elected. In this sense the voting system may look the same as that being used for council elections on the same day in many parts of the country, or that familiar from Westminster elections.

But votes for the European Parliament are counted up and allocated in a completely different proportional representation (PR) way. The country is divided into just 12 large regions (actually the Government’s Standard Regions), ranging in size from the South East (10 seats) and London and the North West (8 seats each) down to the smallest regions, the North East and Northern Ireland (which have only 3 seats each). The main parties (as we have seen) all perversely select enough candidates to contest all of a region’s seats (while smaller parties may only contest some of the available seats). The parties arrange their candidates in an order, to form what is called their List, where candidates are ranked from the top in the order that the party will win seats if get enough support.

We then count up all the votes in each region and for each party we give seats to candidates from its list in proportion to the party’s vote share. So, suppose we have a region with 10 seats where party A gets 40 per cent of the vote – they should end up with 4 of the available seats. The system is very proportional but it tends to favour the larger parties somewhat, especially if many votes are heavily fragmented across many smaller parties. List PR is used widely across Europe for electing national parliaments, as well as the European Parliament.

An overview of the competition for votes in each region or country

The East of England has seven MEP seats up for grabs here. The last time these seats were contested, the Conservatives won three seats, UKIP two, and the Liberal Democrats and Labour one each. The defection of David Campbell Bannerman to the Conservatives means that the Conservatives are nominally defending three seats. The same four top parties are in contention again this time, with UKIP and the Conservatives likely to occupy the top two places, and Labour far more competitive for winning a second seat. The Liberal Democrats will be hoping to hold onto their incumbent MEP Andrew Duff.

The East Midlands constituency has five seats. In 2009, the Conservatives finished first (winning two seats), with Labour, UKIP and the Liberal Democrats each winning one apiece. The defection of Roger Helmer to UKIP has boosted their compliment to two and reduced the Conservatives to one seat for the region. A similar dynamic is in play in 2009, with Labour no doubt being more competitive than their nadir of last time around. In this region, three incumbent MEPs for the Tories, Labour, and UKIP are shoo-ins for election, while another four candidates stand a decent chance. The Green Party’s number one candidate has an outside chance of election.

London returns 8 MEPs to Brussels and has some of the most diverse politics in the UK. The top five parties are in contention to win at least one seat, including the Greens and Liberal Democrats. In 2009 the Conservatives came first, with Labour a disappointing (for them) second, while UKIP, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens each returned one MEP. This time around, the battle for first place will be between Labour and the Conservatives (who can aim to win between one and three seats each), with UKIP also hoping to run more strongly in a generally more pro-European region, depending on how far they surge nationwide. The Liberal Democrats and the Greens will be hoping to hold onto their MEPs, and the Greens will hope to expand their votes also.

The North East region is England’s smallest, returning just three MEPs. This sometimes makes elections rather predictable, since PR does not work well with so few MEPs. Since 1999 the three seats have been shared between Labour, the Conservatives, and the Liberal Democrats (as happened in 2009). However, UKIP are now looking to challenge the three main parties all the way (with the Liberal Democrats at particular risk of losing their MEP). The small size of the constituency makes it a hard challenge for the Greens or any other smaller party to crack, since you need to get perhaps a fifth of votes to have a hope of winning a seat here.

The North West region is one of Britain’s largest, returning eight MEPs to the European Parliament. Traditionally, this is a Labour-friendly region, though the Conservatives finished first here in 2009 and gained three MEPs, of which they will struggle to retain more than 2. The contest for first place this time is probably between a strongly revived Labour and a surging UKIP, though the Conservatives will be hoping to maintain their vote share. The Liberal Democrats will also be hoping to hold onto their single seat. The struggling BNP will be hard put to retain their current seat.

Northern Ireland will elect three MEPs using a completely different PR system, called the Single Transferrable Vote (STV). Along with the entirely different make-up of viable political parties thanks to the embedded Catholic/Republican – Protestant/Unionist divide, the result in Northern Ireland will look very different to any other part of the UK. In 2009, Sinn Fein finished first, with the UUP (Ulster Unionists) coming second, and the DUP (Democratic Unionist Party) third. The SDLP (Social Democratic and Labour Party) came fourth, missing out on a seat. This year the same four parties will battle for one of the three seats, with interest focusing on who tops the poll, if the DUP come out as top party on the unionist side, and whether the SDLP does any better against Sinn Fein after the recent arrest of Gerry Adams.

Scotland elects six MEPs, and also has a distinct party system from England, with the Scottish National Party (SNP currently the dominant force and running the government at Holyrood. In 2009, the SNP gained two MEPs on around 30% of the vote. Labour, traditionally strong north of the border, also returned two MEPs but on just over a fifth of the vote, while the Conservatives gained one MEP on 17% of Scottish voters. The Liberal Democrats came in fourth, also returning an MEP. This time, the SNP will be looking to see if they might just further boost their MEPs to 3, while Labour as the main opposition to Cameron-Clegg coalition should recover sharply in votes. The long-serving Conservative incumbent Struan Stephenson has stepped down, so it will be interesting to see if the Tories can retain their seat, and the Liberal Democrats will be looking to hold onto their single MEP. The big challenge for both is UKIP, which has not previously done well north of the border, but is now in contention. Across all the parties only three candidates can be truly confident of re-election (the top two SNP candidates and Labour’s top candidate) with another four in with a good chance, and four more having an outside chance.

The South East is the UK’s biggest European Parliament constituency, returning 10 MEPs. In the past it has also been a ‘safe’ region for the Conservatives Party, who last time won four seats at the on almost half the votes. This year they are in much stronger competition with UKIP for top place, with Farage’s party gaining at least three seats. A rebuilt Labour vote should see the party being competitive for two seats. The Liberal Democrats will be hoping to hold onto their one seat and minimize the damage to their vote share. This is a key region for the Greens, who will want to retain their current MEP and grow their vote further. Realistically, 12 candidates are in with a strong chance of winning one of the 10 seats, while another five have an outside chance.

The South West region has six MEPs. In 2009 the Conservatives finished first, returning three MEPs, to UKIP’s two, and the Liberal Democrats’ one. This dynamic is still present this year, but now with a surging UKIP and a much stronger Labour Party back in contention for one seat. Only three candidates can be absolutely certain of being re-elected.

The West Midlands now has seven MEPs (in 2009 it only had 6). In Westminster terms the region’s large rural areas tend to be politically dominated by the Conservatives, while the more urban areas are friendlier to Labour. In Euro elections it is a ‘swing’ region, where UKIP, Labour and the Conservatives will all be vying for top place. In 2009, the Conservatives finished first and elected two MEPs, and UKIP also gained two, while Labour and the Liberal Democrats each returned one candidate, finishing third and fourth respectively. UKIP will be hoping to make further inroads here and might even win three seats here if all goes well for them. The Liberal Democrats have been a presence in the region, but with their vote squeezed they will struggle to hold onto their MEP.

Yorkshire and the Humber elects six MEPs. It will see Labour, UKIP, the Conservatives, Liberal Democrats and (to a lesser extent) the Green Party in the mix for a seat. In 2009, the Conservatives finished first, so they are defending two seats. Labour came second, and along with UKIP and the Liberal Democrats secured one seat. This time Labour has revived and the Tories’ northern support may dip, while this is a strong region for UKIP also. There has been a large turnover of retirements and defections of MEPs in the region since last time, which may have an effect. Though the BNP won a seat here last time their erstwhile MEP Andrew Brons has since left the party and their vote has collapsed nationwide. Our preview suggests that only three candidates (the first placed candidates for Labour, the Conservatives and UKIP) can be confident of re-election, while four more have a decent chance, and another four have an outside chance.

Wales returns only four MEPs but has an enlarged party system thanks to the strength of Plaid Cymru (a Wales-only nationalist party). In 2009, the Conservatives finished first, Labour second, and with Plaid and UKIP third and fourth respectively. In a typical proportional outcome each of the top four parties got one seat, despite a difference of around 10 percentage points between the first and fourth placed parties. This time Labour has revived and is perhaps in contention to win a second seat if it did really well. The Conservatives and Plaid look likely to see their top placed candidates re-elected, so the battle for the last seat is likely to be between UKIP and Labour. In such a small region the fifth and sixth parties, the Liberal Democrats and Greens, struggle to have any chance of winning a seat.

—

Click here to see all of Democratic Audit’s previews of the European Parliament elections

Note: please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1o52zPc

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Can I ask who decides how many MEPs each region can have?

@JGreenbrookHeld Not personally, but I did make this sweet map for @democraticaudit https://t.co/qOC8fT6F4a

How the voting works in England for the Euro elections – was wondering if it was divided into areas and it is https://t.co/vhFjPKAq0F

Nice mention of DA’s briefings (https://t.co/o5LJLTq45w) on @andrewsparrow’s live-blog of today’s elections https://t.co/RSBg0KFu4g

Still time: Everything you need to know about regional contests in the European Parliament elections across the UK https://t.co/mTq7wADYm8

Useful:Everything you need to know about the regional contests in the European Parliament elections across the UK https://t.co/4xasUA3MV9

RT @PJDunleavy: Everything you need to know about how to vote in the European Parliament elections – regional breakdowns https://t.co/mTq7wA…

Everything you need to know about the regional contests in the #EP2014 across the UK. https://t.co/KR5c34xLja by @democraticaudit

A must-read https://t.co/7G23nY8SBl

All you need to know for how to vote in the European elections today : https://t.co/2QEUpvMxaR

Everything you need to know about how to vote in the European Parliament elections – but the parties’ misinforma… https://t.co/h26cLgTxeC

RT @BMHayward: 22 May European parliament elections polling booths open 7-10pm today-info by @democraticaudit https://t.co/EXIxq5PSv0 http:/…

RT @democraticaudit: Still not decided how to vote in Euro elections? Check out our guides for every region https://t.co/cVwhPjWEQD

RT @sonalijcampion: Useful stuff from @democraticaudit “Everything you need to know about the regional contests in the EP elections” http:/…

Everything you need to know about the regional contests in the #European Parliament #elections across the UK. #EP2014 https://t.co/ov6Oxv1vsk

RT @PJDunleavy: Everything you need to know about your region’s contest in today’s European Parliament elections across the UK https://t.co/…

[…] The guide to the European elections at Democratic Audit UK is particularly good. There’s an overall guide, and detailed regional ones too. […]

[…] The guide to the European elections at Democratic Audit UK is particularly good. There’s an overall guide, and detailed regional ones too. […]

Everything you need to know about the regional contests in the European Parliament elections across the UK https://t.co/mTq7wADYm8

RT @se_kip: The fruits of my labour over the past few weeks: @democraticaudit previews each of the 12 UK European Parl contests https://t.co…

If you can’t decide how to vote in Euros tomorrow, ask @se_kip for his intimate knowledge of every (viable) candidate https://t.co/ZaoQkCs3dr

RT @AGKD123: This is excellent from @democraticaudit telling you all you need to know about voting in the Euro elections #EP2014 https://t.c…

[…] The Democratic Audit team have been running a series of posts previewing the European Parliament elections in the UK on a seat-by-seat basis. Here, the team summarise these previews, while providin… […]

Everything you need to know about how to vote in the European Parliament elections

https://t.co/8FXBEpKImx

Everything you need to know about how to vote in the European Parliament elections (w/ interactive map) https://t.co/cUhEuq8nPA

Totally brilliant! From @democraticaudit everything you need to know about tomorrow’s @EPinUK_edu elections: https://t.co/RWrkQC3eoZ

Enormous thanks to image editing guru @chrishjgilson for his help making this interactive map! https://t.co/xFpm0HGMh2

Everything you need to know about how to vote in the European Parliament elections – but the parties’… https://t.co/tMSDBdxOQq