All parties need to commit to a plan for young voter engagement

Electoral turnout is among young people is falling, and the disparities between young and old is worse in the UK than any other OECD country. Yet the response of politicians to youth disengagement has been tepid, argues Izzy Westbury, who suggests learning from overseas and the embrace of an ‘educate first, vote second’ plan for young people.

Closing schools on election day doesn’t help educate young people about democracy. Credit: Hilary Perkins, CC BY-SA 2.0

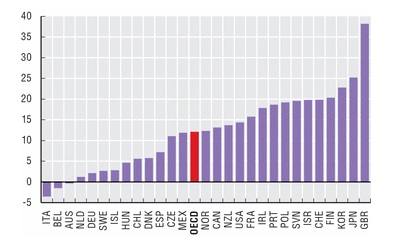

That young voters have a low turnout during elections is not a new phenomenon. However, what is new – and alarming – is that young people are now even less likely to vote than young people a generation ago. Recent data suggests that the problem in the UK is a lot worse than in other comparable developed countries. A recent OECD study showed that the percentage point difference in voting rates between 55+ year olds and 16-35 year olds in the UK is 38 per cent, much higher than any other country in the study (see Figure One below). The Netherlands near the other end of the scale only has a difference of 1.2 per cent, and even the USA has only a 14.4 per cent difference. Clearly something needs to change.

Indistinguishable parties, limited choice, a restrictive voting system and widely covered political scandals have all been proffered as reasons for the decline – and these are all legitimate. The Guardian recently published a poll showing that among voters aged 18-24, anger and boredom are the dominant feelings about politics, with the former sentiment prevailing amongst voters as a whole. However, save a radical change in politician’s conduct, these are all factors which probably won’t change, or at least not anytime soon, and radical arguments like changing the voting system to proportional representation are largely academic.

Projects such as Bite the Ballot and Rock the Vote (from the US) are admirable endeavours which, if publicised enough through the right platforms, will do a lot to engage young people through social media and student organisations. But if these campaigns are to be successful in the long run, they need to be backed up by solid policy and statute changes. One drawback is that they largely target those already in professional or academic institutions – at university for example, where the National Union of Students’ networks and resources can be used to target young voters.

Figure One: Percentage point difference in voting rates between those 55+ years old and those 16-35 years old

Source: Society at a Glance 2011, OECD. Derived from: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), Module 2 and 3 of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES)

Without changes entrenched in law, campaigns will come and campaigns will go. So far the response from politicians has been tepid, limited to the odd statement in support of a campaign or a photoshoot with the ‘not-representative-of-their-peers’ teenage party hack. Perhaps some politicians are all too aware of the limited impact such schemes will have on their immediate electoral prospects – after all, why humour a section of society that won’t keep you in office?

We need solutions that won’t falter the moment they are out of the limelight, plus those which will impact young voters as a whole, not just a proportion.

Labour have come out early with a commitment to include lowering the voting age from 18 to 16 in the next Labour manifesto. The idea is not so much that young people need empowering, but that they need educating, which is best done while they are still at school, twinned with a tangible incentive – casting a vote. The irony of closing schools on voting day is that these are the very places in which we should be encouraging participation. So, the plan is educate first, vote second. The wealth of research suggests that if we vote in the first election we are eligible for we are much more likely to continue voting throughout our lives. Interesting plan – let’s try it.

Finally, let’s have a look at strategies that have found success abroad. Another proposal for lasting policy change comes from the Institute for Public Policy Research, whose Australia-style plan is that young people should be required to vote the first time they’re eligible to do so, or face a fine. It’s a radical plan with opponents warning of the shadow of an interfering nanny state. The UN also published a guide in early 2013 pooling knowledge and best practice from numerous countries. For example Germany have a scrutinising body called Parliament Watch to hold politicians to account. Such ideas should be taken seriously here in the UK.

Young voter engagement is not a new problem, but it’s worse than it was, and it’s worse here than almost anywhere else. There are ideas and campaigns that are a great start, but what we really need is to implement long term change that’s far reaching. We’ve got a solid proposition from Labour, now let’s push for both the Conservatives and Lib Dems to commit to a plan. It doesn’t necessarily need be votes at 16, but something, anything, that will work towards rectifying the situation. Otherwise politics will become the pursuit of the few(er), not the many.

—

Note: this post was originally published by the Fabian Review. It represents the views of the author, and does not necessarily give the position of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before commenting. Shortlink for this post: buff.ly/1huCYJB

—

Izzy Westbury is a former President of the Oxford Union. Her undergraduate degree was in sciences and she is now studying law. Her political interests focus on sport, young people’s issues and foreign affairs, specifically the Middle East.

Izzy Westbury is a former President of the Oxford Union. Her undergraduate degree was in sciences and she is now studying law. Her political interests focus on sport, young people’s issues and foreign affairs, specifically the Middle East.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Very worrying> GB has huge % point gap in voting rates between those aged 55+ and the 16-34s https://t.co/PBi2hrhVYQ https://t.co/zDrDmfivzR

Izzy Westbury argues that all parties must commit to a meaningful voter engagement plan https://t.co/9RwSPWfCLW

RT @democraticaudit: Izzy Westbury argues that all UK political parties must commit to a meaningful voter engagement plan https://t.co/o0uLb…

Politieke generatiekloof? Volgens OECD is verschil in opkomst tussen 16-35 en 55+ in NL één van de kleinste in OECD. https://t.co/fciwI1WfUF

How,how to get young people voting

“@democraticaudit:All parties need to commit to a plan for young voter engagement https://t.co/HCSB7AecKy”

RT @muzrobertson: UK youth sensibly disengaged from voting, much more so than previous generations. https://t.co/inPtPxe89M https://t.co/dWVV…

All parties must act for young voter engagement. UK has huge 38% gap between young & old vote rates, Netherlands 1%. https://t.co/LEHIN3ut1j

All parties need to commit to a plan for young voter engagement https://t.co/nPQhQjHmuo