Minority candidates for Westminster continue to suffer electorally from ethnic and religious prejudice

Incumbent political representatives benefit from the presence of British, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) challengers in their constituency, according to a worrying new study into the role that the race and ethnicity of candidates played in the 2010 British General Election. Summarising the research, Mary Stegmaier, Michael Lewis-Beck and Kaat Smets show that the incumbent party in a constituency typically gained at least two percentage points in vote share when they had a Black, Asian or Minority Ethnic challenger.

While Western societies are increasingly diverse in racial and ethnic composition, elected bodies fail to reflect this growing diversity. In the UK an estimated 10% of the population can be broadly categorised as BAME. Following the 2010 election a mere 4.2% of Members of Parliament were of minority ethnic status. Even though this number constituted a 1.9 percentage point increase from the 2005 elections, the political representation of BAME citizens is nonetheless clearly far below their presence in the population.

What is the reason for the underrepresentation of BAME citizens? Could it be that there are not more minority ethnic MP’s because somehow BAME candidates pay a penalty when they run for office? The question is certainly justified as research from the USA shows that Barack Obama paid a ‘racial cost’ of about 5 percentage points of the popular vote in the 2008 elections and 3 percentage points in the 2012 election. Obama’s racial background did not deny him victory, but did deny him the landslide victory that he was expected based on economic and political conditions.

The American findings prompt the question of how candidate race or ethnicity affects UK election results. Of particular interest is how the incumbent party (i.e. the party that won the constituency seat in 2005) fares when facing BAME challengers. Does the minority and ethnic status of candidates impact the local incumbent party’s vote share?

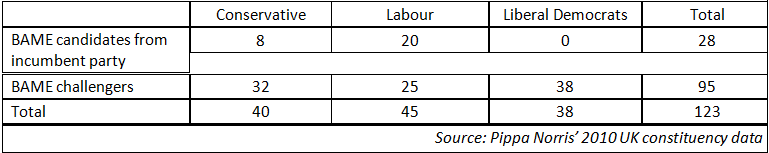

Data collected by Pippa Norris at Harvard University on candidates and their constituencies in the 2010 UK Parliamentary Election allow us to look into these questions. An analysis of the BAME status of candidates in 606 out of 650 constituencies shows that a total of 123 BAME candidates ran in the 2010 elections (see Table 1). The three major parties (Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrats) largely had the same amount of minority ethnic candidates. Most of these candidates were challengers. In other words, they ran in constituencies where their party had not garnered a plurality of the vote in 2005. The data in Table 1 obscures the ethnic and racial diversity among the minority ethnic candidates. Given the relatively small number of BAME candidates it is, however, not possible to distinguish between different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Fig 1: BAME candidates by party and party incumbency/challenger status in 606 out of 650 constituencies

The next question to answer is how the minority ethnic status of these 123 BAME candidates influences the electoral fortunes of the incumbent party in a constituency. In order to do so we looked at the influence of the candidates’ racial and ethnic background on the incumbent party’s vote share of the three major-party vote (Conservative, Labour, Liberal Democrats). If the Labour candidate won the election in 2005, then the incumbency vote share measures the Labour Party’s share of the three-party vote in that constituency in 2010. The following example explains in more detail how the three-party vote share is calculated:

Jack Straw, who served in the Labour Cabinet the full 13 years under Blair and Brown, was the Labour Party incumbent in the Blackburn constituency. In 2010 he received 47.81% of the total vote, while the Conservative challenger garnered 26.14% and the Liberal Democrats candidate got 15.2%. The other candidates received altogether just below 7% of the vote. To calculate Jack Straw’s share of the three-party vote, the following is done: incumbent party’s share of the three-party vote = incumbent party vote share/(Conservative + Labour + Liberal Democrats vote share). Therefore, Jack Straw’s three-party-vote share = 47.81/(26.14 + 47.81 + 15.2) = 53.63%

Findings show that the BAME status of the candidate from the incumbent party does not influence the vote share this party received in the 2010 election. In other words, the ethnic minority status of the candidate for the incumbent party in a given constituency does not influence the vote share this incumbent party receives. However, incumbent party candidates who run against a Black, Asian or Minority Ethnic challenger on average gain an extra 2 percentage points of the vote share. If an incumbent candidate runs against two BAME candidates this gain doubles to 4 percentage points.

The vote gain when running against minority ethnic candidates holds regardless of whether the incumbent party candidate is BAME or white. It is, thus, certainly not the case that the electoral advantages of running against minority ethnic candidates are only present for ‘indigenous’ candidates. BAME candidates from the incumbent party, moreover, do better in constituencies that have higher proportions of racial and ethnic minorities.

Analyses at the individual level using the British Election Studies of 2010 confirm the findings of the constituency level analyses. Voters in the 2010 elections were more likely to vote Labour (the incumbent party because it won the 2005 elections) in constituencies where the Labour candidate was facing BAME challengers. This result holds when controlling for the respondent’s race. Thus, while ethnic minority voters were on average more likely to vote Labour, this likelihood increases even further when the Labour candidate faced a BAME Conservative or Liberal Democrats challenger.

The 2 to 4 percentage point vote share gain the incumbent party receives when facing a BAME challenger or BAME challengers should not be underestimated. In some instances, the presence of a BAME challenger could make the difference between the incumbent winning or losing a constituency seat. Indeed, 37 elections in the 606 constituencies researched were won by a margin of 2 percentage points or less. Thus, it is a worrying indeed that in a close contest the ethnicity of the challenger could spell the difference between victory and defeat.

—

Note: this post is based on the article ‘Standing for Parliament: Do Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic Candidates Pay Extra?’, Parliamentary Affairs, 66(2), pp. 268-285 by the authors of this piece. It represents their views, and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1eUZ5Hm

—

|

Dr Mary Stegmaier is a teaching assistant professor in the Truman School of Public Affairs at the University of Missouri, Colombia. |

|

Dr Michael S. Lewis-Beck is F. Wendell Miller Distinguished Professor of Political Science at the University of Iowa. |

|

Dr Kaat Smets is a Lecturer in the Department of Politics and International Relations at Royal Holloway, University of London. |

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Minority candidates for Westminster continue to suffer electorally from ethnic and religious prejudice https://t.co/Cqsw5zm6a0

@WritersofColour have you seen this? https://t.co/HusCBIgCLX – so discouraging!

Minority candidates for Westminster continue to suffer electorally from ethnic and religious prejudice in the UK https://t.co/Jmj2NG0bCN

Ethnic minority candidates continue to suffer electorally from ethnic and religious prejudice https://t.co/GxQ6IWdXrB

Minority candidates continue to suffer electorally from ethnic and religious prejudice https://t.co/4nXs9Gf0wh

Worrying research shows that ethnic minority candidates suffer at the ballot box (in some cases) read more: https://t.co/qRwjGFsb6I

Did BAME candidates suffer electorally at the 2010 General Election? https://t.co/qRwjGFsb6I