The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic: Populists vs cosmopolitans

Varied forms of populism are on the rise on both sides of the Atlantic. Simon Reich writes that this is a result of growing disenchantment which opportunistic politicians have successfully capitalised on, and that the key political divide is no longer between right and left but between cosmopolitans favouring economic globalisation, multiculturalism and integration on the one hand and populists who favour local rule, managed trade and a greater regulation of money and people on the other.

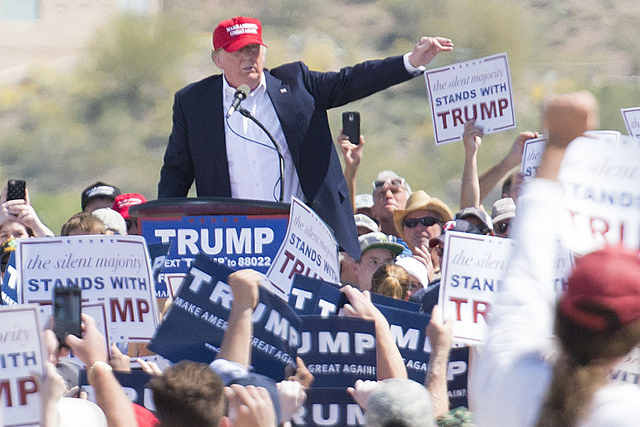

Credit: ed ouimette CC BY-SA 2.0

“Disaster narrowly averted” was the British Guardian newspaper’s view of the defeat – by only 31,000 votes out of 4.64 million – of the far right Freedom Party in Austria’s presidential elections this past weekend. But it is hard to escape the conclusion that varied forms of populism – whether anti-immigrant or more broadly anti-establishment – are on the rise on both sides of the Atlantic. Austria, I would argue, is a canary in a coal mine. A new political divide is emerging. So what is this divide, and what are its consequences?

It’s not only Austria

There is little doubt that Austria’s newfound nationalism is unexceptional in Europe. Most countries are clearly swinging to the nationalist right. In Switzerland, for example, the Swiss People’s Party garnered 29 percent of the vote in last year’s election. Polls suggest that if a presidential election were held today in France, the National Front’s Marine Le Pen would gain the greatest number of votes in the first round, at 31 percent. And this is no voting anomaly, her party having attracted over six million votes in 2015 regional elections. Even in the more traditionally social democratic states of Scandinavia, over 20 percent of Danes and 13 percent of Swedes have voted in recent elections for what are commonly regarded as far right nationalist parties. What is unexpected is that these are all relatively wealthy countries.

Disenchantment among voters is normally associated with unemployment, poverty and low levels of education. So from this perspective it’s not surprising to find support for nationalism in poorer, post-Communist countries such as Hungary, where Jobbik, the far right party, scored 21 percent in a national election on an anti-immigration, anti-EU and nationalist platform. Or in Greece or Spain, where unemployment still exceeds 20 percent. In Greece, the populist swing has been predominantly to the left with the Syriza party. In Spain it has mostly taken two forms. One is of Catalan nationalism. The other is of left wing populism. As a result, the the country has fractured into multiple parties, none capable of creating a governing coalition. Yet, like the far right elsewhere, both majority of Greeks and Spaniards still agree that they want to insulate themselves from the EU’s powers.

But Austria has some of the lowest unemployment rates in the European Union even if the rate has risen in the last two years. And it is a country that has thrived on its integration into Europe’s economy through the EU, even as the economies of some of its neighbors have shrunk. It is also a country that historically economically benefited from accepting East European refugees during the Cold War. So it should be more comfortable accepting new ones. The fact that just about half of all Austrians voted for a party that advocates disengagement from the Europe Union therefore says that something serious, and more general, is going on.

Britain and America

Neither America nor Britain is immune from these trends. In Britain, a less outwardly radical kind of populism predominates. The far right United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) shares a dislike of Brussels (aka the European Union), an opposition to migration and a love of national sovereignty. But racist leanings are less evident among its leadership, and are more hotly debated than those of its counterparts on the Continent.

Next month’s referendum about whether the United Kingdom stays in the European Union crystallizes the division between engagement or insulation that is common to all Europeans. On one side there is widespread disenchantment with the the European Union and, in particular, its relatively liberal migration flows. Polls suggest a reported 40 percent of the electorate are willing to vote for Britain’s exit. On the other hand, economists broadly agree that the evidence suggests that Britain would suffer if it left. But as in Austria, polls suggest that the overall economic health of the country often isn’t the issue.

The key question, rather, is what groups of people are suffering in the present situation. Those who feel they have been left out, their voices unheard, are pitted against the establishment, the beneficiaries of the current system.

A tale of two populisms

The American presidential campaign poses the same kind of quandary. America’s economy is relatively prosperous, with unemployment down to about 5 percent and its growth rate, if unimpressive, slowly digging the economy out of a hole. Yet the most enthusiastic support in the U.S. is for two populist candidates, Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. Donald Trump’s version resembles that often found in Europe. It is anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, anti-NAFTA and anti-free trade. He focuses on building walls to keep things out, whether that is undocumented Mexican workers or Chinese goods. Like in Europe, there is an “us” and “them” approach.

Bernie Sanders couldn’t be more different from Trump in his opposition to xenophobia. But his populism shares a hostility to free trade, with a focus on job losses in manufacturing. His supporters also share a pervasive sense of disenchantment – that people have been cheated by disingenuous politicians who have rigged the system. So from that perspective it is not surprising that some pundits posit that Sanders supporters would favor Trump in a general election against Hillary Clinton.

The cosmopolitan promise

So what are we to make of this? Well, the traditional political divide in both Europe and the U.S. has been between the left and the right. But there was a broad consensus in the aftermath of the Cold War, across partisan lines, that globalisation brought benefits. Political parties may have carried a conservative or a socialist label. But they generally implemented similar kinds of policies as leftist parties moved to the center.

When it came to economic policies, the “New” centrist Democrats of Bill Clinton resembled their moderate Republican counterparts. They favored deregulation, liberalisation, privatisation and free trade. The same was true of Tony Blair’s version of the Labor Party in Britain in the 1990s. In countries like Austria and Germany, Social Democrats governed in grand coalitions with their right-centrist counterparts. And even today, François Hollande’s Socialist government is trying to introduce labor reforms in France that have alienated his own supporters and are more reminiscent of those historically advocated by France’s conservative opposition.

For a while, these policies seemed to work. Low interest rates and the emergence of a growing middle class in places like China and India meant that there was more investment and more consumption. America’s and Europe’s economies grew.

Of course, some people got left behind as the transformation from manufacturing to service-based economies accelerated. But electorates in both continents were promised a bright future as the processes of globalization would ensure future rewards. As then American Vice President Dick Cheney claimed,

Millions of people a day are better off than they would have been without globalization, and very few people have been harmed by it.”

Any suffering would be temporary. But the Great Recession of 2008 brought that carefully constructed edifice tumbling down. From Greece to the United States, the greatest burden has been borne by very specific groups, above all the young with unprecedented levels of unemployment and manufacturing workers. The fact that the economic loss has often been concentrated in very specific geographic regions has increased the intensity of the pain. And the promised growth in wages by leaders like President Obama has not materialised, even in countries like the U.S. that have bounced back from pre-Recession levels.

The populist uprising

Disenchantment has grown. And opportunistic, populist politicians from the left or the right know how to tap that disenchantment. In major speeches, Trump has spoken out against globalisation. Sanders associates it with the one percenters and the loss of manufacturing jobs. Le Pen, for example, makes comparable arguments in France, as Hofer did in Austria. The political divide has a new dimension. It is no longer simply between the left and the right, although of course Bernie Sanders shouldn’t be lumped together with Donald Trump on all scores. His campaign is devoid of xenophobia. But the point is that a second divide has emerged. On the one hand are the cosmopolitans. They favor economic globalisation, multiculturalism and integration, and a world with diminished borders. On the other is the populists. They favour local rule, managed trade and a greater regulation of those flows – of money and of people. They reject much, if not all, that cosmopolitanism stands for.

This populist disenchantment is understandable. They were promised too much and were rewarded too little by politicians who either knew they were lying or were too stupid not to recognise that they couldn’t deliver. Now, I would argue, it is up to those same cosmopolitan politicians of different political stripes – like Hillary Clinton in the United States, David Cameron in the U.K. and François Hollande in France – to repair the mess. They need to eschew austerity programs and introduce expanded redistributive programs that reward those who have been shut out from life chances.

America serves as an example in this regard. As Hillary Clinton discovered on her recent visit to the region, the coal miners of Appalachia need new industries to which their skills can be adapted. They need government incentives to encourage regional manufacturing investment. They need educational grants for their children to go to college and escape a recurrent poverty trap. And they need avenues to enter expanding economic sectors, like health services which are so desperately poor in parts of the region.

Sorely neglected infrastructure development is another option. America’s bridges, roads and tunnels are in a state of disrepair. Indeed, such projects are more severely publicly underfunded than at any time since record-keeping began. The country missed its chance to invest in infrastructural development in the aftermath of the 2008 Great Recession. Now it has an opportunity to do so – and to address the grievances of many disgruntled supporters of populism. The disenfranchised need decent employment and a sense that politicians will deliver on their promises. Authenticity is the key to battling populism. The alternative is a world where walls get higher – both between countries and between people within countries.

___

![]() Note: This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. It gives the views of the authors, and not the position of Democratic Audit, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. It gives the views of the authors, and not the position of Democratic Audit, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting.

___

Simon Reich, Professor in The Division of Global Affairs and The Department of Political Science, Rutgers University Newark

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] is probably inevitable now anyway because, for better or for worse, as Simon Reich correctly argues, there is a new political divide in politics today—and the current party system fails to […]

[…] system is probably inevitable now anyway because, for better or for worse, as Simon Reich correctly argues, there is a new political divide in politics today – and the current party system fails to […]

[…] system is probably inevitable now anyway because, for better or for worse, as Simon Reich correctly argues, there is a new political divide in politics today – and the current party system fails to […]

The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic: Populists vs cosmopolitans https://t.co/Huj8II6Nyc

The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic: Populists vs cosmopolitans https://t.co/sEyw5IH2GV

The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic: Populists vs cosmopolitans : Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/YlrW528AfQ #BERNIEORBUST

The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic #Populists vs #cosmopolitans https://t.co/YlrW528AfQ #UPRISING #FEELTHEBERN #BERNIEORBUST

The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic: Populists vs cosmopolitans https://t.co/r0TNBBy2jZ

The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic: Populists vs cosmopolitans https://t.co/FNd9QWjFSI

The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic: Populists vs cosmopolitans https://t.co/UwHAKck8Os

The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic: Populists vs cosmopolitans https://t.co/imyvowQvbt

@Floppy See https://t.co/2hyguJjj25 plus stance on impact of AI on jobs and how to handle

The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic: Populists vs cosmopolitans https://t.co/MZslqITkA2

The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic: Populists vs cosmopolitans https://t.co/k2VruEAa2d

The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic: Populists vs cosmopolitans https://t.co/blqVFHvQid

The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic: Populists vs cosmopolitans https://t.co/rbFDt2IjC1

The new political divide on both sides of Atlantic: Populists vs cosmopolitans https://t.co/MFnLoUFaDN https://t.co/vZPwAaSZNn