What do the Tory grassroots want from Prime Minister Theresa May?

Andrea Leadsom’s withdrawal from the Conservative race took the final leadership decision out of the membership’s hands. In the absence of a vote, Paul Webb, Monica Poletti and Tim Bale draw on a recent survey to reveal the composition and attitudes of Tory supporters, as well as their views on the party’s leadership.

Credit: Conservatives CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Theresa May has secured her place as Prime Minister and leader of the Conservatives without having to win the direct approval of her party’s membership. The original plan was for her to run against Andrea Leadsom in an election, but the latter pulled out before a vote could take place.

But that doesn’t mean the views of these Tory foot soldiers are irrelevant. Their support is important to the stability and direction of the government that May will lead. They help establish the general mood of the party on issues and set parameters within which the front bench can – or would be wise to – operate.

So while May will be delighted to have easily won the confidence of the majority of her parliamentary colleagues, she will also be aware of the need to keep in touch with the party’s grassroots supporters. She will be particularly aware of this as a former party chairman. But who are the grassroots, what do they believe in, and what qualities do they want from their leaders?

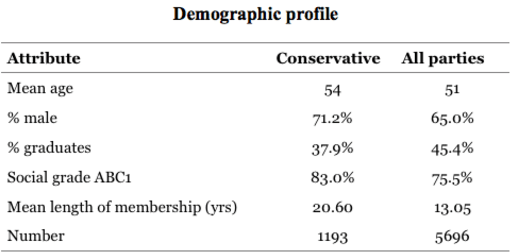

Thanks to the Party Members Project, we are able to shed some light on the matter. In June 2015, we surveyed a sample of 1,193 members of the Tory grassroots, asking a wide variety of questions about their demographic background and their political attitudes.

Portrait of a party

While some of the other parties have seen significant surges in membership recruitment since then (most dramatically in the case of Labour, of course), this is unlikely to have been the case for the Conservatives; although the official membership numbers have not been publicly updated for some time, estimates have consistently placed them at approximately 130,000-150,000 for several years now. This suggests that our sample is likely to be as representative of the Conservative membership now as it was a year ago.

Profile of Conservative members compared to general picture across the Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats, UKIP, SNP and Greens. Author provided.

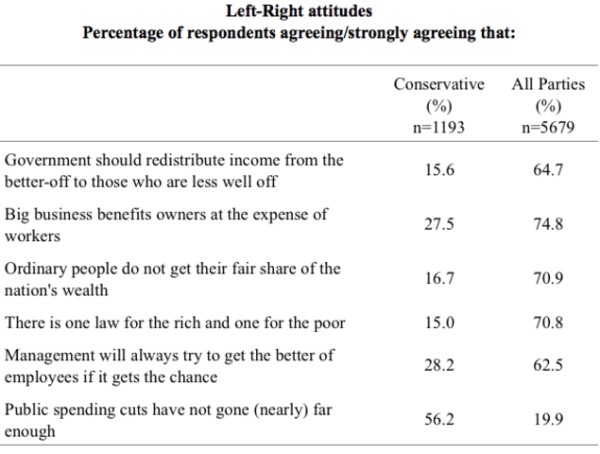

When asked questions that might indicate where they sit on the left-right political spectrum. On issues such as the distribution of wealth, far lower percentages of Conservatives agree with left-wing statements than we find across all party memberships in the UK.

When asked whether they think public spending cuts have not gone far enough (an obvious reference to the austerity policies pursued by the British government in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis), Tory members are far more likely to agree or agree strongly with austerity than adherents of other parties.

Quite clearly, then, the Conservative grassroots are distinctly right wing. What’s more, they are perfectly aware of it. We asked them to locate themselves on an imaginary left-right scale running from 0 (left) to 10 (right). The overall mean position for members of all parties was 4.44, but the average Tory member placed themselves at 7.76.

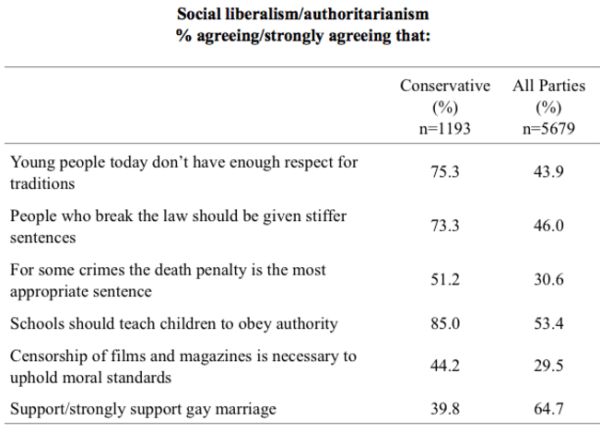

Tory members hold what might be described as “robust” views on immigration. We asked respondents two questions about immigration: is it good or bad for the economy? And does it undermine or enrich cultural life? For each of these they had to place themselves on a scale running from 1 (bad for economy/undermines culture) to 7 (good for economy/enriches culture). Their mean scores were 4.25 and 3.65 respectively – lower on the scale than other party memberships, for which the mean scores are 4.92 and 4.70.

Plainly, controlling inward migration is something the grassroots will now be hoping for. It is also an objective that singularly eluded May as Home Secretary. In the context of the EU’s commitment to the free movement of people this is hardly surprising, but as the post-Brexit Prime Minister she will have the opportunity of striking out in a new direction. The obvious challenge will be to find a way of doing this that does not inflict significant damage on the economy – something that will take considerable political skill.

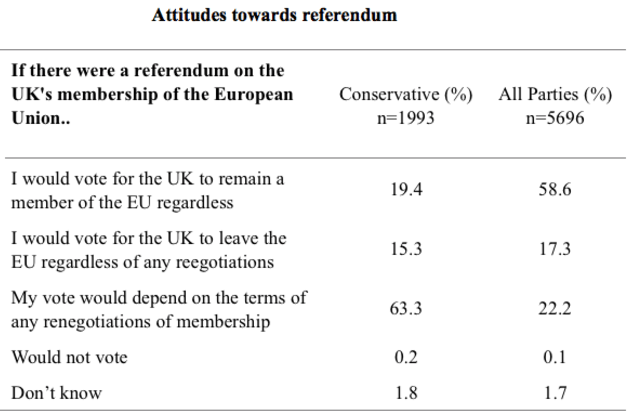

The Conservative membership showed an interesting attitude towards Britain’s membership of the EU when we surveyed them. It appears that a year before the referendum they were not determined come-what-may to vote Leave, but that their attitudes were largely contingent. Nearly two-thirds indicated that their vote would depend on the changed terms of membership that David Cameron negotiated before the referendum. Although we do not have direct evidence of this yet, it looks very like his efforts in this regard left them unpersuaded.

To characterise the majority of Tory grassroots members as head-banging Brexiteers might be misleading, then. This could have a bearing on how they regard their new leader, who was a notoriously lukewarm Remainer. It is probably not important to most of them that May was not a Leaver – especially in view of her clear post-referendum statement that “Brexit means Brexit”.

What they want in a leader

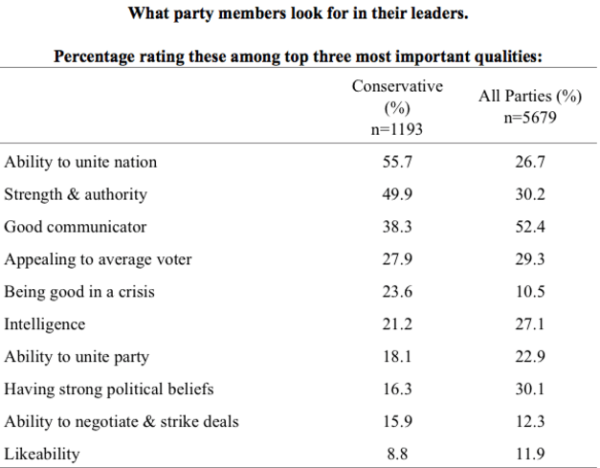

So we know a little of the general political outlook of Conservative members, but what are the specific qualities they will be looking for in their party leader? We offered respondents a list of 10 qualities, and asked them to say which they would pick as the three most important.

For grassroots Tories, it would seem that “strong” leadership, ability to unite the nation, and being a good communicator weigh most in the balance. However, the latter matters notably less for Conservatives than it seems to for members of other parties. Surprisingly, perhaps, having strong beliefs and appealing to the average voter do not figure so highly for Tory members. Rather, what stands out about them is their wish for strong and authoritative leaders who can be good in a crisis and unite the nation.

There is, perhaps, something classically Churchillian and One Nation about this skillset. Whether Theresa May has good standing in this area in the eyes of the party membership is something on which we can only speculate right now. She has the advantage of having survived that well-known political graveyard, the Home Office, longer than any politician since the 1950s, which may commend her to many. In this role she can even claim a notable triumph in her dogged determination to deport Abu Qatada from the UK, in the face of several judicial setbacks.

May’s rhetoric of late has certainly carried with it the timbre of One Nation politics and has shown a certain pragmatism. A longstanding advocate of equal pay for men and women, she has now promised employee representation on company boards of directors, shareholder votes on executive pay and an attack on inequality. She has identified her three immediate priorities as governing “for everyone, not just the privileged few”; uniting the country; and negotiating EU withdrawal successfully.

True, Theresa May’s Nasty Party conference speech of 2002 angered some Tory activists. The point she was seeking to convey to the more ideologically zealous among them was that the Conservative Party could only hope to govern again if it remained in touch with mainstream society and was not seen to pursue the exclusive, narrow-minded agenda of a select few. In this respect, her stated position this week has remained consistent – and it resonates with the membership’s desire for strong leadership that might bring unity to a fractured nation.

__

![]() Note: This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit, nor the LSE.

Note: This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit, nor the LSE.

—

Paul Webb is Professor of Politics at University of Sussex

Monica Poletti is an ESRC Postdoctoral Research Assistant at Queen Mary University of London

Tim Bale is Professor of Politics at Queen Mary University of London

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Send for Winston. What do the Tory grassroots want? A strong leader who can unite the nation. Democratic Audit […]

What do the Tory grassroots want from Prime Minister Theresa May? https://t.co/v5WzBhvfOu

What do the Tory grassroots want from Prime Minister Theresa May? https://t.co/x3H6T6IyK3

What do the Tory grassroots want from Prime Minister Theresa May? https://t.co/Slv7PbPHnh

What do the Tory grassroots want from Prime Minister Theresa May? https://t.co/6h9aM4gIWP

RE eligibility for Labour membership, it is worth noting that party membership as a whole is preserve of ABC1s. https://t.co/FiTiydHpHJ

What do the Tory grassroots want from Prime Minister Theresa May? https://t.co/HRoR1DWFcY

What do Tory grassroots want from PM Theresa May? Tim Bale et al show just how different they are from normal people https://t.co/IupfDFERQr

What do the Tory grassroots want from Prime Minister Theresa May? https://t.co/JghyOKKmDD https://t.co/zEsLthRLXk