Taking democracy seriously demands that we identify and address the danger of oligarchy

Republican political theory has undergone a renaissance in recent years. Philip Pettit and Quentin Skinner have identified a certain understanding of liberty as central to republicanism and Pettit argues that we must make democratic institutions ‘contestatory’ to secure liberty in this sense. John McCormick, drawing on Machiavelli, argues that we need to be alert to the dangers of oligarchy and consider innovative institutions to check this danger. Stuart White argues that both perspectives should inform our approach to democratic renewal.

Republican political theory has undergone a marked revival in recent years. The work of Philip Pettit and Quentin Skinner has been particularly influential. At the centre of their reconstruction of republicanism is a particular way of thinking about freedom. Skinner argues that in Roman law, the status of a free person is understood in contrast to that of a slave. What characterises the slave’s position is that he or she lives subject to another’s power to interfere in their actions at will. The slave is the subject of another’s power of arbitrary interference. In the neo-Roman view then, freedom consists in the status of not being subject to another’s power of arbitrary interference. The free person does not live under the shadow of a powerful party, able to intervene at the power-holder’s discretion. Pettit refers to this as freedom as non-domination. In Pettit’s account of republicanism, freedom as non-domination becomes the key objective. The state’s role is to use its coercive power to create social conditions in which, in our relations to one another, we are secure against domination.

For example, it is part of the state’s responsibility to craft laws around property, taxation and social policy to help ensure that citizens do not suffer the economic deprivation that might otherwise render them dependent on, and dominated by, the better off. At the same time, however, the republican will want to structure the state so that it, too, is unable to make us the subjects of an arbitrary will. In a recent interview, Skinner argues that the recent revelations about the wide scope of the state’s power of surveillance of our digital communications point precisely to a power of arbitrary interference: such surveillance is not only a threat to privacy, he argues, but to liberty itself by virtue of the apparently wide degree of discretion state officials have to monitor citizens’ communications.

How, in very broad terms, can we help ensure that the state’s power of interference is appropriately constrained so that it is not a power of arbitrary interference?

Here we come back to the idea of the common good. A republic is a state ‘that is forced to track the common interests of its citizens’. In common with Rousseau, Pettit thinks that citizens share certain basic interests: common recognisable or avowable interests. A legitimate state is one that uses its coercive power to pursue these interests for citizens – and only to do this.

What is crucial, however, is not just that the state does pursue the common good but that it ‘is forced to track’ this common good. It is when the state is constrained to track the citizenry’s common interests that we can say its coercive power is non-arbitrary. The state cannot then do as it likes, act on its whim. It must act in accordance with its proper purpose. How is this constraint achieved?

Part of the answer is that the people must be able to use standard democratic devices such as elections to exert influence over lawmakers, thereby helping to ensure that their decisions track common interests. However, in Pettit’s view, electoral accountability is only part of the answer. There is always the danger of a ‘tyranny of the majority’ in which a section of the community uses electoral power to lord it over a persecuted minority. To help prevent this, Pettit argues that democracy must be ‘contestatory’. It must provide institutional devices that help citizens to contest proposals and decisions, even those that might initially have strong majority support.

A good example of the sort of thing Pettit has in mind is provided by a recent case in the UK. In January 2012 the Coalition government’s Welfare Reform Bill went for its second reading in the UK parliament’s second chamber, the House of Lords. Although unelected, the Lords is understood to be parliament’s ‘revising chamber’, examining bills passed in the Commons with care and making amendments. In this case, confronted with a controversial bill, and arguably responding in part to a very effective campaign by a group of welfare and disability rights activists (the Spartacus campaign) the Lords voted through a number of significant amendments to the government’s bill. However, when the bill returned to the Commons, the government invoked the doctrine of ‘financial privilege’ to claim that it was entitled to ignore the Lords’ amendments.

There was some controversy as to whether this was an unusually broad use of the financial privilege doctrine. But the key point is that, no matter how innovative this use of the doctrine was, the Commons was able to ignore the Lords. For campaigners, the Lords was perceived as a key point of contestation in the UK’s democratic system: a point where they, as citizens, could bring arguments to bear, persuade lawmakers of their case, and so possibly limit a bill that they saw as insensitive to the interests of many disabled people. But it turned out that a victory at this point in the political process was hollow. The government, backed by a compliant majority in the House of Commons, forced through its bill without any pressure to respond to the arguments of the critics. The House of Lords turned out not to be a point of contestatory power within the UK polity.

A democracy is contestatory to the extent that citizens do have access to points in the political system that they can use to pressure policymakers into reconsidering their proposals or decisions. Bills of rights can be particularly important here in that they capture some of the citizenry’s permanent common interests and so provide an important reference point for contesting government proposals and decisions in terms of the common good.

Republican democracy is, then, as for the deliberative democrat, at its core a collective search for the citizenry’s common good. We enter the forum, ideally, with the goal of advancing common interests and 02: White persuading fellow citizens of what might constitute the common good – and of learning with an open mind from them about what this could involve. But republican democracy is also, as for the agonist democrat, a matter of ongoing conflict. We enter the forum ready to persuade fellow citizens of a policy opposed by other citizens, and whose opposition we do not (and should not) expect simply to go away. Pettit draws attention to this aspect of his theory when he contrasts it with what he sees as the ‘communitarian’ theory of Rousseau (Pettit 2012: 11-18). Whereas Rousseau allegedly expects the citizen in the minority to accept and comply with the majority’s decision, the republican view imagines a ‘contestatory citizenry’ always willing to continue to oppose decisions with which they disagree.

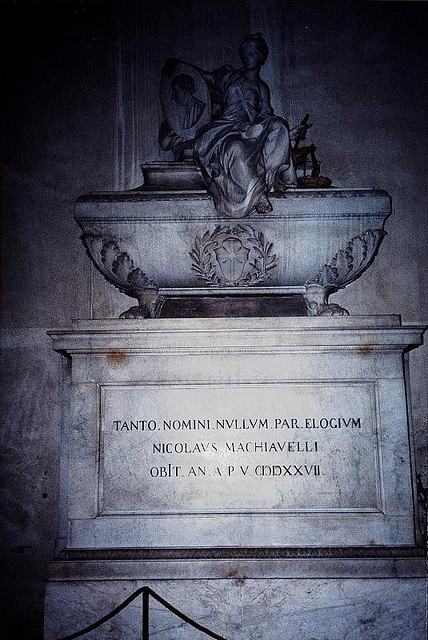

Pettit’s conception has been challenged from within the republican framework, however, by John McCormick. McCormick argues that Pettit is so concerned by the tyranny of the majority danger that he ends up advocating institutional checks and balances that render his imagined republic strongly ‘aristocratic’. Against this, McCormick advances a democratic republicanism that he finds in the work of Machiavelli. Machiavelli’s discussion of the Roman republic draws attention to various institutions that enabled the Roman people to check the authority of the Roman aristocracy. In McCormick’s view, there is an important lesson here for us today. In the classical republican tradition, the republic is a ‘mixed constitution’, combining elements of democracy and aristocracy and/or oligarchy (and perhaps monarchy), and the mix reflects a particular balance of power between social classes. However, our contemporary conception of our political system as straightforwardly ‘democratic’, with authority resting on a sovereign people, conceived in a way that abstracts entirely from social differences, arguably obscures this question of the balance of class power. This becomes very worrying when officially democratic societies become subject to increasing political domination by corporate and economic elite interests. To counter the effective power of the economic elite, McCormick argues, there is a need to revive the Machiavellian idea, drawn from the example of the Roman republic, of political institutions that serve to articulate and press the claims specifically of those outside of the elite.

To this end, McCormick proposes that the US revive and update a key institution of the Roman republic: the Tribunate. In a fundamental reform of the US constitution, a relatively small group of citizens (McCormick suggests 51 people) is to be chosen at random each year to sit on the Tribunate. They will have power to call on outside expertise of their own choosing, to assist in their deliberations. This assembly will have complete control of its own agenda. It will not merely issue recommendations, but have some degree of independent political authority. Specifically, it will have the power to put at least one proposal per year to a popular referendum. It will also have the power to veto one law made by Congress, one executive order of the President, and one decision of the Supreme Court per year; and the power to initiate impeachment proceedings against officeholders in any branch of government. Finally, in order to make it an institution that represents the people in contrast to the ‘nobles’, eligibility for the Tribunate will be limited to those in the bottom 90per cent of the wealth distribution (and, within this 90 per cent, to those who have no significant record of holding political office). In McCormick’s view, a Tribunate of this kind can help ensure that popular preferences are better represented in the political process. Its mere existence, on these terms, will also promote a certain kind of class consciousness, he argues: an awareness that society is divided into a people and an elite, whose interests are not necessarily coincident.

McCormick’s arguments resonate in light of recent work in political science which points to the growth in recent decades of corporate and elite power in countries such as the US and the UK. In relation to the US, Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson have argued that recent growth in economic inequality is best explained by a change in the representation of organised interests in the US polity, with the rise of corporate and economic elite influence as a key factor. In a number of recent books, Colin Crouch has made a similar argument that also covers the UK. McCormick’s proposal for a Tribunate is intended to address this problem and is made in a spirit of inviting further discussion. This should consider recent democratic innovations in Latin American nations and elsewhere in the global South, such as participatory budgeting in Brazil, which arguably connect with the concern to find new institutions of popular power to complement the standard institutions of liberal democracy.

Pettit is right, I think, to stress the need for contestatory institutions and devices to reduce the danger of a tyranny of the majority. McCormick underscores the accompanying danger of a tyranny of the minority – in Occupy’s slogan, the ‘one per cent’ – raising the question of whether we need to complement the institutions of conventional, electoral democracy with additional contestatory institutions – new Tribunes perhaps – to contain it.

—

The full version of this essay appears in the forthcoming book ‘Democracy in Britain, essays in honour of James Cornford’ which is published by the IPPR today. More details about the report can be found here. To see the full piece, including references, click here.

Note: this piece represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1ez76SU

—

Dr Stuart White is a Fellow and Tutor in Politics at the University of Oxford’s Jesus College.

Dr Stuart White is a Fellow and Tutor in Politics at the University of Oxford’s Jesus College.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Taking #democracy seriously demands that we identify and address the danger of oligarchy https://t.co/Fly8iCXCwk via @democraticaudit

Govt responsibility: craft property, tax, social policy so citizens aren’t deprived and dominated by wealthy #ethics https://t.co/LFia2yQNDz“

Thought-provoking blog on the dangers of oligarchy to the integrity of democratic processes https://t.co/czfZndh58D @democraticaudit

@javieraparicio: Entre la “dictadura de la mayoría” y la oligarquía https://t.co/0iR6FVZf5w file in: contrapesos.

Entre la “dictadura de la mayoría” y la oligarquía https://t.co/M87RoXmFyf file in: contrapesos

Insightful blog from @democraticaudit on the danger of oligarchy to the democratic process https://t.co/sG1FJ347RA

RT @PJDunleavy: Taking democracy seriously demands that we identify & address the danger of oligarchy https://t.co/72MVYTGQeq Stuart White h…

Political theory meets the 2012 Welfare Reform Act, raising some very old questions. From @StuartGWhite https://t.co/JHkRMZOvLK

“Taking democracy seriously demands that we identify and address the danger of oligarchy” @IPPR @StuartGWhite https://t.co/SlrGUwbcvw

According to this great piece does the republic democracy functions in Kosovo or is there simply tyranny of majority? https://t.co/d3m5qoLcYo

Another preview from @IPPR’s new book on democratic renewal. @StuartGWhite on republican #democracy @democraticaudit https://t.co/NPrE1Tp8NE

On DA today-an extract from an article in @IPPR’s new collection by @StuartGWhite on the dangers of oligarchy https://t.co/iWWx8LKIlw

Taking democracy seriously https://t.co/PKCDowmgmV @StuartGWhite

.@stuartgwhite on republican democracy, and protection from oligarchy https://t.co/nb1GWaqRcD

A remarkable time for new thinking as left & right work to defend citizens v corporate power https://t.co/R8stzob85k & https://t.co/SVyLgadwlA

Taking democracy seriously demands that we identify and address the danger of oligarchy https://t.co/3MfG6Lo1qq