How can we get more young people voting in elections? Start by abandoning the myth of ‘politically alienated youth’

The UK has the widest gap in voter participation between older and younger citizens in the OECD. Many argue, that despite this, millennials and young people in general are not alienated from politics, but that they are engaged to an extent, but not necessarily in traditional ways. Stuart Fox argues that in order to get young people more engaged, confronting the issue head on will be required.

Credit: David Shankbone, CC BY 2.0

It is fashionable to argue that when it comes to electoral politics today’s young people – the Millennials – are an alienated generation. They are not, the argument goes, politically disengaged, but rather their perception of the democratic process as something alien to them, that they cannot influence, or that they do not feel a part of prevents them from expressing their interest in political issues through it. This is said to explain, their reluctance to vote in elections, their passion for alternative forms of political expression, and even trends like ‘Corbynmania’.

This conventional wisdom dominates academic thinking, policy-making and public debate about how and why young people engage with politics. It has become interwoven with ethical disputes of how we should view young people and their limited electoral engagement: to call young people ‘politically alienated’ implies that they are victims of the failures of our political elites, while to say that they are politically apathetic is associated with blaming them for their lack of participation and ‘letting politicians off the hook’.

The academic research which underpins this conventional wisdom, however, is problematic because it pays so little attention to defining what ‘political alienation’ is. The term is instead used as a way of summarising negative attitudes expressed by Millennials towards politicians, political parties, or the political system more broadly. The question is whether the Millennials are found to be unusually alienated from politics once we develop a clear and coherent idea of what ‘political alienation’ is.

We can find such a conceptualisation in previous literature on political alienation itself, originating in the study of American students protesting against their government and political system in the 1960s. By updating this literature so that it is applicable to modern Britain, we get a clear idea of what alienation from the formalised political process of British democracy actually is. At heart, it refers to an individual (who is interested in politics) feeling estrangement from the processes, institutions, or actors of formal British politics (e.g., parties, elections, MPs, etc.), with clear behavioural consequences.

It could lead to them refusing to participate in the political process (such as refusing to vote), supporting non-mainstream parties who challenge the status quo (such as UKIP or the Greens), or seeking alternative means of political expression (such as protest or political consumerism). This alienation need not, however, manifest in the same way for all people; there are three dimensions of political alienation which represent how it might be apparent:

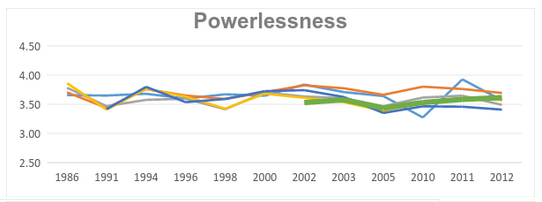

- Powerlessness, in which the individual feels that they have no power to influence the political process

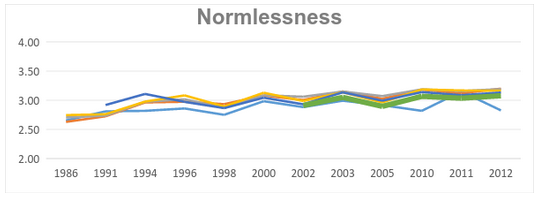

- Normlessness, in which they do not trust that the norms, rules and conventions which govern fair and just political interaction are being adhered to

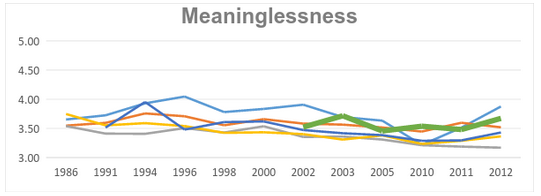

- Meaninglessness, in which they feel that they lack the knowledge and understanding of the political process to meaningfully interact with it

The figures shows several graphs identifying how the Millennials compare with older generations in the British electorate in terms the three dimensions of alienation, using data from the British Social Attitudes survey. The initial impression is that the Millennials aren’t hugely different from the older generations. That said, they do not stand out for being unusually alienated from politics, but – in terms of powerlessness and normlessness – for being un-alienated. Looking at powerlessness, the average score on the 1-5 scale for the Millennials between 2002 and 2012 is 3.5; this compares with 3.6 for the 90s, 80s and 60s-70s generations, and 3.7 for the Post-War and Pre-War generations.

The normlessness data shows a clear trend of rising alienation throughout the electorate since the 1980s, but within this a distinct lack of alienation among the Millennials compared with the older generations (except, on occasion, the Pre-War). The meaninglessness data does not suggest that the Millennials are un-alienated compared with their elders, but nor does it show that they are alienated either. When it comes to their faith in their ability to influence the political process, and in the integrity of that process, the Millennials are the least alienated generation in the electorate, while being quite typical for their faith in their knowledge of the political system.

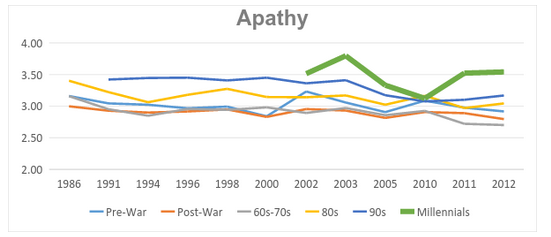

The story is quite different, however, for political apathy (the fourth graph on this page). Here, it is clear that not only did the Millennials enter the electorate with a typically higher level of apathy towards electoral politics than their elders, but they continued to express higher average levels of apathy throughout the series (except for around the 2010 election). Far from being a highly engaged, politically alienated generation, the Millennials are the most apathetic generation in the electorate when it comes to formal and electoral politics, who at the same time feel unusually confident in both the integrity of the British political process and their ability to influence it.

This has clear implications for efforts to get more young people voting in elections. The normative desire to see the Millennials as a politically alienated generation driven away from politics by the failure of political elites must be abandoned. Not only is it logically incoherent (will politicians be credited with the low levels of alienation exhibited by today’s young people?), but it discourages discussion about how we can address the issue of declining interest in politics among young voters. The focus needs to switch to considering why new generations are not developing the same levels of interest in politics as their parents and grandparents, and to what we as a society can do to provide new sources of political information and stimuli for young people to engage.

Proposals such as introducing online voting, or communicating more political information online, are unlikely to be successful because they assume that more young people will engage with the same processes and institutions in which they have less interest than previous generations simply as a result of them bring presented in a different way. Similarly, lowering the voting age without providing new sources of political stimulus and information would most likely simply give more young people the chance to join the many 18-24 year olds who do not vote.

More attention should instead be paid to enhancing civic and political education in schools, and providing young people not only with political information but the chance to participate in the politics of their communities, and to debate local and national political issues. This could provide the information, stimulus, support and opportunity for young people to get into the habit of actively participating in political processes at a young age (and lowering the voting age to 16 alongside such a reform may mean that the policy has a greater chance of success).

Whichever policies are pursued, however, the key point is that they must recognise that the objective is to address the fact that Millennials are the most apathetic generation in the history of British survey research – as well as the least politically alienated – if they are to have any chance of reversing the trend of declining electoral engagement among young people.

—

Data Source: British Social Attitudes Survey 1986 – 2012. More detail on data and analyses available from author on request.

Note: This post gives the views of the author, and not the position Democratic Audit UK, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting.

—

Dr. Stuart Fox is Quantitative Research Fellow at WISERD and Cardiff University. His academic profile can be found here.

Dr. Stuart Fox is Quantitative Research Fellow at WISERD and Cardiff University. His academic profile can be found here.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

How can we get young people voting? Start by abandoning myth of ‘politically alienated youth’, writes @stuarte5933 https://t.co/jU7QSg5Cwm

How can we get more young people voting in elections? | Democratic Audit UK

https://t.co/svygGDdMxT

RT @WISERDNews: .@stuarte5933 asks “How can we get more young people voting in elections?’ https://t.co/oi1qI8eKnp @LSEnews #YoungVoters

We need to stop wishing young people were alienated from politics because we think they should be:https://t.co/5Il4wFEMV4

Interesting new blog from @democraticaudit on political engagement and millennials–it’s apathy, not alienation. https://t.co/yi6Ftop67C

How can we get more young people voting in elections?Start by abandoning the myth of ‘politically alienated youth’ https://t.co/2t1v54BXR3

Dr Fox’s argument is surely right, if dramatically inconvenient. The last three paragraphs represent possibly the only occasion on which I have seen a commentator address the real issues of political apathy among the young. Too often, arguments drift off into mind-numbing treatises about online voting and systems, along with calls for more (powerless) bodies to be set up that they can all vote for. As if this would magically transform engagement.

The argument is sound, but it often appears that the state does not in fact really want this type of engagement – it appears to be preferred that new voters (and to some extent those up the age scale as well, taking their apathy with them) do NOT turn out or have an interest, even if the political class is expressing mock concern about it.

And there is one awkward situation in this – in Greece, a number of surveys showed that, following the volte-face adoption by Syriza of ‘neo-liberal’ austerity policies and the perceived betrayal of its supporters, many of whom were/are young, the one age group where the far right neo-fascist Golden Dawn has suddenly become the most popular party is…the 16-21 year olds. It actually lead the other ‘main 3’ in polling of the group.

A must read article about abandoning the myth of ‘politically alienated youth’ https://t.co/nD3b9Be9lx

RT @philipjcowley: How can we get more young people voting in elections? Start by abandoning the myth of ‘politically alienated youth’:

htt…

RT @LSEPubAffairs: How can we get more young people voting in elections? Start by abandoning the myth of ‘politically alienated youth’ http…

RT @democraticaudit: How can we get more young people voting in elections? Start by abandoning the myth of ‘politically alienated youth’ ht…

How can we get more young people voting in elections? https://t.co/Bjb345cyAG

RT @stuarte5933: Parties going for the ‘alienated youth’ vote always fail to mobilise it – because most aren’t politically alienated: http:…

Civic & political educatn in schools is key to engaging youth in elections, says @stuarte5933 in @democraticaudit: https://t.co/cCZ1Us0M93

How can we get more young people voting in elections? Start by abandoning the myth of ‘politically alienated y… https://t.co/ii8dezkP9e

How can we get more young people voting in elections? Start by abandoning the myth of ‘politically alienated youth’ https://t.co/7cPoFgBgWF

How can we get more young people voting in elections? Start by abandoning the myth of… https://t.co/GrL7IdYMfH https://t.co/dFe63GGwqw