Parties should choose their leadership team with gender balance in mind

The new Leader of the Labour Party, his Shadow Chancellor, Shadow Home Secretary, and Shadow Foreign Secretary are all men, as is the party’s candidate for Mayor of London. Sarah Childs and Meryl Kenny argue that the mechanisms to ensure greater gender representation are available for any political party which seeks to achieve gender process through its allocation of positions.

The new Labour leader, deputy leader, and both candidates standing for Mayor in London and Bristol: all male. And this from a party whose parliamentary benches are more than 43 percent female and, in Bristol, where all its MPs are women. The newspapers and social media, not unexpectedly, were quick to question the party’s commitment to gender equality. Whatever you think of revaluing the education and health brief (and there’s a lot to be said for it), the absence of not one woman from the traditional top offices of state invited criticism. Some of this was no doubt right-wing commentators finding yet another reason to be critical of Labour’s new leader.

But the feminist criticism was more substantive: a longstanding worry that leftist politics often has too little room for gender equality in policy and personnel terms. Against such criticism, the counter argument: given the number of women candidates standing, party members had ample opportunity to vote for a woman. In short, Corbyn was the preferred candidate, his sex notwithstanding.

Why does it matter? The question of who occupies the ‘top jobs’ in politics is more important than ever – with British politics and media coverage increasingly focused on party leaders at the expense of parties, candidates and policies. Yet, while some cracks have been made in the political glass ceiling – most notably in Scotland, where the three largest parties in the Scottish Parliament are all led by women – women have been few and far between as party leaders at Westminster. This reflects wider comparative trends, where the general rule has been ‘the higher, the fewer’ – in other words, the more powerful the position, the less likely it is to be filled by a woman.

Can parties committed to gender equality be content when women are under-represented or marginalised? The continuing under-representation of women in the top jobs at Westminster sends powerful symbolic messages about who is ‘fit to lead’ (and who is not). Who gets to be perceived as a credible leader? Who looks like an election winner? Who is regarded as authoritative? Against the ‘male-politician-norm’ the ‘woman-politician-pretender’ is likely to be find wanting – recall what they used to say about Harriet Harman until, on taking on the deputy leadership and Leader of the House, many former critics changed their views (As a Professor of Politics admitted in private). Gender equality in political leadership also has potential substantive effects. Studies, for example, have found that having more women in party leadership positions has a positive impact on women’s representation; while others find that as the number of women in leadership roles rises, parties are more likely to include social justice issues in their party platforms.

What can parties do to address the under-representation of women at the top? Just like (good) legislative quotas ensure parties’ candidate selection processes become fair, gender-balanced leadership rules ensure that party leadership positions reflect gender equality. Drawing on previous proposals made by the PSA Women and Politics Group, we identify four ways in which the principle of a sex-balanced party leadership might be achieved, each with its advantages and disadvantages.

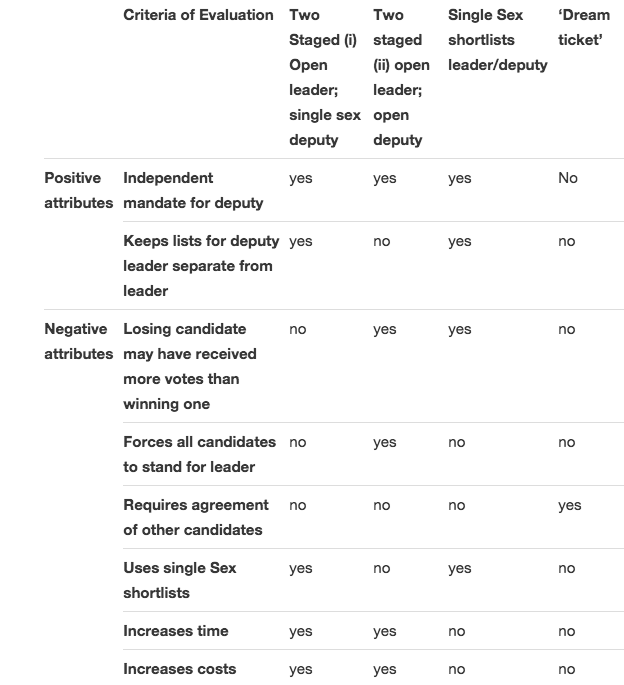

Table 1: Models for Sex-Balanced Party Leadership: Advantages and Disadvantages

(1) Two-round election (i) Open leader, single sex deputy shortlist: election of leader first; election of deputy via a single sex shortlist (of the opposite sex) following the election of leader

In round one the winning candidate becomes party leader; from a shortlist comprised of candidates only from the opposite sex to the newly elected leader, the top ranking deputy candidate in the second round of elections is duly elected.

Advantages: most importantly, it ensures an independent mandate for the deputy; keeps separate candidacies for leader and deputy (we do not assume all candidates would wish to stand for both); candidates do not require the ‘agreement’ of other candidates to put themselves forward.

Disadvantages: extends timing of the selection as it involves two rounds; will increase costs due to two election times; critics of single sex lists will not be predisposed towards it; women might be less likely to be elected as leader – although this is not a given.

(2) Two staged election (ii), where top ranking man/woman proceed to the second round to determine leader/deputy position

Advantages: at each stage voters must vote for both a male and a female candidate (should both stand at both rounds), or the ballot paper will be deemed as spoilt; avoids criticism of explicit single sex shortlists; candidates do not require the ‘agreement’ of other candidates to stand; might be said that both leader and deputy have mandates given they both participate in both elections; ensures that women and men candidates take part in both rounds.

Disadvantages: Forces all candidates to stand for leader even if they only wish to be elected as deputy leader; as with model (1) there are time and likely financial costs; most importantly, it is possible that the number of votes for the candidate who becomes deputy in the second round may be less than the second ranking candidate of the opposite sex in the first round, thereby reducing their mandate/legitimacy.

(3) Single sex shortlists for both Leader and deputy

There would be two sets of candidate lists: one male and one female for the leader; one male and one female only for the deputy. The top ranking leadership candidate wins; the top ranking deputy of the opposite sex wins.

Advantages: single election time; candidates can stand for both leader and deputy leader.

Disadvantages: most importantly, the number of votes for the ‘winning’ deputy may be less than the total number of votes cast for the ‘top ranking’ deputy candidate from the same sex as the newly elected leader.

(4) ‘Dream ticket’

Prospective leader/deputy come together and offers themselves as a slate

Advantages: ballot is at a single time point; provides for a cohesive leadership team; can combine, but does not guarantee that the leader/deputy reflects intra-party differences.

Disadvantages: most importantly, it removes the independent mandate from the deputy; may reduce the likelihood of leadership team reflecting differences across the party; may position women as the deputy more often than as leader, although this is not a given.

Which model is the best? Our preference is for Model 1: there is an independent mandate for the deputy plus a real opportunity for a woman to be elected as leader. Moreover, it has the distinct advantage over Model 2 of keeping separate candidacies for leader and deputy – we do not assume all candidates would wish to stand for both leader and deputy. What should the parties do? A commitment to the principle of gender equality in political leadership is one can easily sign up to, forthwith. And with a choice of election procedures from which they can choose, there’s no way they can say that they do not know how to deliver sex balanced leadership.

—

Note: this post originally appeared on the Bristol University policy blog site, and a version of it also appeared on the Fawcett Society website. It is reposted with the permission of one of the authors. It gives the views of the author, and not the position Democratic Audit UK, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting.

—

Sarah Childs is Professor of Politics and Gender at the University of Bristol

Sarah Childs is Professor of Politics and Gender at the University of Bristol

Meryl Kenny is Lecturer in Politics (Gender) at the University of Edinburgh, and Co-Convenor of the PSA Women and Politics Specialist Group. She tweets from @merylkenny.

Meryl Kenny is Lecturer in Politics (Gender) at the University of Edinburgh, and Co-Convenor of the PSA Women and Politics Specialist Group. She tweets from @merylkenny.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Note: this post originally appeared on the Fawcett Society website, and a version of it also appeared on Democratic Audit UK. […]

occhiali oakley brescia

Thank you for another great article. The place else may just anyone get that kind of info in such an ideal approach of writing? I’ve a presentation next week, and I am at the search for such info.

[…] Parties should choose their leadership team with gender balance in mind. […]

Parties should choose their leadership team with gender balance in mind: The new Leader of the Labour Party, h… https://t.co/PKtXjB8kK9

Parties should choose their leadership team with gender balance in mind https://t.co/o0IySqHPik

Parties should choose their leadership team with gender balance in mind https://t.co/Cdlw2e7LSR https://t.co/suwoQ1030U