A response to Chuka Umunna: The dominant equality issues of today need to be understood in terms of economics, interests and class

Sean Swan recently wrote an article for Democratic Audit in which he argued that the concept of class is absent from contemporary UK political debate, even though inequality in Britain is reaching new heights. Chuka Umunna, who was quoted in the piece, responded. Here, Sean continues the debate, and argues that the dominant equality issues of today are economic in nature, and need to be understood in terms of economics, interests and class.

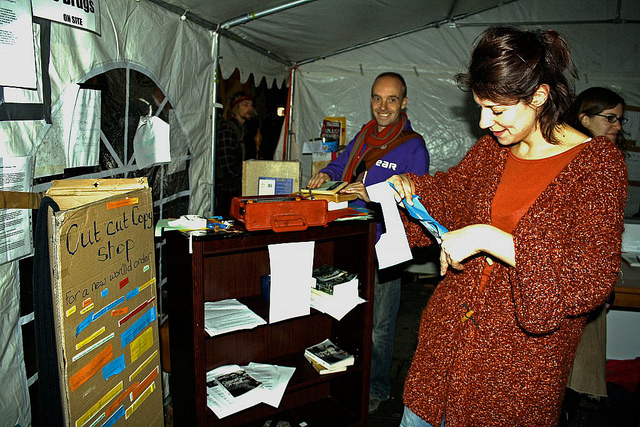

The Occupy London protest: Credit: Delaina Haslam, CC BY 2.0

Chuka Umunna, the Labour MP for Streatham, has contested some points made in my post ‘The concept of class is absent from political debate, even as inequality in Britain reaches new heights’. He takes issue with the fact that the quotes used were from the coverage of his speech in The Guardian, rather than from the text of the speech itself. He asserts that the claims made in the article were;

1) that he viewed the BAME as one homogeneous whole, and;

2) that he ignored the issue of class. Had the full text of his speech been consulted, this would turn out not to have been the case.

Firstly he points out that he does not view the BAME community as one homogeneous whole, drawing attention to the following passage in his speech;

“And I say ‘different’ deliberately because of course Britain’s ethnic minority communities are not one homogenous whole. I am part Nigerian – I am of an Igbo background – but we all know the experience of a Nigerian arriving here in the 1960s like my late father is very different to say that of a more recently arrived Somali.”

But the point in the original article was not that Mr Umunna failed to recognise diversity of ethnicity and history amongst the BAME population, but that he failed to recognise that there is no homogeneity of economic interests. As the original article pointed out, it is wrong to assume that the BAME population “shares identical socioeconomic – and thus political – interests and that an unemployed black youth in Brixton has the same political interests and concerns as a self-employed Chinese business woman in Edinburgh”. Thus it is inaccurate to view “the BAME population as one homogeneous political group” (emphasis inserted). It is difficult to see where in Mr Umunna’s speech the question of divergent economic interests is teased out. Furthermore, Mr Umunna’s position appears to be that this population ought to be, and can be, politically homogeneous. The entire intent of his speech was to woo the BAME population back to voting Labour.

Yet the increasing political diversification of the BAME population is to be welcomed. It is to be welcomed because it means that ethnic identity is becoming less politically significant in contemporary Britain. This is a result of the UK becoming a less racist, more divergent and more liberal society. The fact that the Conservatives have essentially become liberals on identity and social issues is a further reflection – and cause – of the same social trend. Mr Umunna’s mission to win back more of the BAME vote – as a specific BAME homogeneous vote – could only succeed were the direction of social development to go into reverse and ethnic identity start to become more – rather than less – socially and politically significant. But the increasing political diversification of the BAME population is a profoundly progressive sign.

Mr Umunna’s second point is that he actually does mention class as a factor in the diverging BAME vote;

“One cannot ignore the interplay with class here. The Runnymede Trust argues that there is evidence that more ethnic minority middle class voters agreed that a Conservative led government would lead to better economic policy.”

While this passage does mentions class, it does very little with it. It makes the strange assumption that it is only middle class voters who care about the economy. To speak of a generic “better economic policy” is to be entirely class blind because it assumes that there is a single economic policy which is ‘better’ for everybody. To illustrate the point, there are people who are doing very well indeed under current economic policies; there are others, and many more of them, who are doing very badly.

The result, and proof, of this is the growing economic inequality in Britain today. Thus talk of “better economic policy” must be met with the question – ‘Better for whom?’ Had Mr Umunna said that middle-class BAME voters felt that the Tories’ economic policies better reflected their economic interests – as opposed to the Tories having some generalised and abstract universal ‘better economic policy’ – then he would be correct in saying that he had addressed the issue of class as opposed to merely mentioning it.

The Conservatives’ growing conversion to a liberal position on identity and social issues is to be – and must be – welcomed. And there is no reason to believe that this conversion is simply superficial or tactical. It is the product of a more liberal Britain, but it also has roots deep in the economic interests of the groups the Tories represent and in their fundamental economic philosophy which is essentially neoliberal and globalist. The Mayor of London, Boris Johnson is the poster child par excellence of this form of conservatism. ‘Borisstan’ may be satirical, but there is more than a grain of truth in it. Boris and his ilk are a variation of what Samuel Huntington – a paleoconservative at odds with the neoliberalism of contemporary conservatism – dubbed Davos Man. Davos Man is indifferent to identity and even has “little need for national loyalty”, he “view[s] national boundaries as obstacles that thankfully are vanishing”. In neoliberal terms, discrimination by race, sexual orientation or gender is simply an irrational interference with the pursuit of profit. It is a case of pecunia non olet, one person’s money or labour is as good as anybody else’s – and cheap labour is always profitable.

This explains why migration has reached record levels under the Conservatives, and why Mr Cameron’s negotiations with the EU have focused not on migration per se, but on the question of migrant benefits. His concern is cutting social security, not migration. Even his heroic concern for British sovereignty effectively boils down to the desire to ensure that Westminster can veto any form of social, employment, fiscal or environmental regulation that might emerge from Brussels. The broad thrust of all this is portrayed in terms of national identity – a subject about which many Conservative voters still care deeply – but the detail always has more to do with protecting the City and big business.

The Conservatives turn to liberalism does not need to be understood as a new found interest in equality, but it is genuine nonetheless. The same logic that leads them to liberalism will also lead them to economic policies which will create ever greater economic inequality. And that, Mr Umunna, is why I argue that the dominant equality issues of today are economic and need to be understood in terms of economics, interests and class.

—

Note: This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. To see the original post, and Chuka Umunna’s brief response to it click here. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Sean Swan is a Lecturer in Political Science at Gonzaga University, Washington State, in the USA. He is the author of Official Irish Republicanism, 1962 to 1972.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

The dominant equality issues of today need to be understood in terms of economics, interests and class https://t.co/i0FpLj2Ijy

The dominant equality issues of today need to be understood in terms of economics, interests and class https://t.co/dMnMkE8ECu

A response to Chuka Umunna: The dominant equality issues of today involve economics, interests and class https://t.co/NG1S6wjVjT

@ChukaUmunna Equality for all pensioners abroad including BAME is essential in democratic society no discrimination https://t.co/egHBmGwMCY

A response to @ChukaUmunna: equality issues of today need to be understood in terms of economics, interests & class https://t.co/AeYTNYO9Lq

A response to Chuka Umunna: The dominant equality issues of today need to be understood in… https://t.co/55F3Oxz58a https://t.co/GoetwNCErS