There is a need to develop both a victim-led and victim-centred approach to dealing with the legacy of Northern Ireland’s violent past

The conflict in Northern Ireland is now largely at an end, with violence only occurring infrequently. In its aftermath, argue John D. Brewer and Bernadette C. Hayes, it is important to develop an approach which is both led by, and centred around, the victims of conflict on both sides.

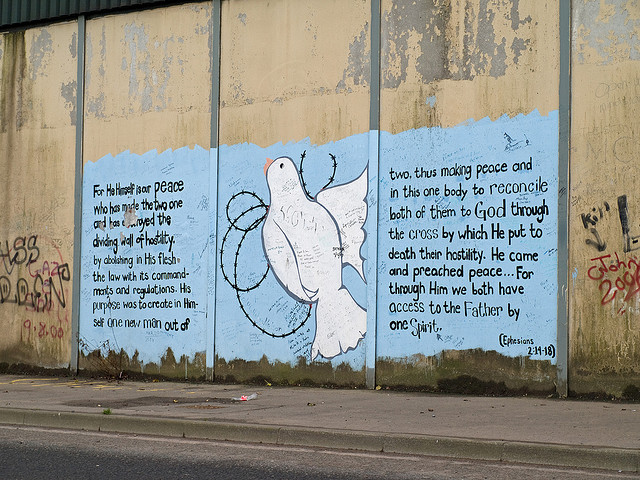

Credit: Shaun Dunphy, CC BY SA 2.0

No matter how successful the introduction of new governance structures and the institutional reform of politics, societies emerging out of conflict are left with a series of legacy issues that are important to reconciliation and healing in society. If not adequately addressed, these issues can destabilise the democratic gains made during the peace process. Legacy issues concern specific policy questions like amnesty for former combatants and the range of victim and survivor policies, but also broader matters like dealing with the past, and the meaning of values like truth, justice and forgiveness.

These legacy issues rarely surface in the immediate aftermath of a negotiated settlement for the euphoria and expectations at the ending of conflict side line them. The paradox of legacy issues is that they emerge only sometime later, in the long and difficult process of learning to live together once the violence is largely over, when people’s expectations of change have been disappointed or re-evaluated in the light of experience, and the peace process seems to bounce along at the bottom. This is precisely when the peace process is at its lowest ebb, a point where post-conflict societies come to realise that learning to live together is not automatic and does not follow naturally once the violence has ended.

At this point of lowest ebb, legacy issues come to assume almost as much importance in political debate as the original conflict itself, making discussion of the morality of the conflict a route into revisiting the terms of the settlement that ended it. Legacy issues can thus become politicised and function as the main arbiter of the future, determining the confidence people have in the whole settlement and in the likelihood of people learning to live together. Therefore, the legacy issues of violence that were once parked while negotiators dealt with the more immediate task of ending the violence, come back to haunt the negotiation process and fuel opponents’ accusations of it being a ‘dirty peace’.

Managing the problems that legacy issues cause is therefore vital to stabilising the democratic reforms that introduced the new governance structures, as well as to progress in healing and reconciliation in society.

There is no way of escaping these legacy issues, since they emerge inevitably in the course of a peace process at the point when memory of the violence recedes and debate about the morality of the conflict supersedes that about the conflict itself. If they cannot be avoided, what is important is that they are managed.

Truth recovery is advocated as the primary management process for this. But rarely are the views of victims themselves canvassed for how to deal with the past. In an article recently published in The British Journal of Politics and International Relations (see here), we address this omission by providing the first systematic study of victims’ views on how to deal with a violent past. Using Northern Ireland as a case study and focusing on the three main religious groupings – Protestants, Catholics, and the non-affiliated – within this society, the data is based on a nationally representative sample of the adult population which was collected in 2011 and funded by our Leverhulme Trust-funded research programme ‘Compromise after Conflict’.

Attitudes on how to deal with the past were operationalised in terms of victims’ views concerning six approaches to dealing with the legacy of Northern Ireland’s violent past. These included formal truth recovery mechanisms such as a truth commission, more police investigations and prosecutions, and more public inquiries. In addition, views on informal mechanisms were also included—such as public apologies from those who did wrong and initiatives within communities to help people come to terms with the past—as well as focused support for victims.

Results show that there is overwhelming agreement amongst all victims that victims should be supported with focused initiatives. There is also very strong support across the communal divide for unofficial approaches, such as community-based local initiatives. This is not the case when formal truth recovery mechanisms—such as truth commissions and public inquiries—are considered. Here support among victims remains either lukewarm (truth commissions) or extremely limited (more public inquiries) at best. Moreover, there are also some stark differences between the various religious groupings particularly in relation to this issue, with victims from within the Protestant community as well as among the non-affiliated, being significantly less likely to endorse such formal truth recovery initiatives than their Catholic counterparts.

The results also show that while both perceptions of victimhood and general attitudes towards the past are the key determinants of victims’ views in relation to truth recovery mechanisms, their effects differ across the various religious groupings. While perception of victimhood is the key predictor of opinion within both the Protestant community and among the non-affiliated, it is general attitudes towards the past which emerges as the major determinant of Catholic views. In fact, more so than any other factor, it is this issue—a hierarchical or restrictive approach to victimhood—which accounts for the lack of Protestant support for the introduction of range of truth recovery mechanisms to deal with the legacy of the past. By contrast, it is general opinions on how to deal with the past, and not perceptions of victimhood, which emerge as the key determinant of Catholic views.

Overall, the results of this investigation point to the need to develop both a victim-led and victim-centred approach to dealing with the legacy of Northern Ireland’s violent past. Such an approach should be a bottom-up initiative, reflecting victims’ priorities and preferences. The results also suggest that a comprehensive package of financial support to meet the material and social needs of victims would be a fruitful and unifying place to start.

Such an approach to the past might help ensure the democratic gains in Northern Ireland do not collapse.

—

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

John D. Brewer is Professor of Post-Conflict Studies at Queen’s University Belfast

John D. Brewer is Professor of Post-Conflict Studies at Queen’s University Belfast

Bernadette C. Hayes is Chair in Sociology and a Professor at Aberdeen University

Bernadette C. Hayes is Chair in Sociology and a Professor at Aberdeen University

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Prof Brewer writes on victim-led and victim-centred approach to dealing with the legacy of NI’s violent past https://t.co/45pjuLIdGN #ISCTSJ

On the need for inclusive victim-led and victim-centred approaches in Ireland -Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/AmTXXDRv07

Developing both a victim-led and victim-centred approach to dealing with the legacy of NI violent past #publicinquiry https://t.co/xJx4zpV6Wi

There is a need to develop both a victim led & centred approach to dealing with the legacy of Northern Ireland’s past https://t.co/3VWjUIL0Kt

There is a need to develop both a victim-led and victim-centred approach to dealing with the legacy of Northern Ir… https://t.co/U9yWRHI1mo

There is a need to develop both a victim & centred approach to dealing with the legacy of Northern Ireland’s past https://t.co/xa0lT4iaXC

On a victim-led and victim-centred approach to dealing with the legacy of Northern Ireland’s violent past https://t.co/6LuFe9CLux

What Northern Ireland needs is victim-led and victim-centred peacebuilding, see @Prof_johnbrewer @ISCTSJ at https://t.co/57UTwfDFUl

There is a need to develop both a victim-led and victim-centred approach to dealing with the legacy of Norther… https://t.co/Ed7MNeqz4w

@Prof_johnbrewer & B Hayes: Need for victim-led & victim-centred approach to dealing with past in N Ireland https://t.co/RqRZf2ljQo

We must develop a victim-led & victim-centred approach to deal with the legacy of Northern Ireland’s violent past https://t.co/a7UJgoP0VO

There is a need to develop both a victim-led and victim-centred approach to dealing with the… https://t.co/2ddID2oLLJ https://t.co/fCqWCaidlo