Evidence from the United States shows that the gerrymandering of district boundaries is not necessarily a cause of political polarisation

In the United States, boundaries for the House of Representatives and many states are decided by the membership themselves rather than an independent commission (as is the case in the UK and many other European democracies). Reformers in the United States argue that the commission based model is superior and that it would act as a counterweight to political polarisation, but Josh Ryan presents evidence from the US that shows that this isn’t necessarily the case, and that independent commissions are not accountable to the voters.

In the United States House of Representatives, similar to the UK Parliament, members represent small geographic constituencies, called districts, and must stand for re-election every two years. The number of members of the House is fixed at 435, and as of the most recent census, every district contains about 710,000 Americans. Some districts, in large cities such as New York or Chicago, are only a few miles across, while others encompass entire states. Population changes within districts require boundaries be redrawn or redistricted every ten years, a process which has recently become embroiled in controversy due to the perception that it is partly responsible for the high level of ideological polarization in the House of Representatives.Forty years ago, overlap existed between the Republican and Democratic parties. In the time since, the parties have diverged dramatically, with Democrats becoming much more liberal, and Republicans much more conservative. There is so little room for compromise between the two parties that Congress is now referred to as the “broken branch” and recent congressional crises over mundane tasks have made Congress less popular among the American public than cockroaches, traffic jams, and used-car salesmen.

It is unclear why polarization has increased, but many observers have cited redistricting as one important cause. The Constitution leaves the task of creating district lines to the states, and most give the elected officials of the state legislature the power to redistrict. The members of the majority party in the legislature, who themselves are strong partisans, use sophisticated computer technology to create districts which contain a majority of their own party voters. The resulting safe districts, the argument goes, create ideologically extreme members of Congress who have little reason to appeal to voters of the other party or even centrists, thus creating polarization in the House of Representatives.

The solution, supported by some academics, the media, non-profit groups, and even some elected officials, is to take the redistricting process out of the hands of state elected officials and instead delegate it to non-partisan citizen commissions, made up of citizens who are not elected, but appointed by the governor or some other official. These commissions are not supposed to take politics into account when drawing districts and instead, only consider “fairness”, “communities of interest,” certain legal requirements regarding the racial composition of districts, and geographic compactness.

Using non-partisan or independent commissions has to proven to be popular in the states. Polls show most Americans support them and a number of states, including Iowa, Arizona, California, and Colorado have adopted these commissions with strong public support. But, the question remains as to whether non-partisan or independent commissions draw districts differently than legislatures, in a way that reduces polarization.

In a recent article, my co-author and I compared legislature-drawn districts to commission- drawn districts using two outcomes: the percent of voters in each district who voted for the Republican and Democratic presidential candidates (called district partisanship), and the ideology of the House members from each district. Presidential vote share is a common way of measuring the partisanship of a district as the presidential election is highly partisan and dis- tricts can be compared to national averages. For example, if the Republican candidate won 50% of the votes in the nation, but 80% in the district, it is clear the district is more partisan (in a conservative direction) than the nation as a whole. The ideology of members is taken from a nationally recognized measure which puts individual congress-people on a numeric scale from most liberal to most conservative. If independent commissions reduce partisan redistricting, we would expect to see districts where the presidential vote looks more like the nation as a whole, on average, and districts where the elected member of the House of Representatives is closer to the middle of the ideological scale.

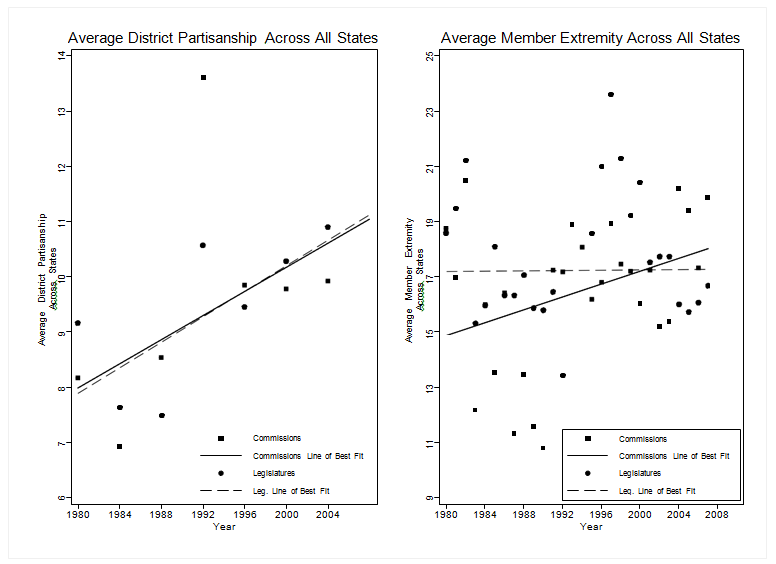

In fact, controlling for other factors such as the number of districts in the state, our research finds no difference between legislature and commission drawn districts from 1980 through the 2000s. On average, districts drawn by commissions are just as partisan in presidential election voting as those drawn by legislatures, and produce the same level of ideological extremity among members of the House. Across the entire time span, states with legislature-drawn districts had a district partisanship score of 9.95, while states where commissions created districts had a partisanship score of 9.67, a trivial, and statistically insignificant difference. The average member extremity in legislature redistricting states was 16.39 while in commission states it was 16.24, also a very small and non-significant difference. As the graph demonstrates, district partisanship has steadily increased from 1980, but there are no discernible differences between states with commissions and states with legislatures (left panel). The right panel shows that states with commissions had, on average, less extreme members throughout the 1980s, but as polarization increased in the late 1990s, there is no difference between legislature and com- mission states. We conclude that commissions do not achieve their goal of drawing “fairer” districts, and will not have an effect on the level of polarization in Congress.

Why don’t commissions produce different outcomes from state legislatures? First, despite the rhetoric for “fair” districts, no one actually agrees on what fairness means in the context of redistricting. Some feel that districts should be geographically compact, but in the United States, where you live and what you think are increasingly intertwined. Citizens in cities tend to be much more liberal than those in rural areas, so to ensure an even number of Republicans and Democrats, districts would have to capture small parts of large cities and rural areas. But, this would produce very strange shaped districts and pit rural and urban interests against each other in the same district. This is especially problematic when one considers that cities are multi-ethnic and multi-racial and tend to elect a diverse group of congress-people, while rural areas tend to be predominantly white. In short, legislatures and commissions may simply be too constrained by the geographically segregated nature of the American public.

Figure 1: Average District Partisanship and Member Extremity in Commission and Legislature Redistricted States Across Time

If commissions do not actually achieve their goals, there is an important reason we should prefer legislature-drawn districts. Legislatures are a democratic institution with popularly elected officials who are accountable to voters. Rather than subjecting the redistricting process to the give-and-take of the legislative development and passage process, commission-based re districting puts the power in the hands of only a few individuals who are not subject to voter approval through elections.

Legislatures are inherently partisan in nature, but they derive their legitimacy from the electoral process and the marketplace of ideas. These arguments have not yet dampened the enthusiasm for commissions, but perhaps it is better to allow lawmakers to debate notions of re-districting “fairness” in a public forum rather than allow an appointed set of unknown officials to make their own decisions in private.

—

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Josh Ryan is Assistant Professor of Poltical Science at Utah State University.

Josh Ryan is Assistant Professor of Poltical Science at Utah State University.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Evidence from the United States shows that the gerrymandering of district boundaries is not necessarily a cause of… https://t.co/ymCPiEWoSI

Evidence from the United States shows that the gerrymandering of district boundaries is not necessarily a caus… https://t.co/mxeyp0k3Kg

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/mega-profix-software-review-download-now-pravin-kumar

https://nytransguide.org/mega-profix-review/

List building is about much more than just getting a huge list of names and emails. You’ve got to nurture your list in order to make your subscribers responsive. First of all, only targeted subscribers are going to be responsive. In other words, you’ve got to get subscribers who are actually likely to buy from you, here’s how:

Evidence from the United States shows that the gerrymandering of district boundaries is not… https://t.co/9YsYah5hBf https://t.co/tFDZLxDMCp