Tokenism, or a new dawn for gender equality? Exploring the implications of Jeremy Corbyn’s majority-woman Shadow Cabinet

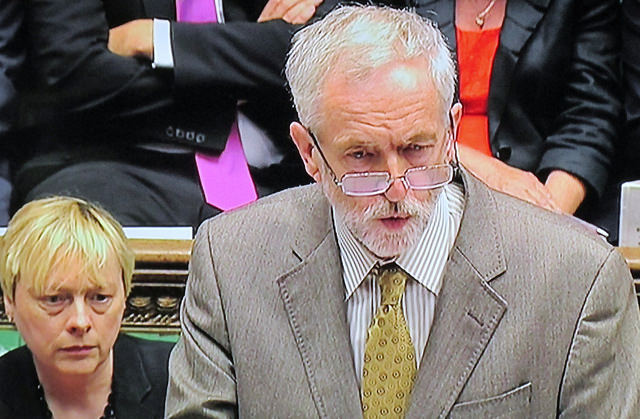

Jeremy Corbyn’s Shadow Cabinet raised a few eyebrows when it was revealed that there would be no women among the most senior positions, despite the subsequent appointment of Angela Eagle as Shadow First Secretary of State. Despite this, the Shadow Cabinet is Britain’s first majority female Cabinet or Shadow Cabinet, but, asks Dee Goddard, who actually holds the decision-making power?

So the Labour party doesn’t have a female leader. Or a female deputy leader. Or a female London mayoral candidate. But it does have Jeremy Corbyn and his shadow cabinet that contains more women than men.

Back when Corbyn looked unlikely to win the leadership election, he made a pledge that the shadow cabinet would be 50% female and that the Labour party would tackle gender inequality head on.

And Corbyn has met his pledge of a 50% female shadow cabinet. In fact, he bettered it, appointing 16 women and 15 men.

Women MPs were appointed to various important roles on the shadow front benches. Angela Eagle becomes shadow business secretary and shadow first secretary of state, Lisa Nandy as shadow energy secretary, Lucy Powell takes the education portfolio and Diane Abbott as shadow minister for international development.

Indeed it seems that more women have been appointed to shadow ministerial posts than ever before.

But the gender balance does not permeate throughout the cabinet hierarchy. Corbyn has handed the four top shadow cabinet posts (leader, shadow chancellor, foreign secretary and home secretary) to men.

The fact that the public, and political commentators, have highlighted the lack of women at the very top of Corbyn’s Labour party has demonstrated a shift in the electorate’s expectations about the gender balance of the top posts in political parties.

Shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, has defended Corbyn’s appointments by arguing that the hierarchy of the cabinet is an artefact of the 19th century. He has suggested that the health and education ministries (which have been allocated to Heidi Alexander and Lucy Powell) are top jobs under Corbyn’s leadership, as they represent the services that people interact with on a day-to-day basis.

Under Corbyn’s leadership, this may be the case. But he will have to work to persuade those concerned about the representation of women at the top of the Labour party that the old hierarchies of government will not persist. This will mean media exposure for a wide range of ministers (not just the shadow chancellor) and giving his shadow ministers more command over the parliamentary floor. Shifting standards In 2008, David Cameron, as leader of the opposition, set an objective that one third of his Cabinet would be female by the end of his first term in office. This was largely perceived as an attempt to decontaminate the “nasty” Conservative brand, and appeal to women voters. And indeed, before the resignation of Maria Miller as secretary of state for culture, media and sport, Cameron’s cabinet was one third female. Famously, none of the eight Liberal Democrats appointed by Nick Clegg to the coalition cabinet were women.

In the cabinet appointed after the 2015 general election, exactly a third of all ministers permitted to attend cabinet were women – although they made up just 20% of those appointed as ministers of state – the highest rank of junior minister.

The tendency to appoint women to the most public posts while they remain under-represented in junior positions could be seen to show how party leaders are held to account on their pre-election pledges about women’s representation, even if they aren’t committed to promoting women at all levels of the party.

Corbyn has committed to promote women at all levels of the Labour party, and the early years of his leadership will test his commitment to the progression of women throughout the party.

Party leaders across the political spectrum in the UK and throughout Europe are under increasing pressure to appoint more women to the most high-profile political posts. As the most visible public representatives of the party, ministers and shadow ministers are the symbolic face of the party, and their demography shapes the electorate’s perception of the party and its leader.

Best on the left?

Whether driven by an attempt to suggest a feminisation of the party’s agenda or more simply to show that the party is not “pale, male and stale”, party leaders are aware of the public’s concern about the gender balance of the cabinet.

This is especially the case for left-wing parties across Europe. Voters expect these groups to be progressive on gender issues.

In 2004, the left-wing Spanish prime minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero, appointed a majority female cabinet and a seven-months-pregnant defence minister. This was a clear move to signal his commitment to promoting women in the party, and the feminist left-wing agenda.

This ideology factor also explains the backlash against Corbyn’s appointments. As a socialist Labour leader, Corbyn was expected to be amongst the most progressive in his shadow cabinet appointments.

For the women who backed Corbyn during his leadership campaign, the lack of women in the core team of the shadow cabinet is disappointing. Especially after claims have emerged that Angela Eagle’s additional role as shadow first secretary of state was announced as a way to resolve the “women row” arising from Corbyn’s early appointments.

It will be up to the Labour leadership in the upcoming weeks to determine how much exposure the women in the shadow cabinet receive. It is clear that there is a public appetite for the representation of women in the most high-profile roles of Labour’s shadow cabinet. If Corbyn believes that he has given the real high-profile jobs to women, he’ll need to prove it to the media and in the House of Commons.

—

This article was originally published on The Conversation. It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit UK. Please read our comments policy before posting. ![]()

—

Dee Goddard is a PhD Candidate at the University of Kent

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Tokenism, or a new dawn for gender equality? Exploring the implications of J. Corbyn’s majority-woman Shadow Cabinet https://t.co/z0TI24CFKe

[…] when women do have equal rights and are getting into more and more positions of power (with even a female-majority Labour shadow cabinet), is the exclusory “advocacy of women’s rights” entirely […]

Tokenism,or new dawn for gender equality?Exploring the implications of Jeremy Corbyn’s majority-woman Shadow Cabinet: https://t.co/Z0uY04Lfe8

Tokenism, or new dawn for gender equality?Exploring the implications of Jeremy Corbyn’s majority-woman Shadow Cabinet:https://t.co/qyyCAC6um0

[…] Democratic Audit UK Tokenism, or a new dawn for gender equality? Exploring the implications of … […]

Tokenism, or a new dawn for gender equality? Exploring implications of Jeremy Corbyn’s majority-woman Shadow Cabinet https://t.co/WldJEOVozy

Gender balance isn’t just about numbers, says @DeeGoddard9. https://t.co/UAMh8OAqzu Women need to be in top posts not just in more posts.

“The fact that the public… highlighted the lack of women at the very top of Corbyn’s Labour party has demonstrated a shift in the electorate’s expectations about the gender balance of the top posts in political parties.”

“Voters expect these groups to be progressive on gender issues.”

“For the women who backed Corbyn during his leadership campaign, the lack of women in the core team of the shadow cabinet is disappointing.”

Evidence for any of these claims? I think back to a little before his landslide victory, that many commentators were proclaiming that women were having none of it, that either Yvette Cooper or Liz Kendall was the feminist choice, and that no woman could vote for Corbyn given his (in actual fact woman-led) policy vis-a-vis women-only carriages on public transport, and yet the polls turned out to show that not only did he clean up among women (while Cooper and Kendall trailed pitifully behind) but his support was actually substantially skewed towards women.

Tokenism or a new dawn for gender equality? The implications of Jeremy Corbyn’s majority-woman Shadow Cabinet https://t.co/WldJEOVozy

Tokenism or a new dawn for gender equality: exploring the implications of Jeremy Corbyn’s majority-woman Shadow Ca… https://t.co/mmWCtDillz

Tokenism or a new dawn for gender equality: exploring the implications of Jeremy Corbyn’s… https://t.co/Eap5CEPc6o https://t.co/WkYIXI62iH