Recruitment procedures shape the gender composition of party lists in European Parliament elections

Different countries select their Members of the European Parliament in different manners, with Britain opting for a party list system based on regional (in the case of England) and national constituencies (in the cases of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland). The European Parliament has better gender representation than most legislatures, however as Jessica Fortin-Rittberger, Berthold Rittberger, and Sarah Dingler argue, the recruitment procedures used by parties shape the gender composition of the lists that prospective MEPs appear on.

Credit: Grzegorz Jereczek, CC BY SA 2.0

The European Parliament (EP) has remained one of the most gender-equal elected bodies in the world. But despite the adoption of proportional representation in all member states for EP elections, stark differences exist in the share of women sent to the EP across European countries. Explaining some of these differences, we argue that political parties and their nomination procedures are crucial to explain the differential success of female candidates making it on party lists for EP elections. We find that the key to the puzzle lies in how skewed – in terms of gender composition – the initial pool of potential candidates is, as well as in the inclusiveness of the selectorate at the early stage of the nomination process.

Instead of focusing on country-specific factors such as electoral rules and societal norms about gender equality – as the majority of contributors before us have done – we shifted our focus to political parties and the ways in which they craft their candidate lists. Our premise is that political parties assume the crucial position as gatekeepers to political office, since they influence the nomination and selection of candidates at all stages of the process. To understand the dynamics underpinning women’s underrepresentation in general, and their differential success in being nominated as MEP, it is essential to analyse the role of political parties.

In our recent study published in the European Journal of Political Research, we studied over 100 political parties’ nomination procedures for the 2009 EP elections. We first disaggregate the complex recruitment procedures of political parties into multiple stages: application, approval, and candidate selection. Second, we also take into account that these stages may be affected differently by cross-cutting dimensions: the composition of the selectorate and how inclusive it is (rank-and-file or party elites), the centralisation of the recruitment process (local or national party offices) and the mechanisms through which candidates are nominated (nominations or self-nominations).

Two things stand out from our analyses. First, procedures allowing for both, nominations and self-nominations yield the most representative outcomes in terms of gender distribution. Allowing individuals to step forward and submit their candidacy along with nominations from party members therefore serves to enlarge the pool of eligible candidates and its diversity. Secondly, the inclusiveness of the selectorate at the early stage is one of the crucial determinants for gender-balanced lists. The proportion of women nominated declines with increasing exclusiveness of the initial selectorate. Moreover, inclusiveness at later stages of the candidate selection does not play out for more gender-balanced lists.

In sum, what matters most to explain list compositions leading to the 2009 EP elections is the diversity of the pool of candidates in the initial stage of recruitment, and who makes the first set of selections, rather than who makes the final decisions. If the initial pool of candidates is biased in terms of gender composition, subsequent candidate pools are also very likely to be skewed: Once the stage is set, there is no changing the cast.

Our findings suggest that the underrepresentation of women is not only the result of a shortage of qualified women willing to run for office, but also attributable to demand-side factors associated with selection procedures by political parties. Despite being the most gender-equal elected body in the world, there is still a considerable amount of gatekeeping on the part of parties when candidates are considered for the EP.

In future research we plan to expand our focus by taking into account differences in women’s representation across electoral arenas. Across our sample of political parties we make the observation that for some parties the proportion of female candidates on lists differs between contests for the EP and lower house elections.

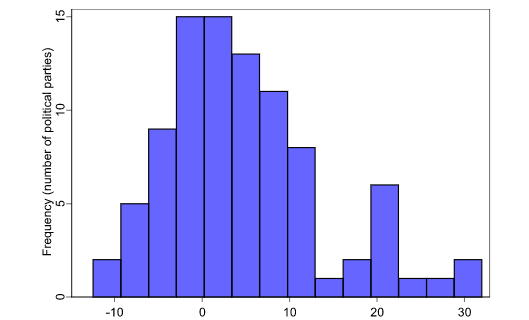

Figure 1. Difference between the percent women nominated for the 2009 EP elections and the percent women nominated at lower house elections (closest elections)

Note: Figure includes 93 political parties in 17 EU countries and shows the percentage of female candidates nominated for the EP elections minus the percentage in the corresponding national parliament (so a positive figure indicates that the percentage in the EP is higher). From Fortin-Rittberger, J. & B. Rittberger. 2015. “Nominating Women: Political Recruitment and Multi-level Representation in the EU” Paper presented at the ECPR General Conference 2015. Montreal, Canada, August 26-29.

Figure 1 highlights the difference between the proportion of women nominated for the EP elections and the most proximate lower house contest. While the differences tend to be small for most parties, we find significant differences across parties in France, Germany, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Spain and the United Kingdom. Our hunch is that we need to look at differences in how recruitment procedures operate for contests in the domestic and EU electoral arenas to account for differences in the proportion of women nominated.

Variation in territorial districting between EP and lower house elections is likely to be consequential for how candidates are nominated. Different districting in EP and national elections might result in intra-party concerns about territorial and ideological balance on lists, and thus affect the dynamics of political recruitment. It is fair to assume that such differences in candidate selection procedures can also have an impact on how gender-balanced lists are and likely have an interactive effect with district magnitude on political representation.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting. To see the full paper click here.

—

Jessica Fortin-Rittberger at the University of Salzburg. Her areas of research interest include political developments in former communist countries, political institutions and their measurement, women’s political representation, as well as the impact of state capacity on democratisation. Her homepage can be found here.

Berthold Rittberger is Professor and chair of International Relations at the Geschwister-Scholl-Institute of Political Science at the University of Munich. His homepage can be found here.

Sarah Dingler is a PhD Fellow in Comparative Politics at the University of Salzburg. Her academic profile page can be found here.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Recruitment procedures shape the gender composition of party lists in European Parliament elections https://t.co/920uWZFcT9

Recruitment procedures shape the gender composition of party lists in European Parliament elections https://t.co/lTkyIiVIvp

[BLOG] #EU: Looking into the relationship b/w #PoliticalParty nominations & #women’s representation https://t.co/tehZW9k5na @democraticaudit

“Recruitment procedures shape the gender composition of party lists in European Parliament elections” https://t.co/8CDlRX1lWX

Ever wondered how MEPs are elected to the European Parliament? https://t.co/lZ6BJvrpQ3 @democraticaudit

Our post @democratic:#Recruitment procedures shape #gender composition of party lists in #EP #elections.Have a look https://t.co/cFwE4RTxkC

Recruitment procedures shape the gender composition of party lists in European … – Demo… https://t.co/Fa9iq5jxLv #HRLiveNews #recruit

Recruitment procedures shape the gender composition of party lists in European Parliament elections https://t.co/AQn2lgFcJ5

Recruitment procedures shape the gender composition of party lists in European Parliament elections https://t.co/PKkCHiqRfv

Recruitment procedures shape the gender composition of party lists in European … – Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/JQ6HcJrKhr

Interesting post on ‘Recruitment procedures shape the gender composition of party lists in EP elections’. https://t.co/OAYWLKZibz

Recruitment procedures shape the gender composition of party lists in European… https://t.co/umrdHDEnJd https://t.co/SrALvcYWxv