The ‘Anderson Report’ on surveillance powers does fudge the issues, but its findings should be implemented

David Anderson, a QC, the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, recently published a report on the governments surveillance activities in the wake of the Snowden revelations, which showed a far higher degree of unwarranted data collection than most had previously thought. Andrew Wheelhouse argues that though the report does fudge the issues to an extent, its recommendations should be implemented in order to improve accountability.

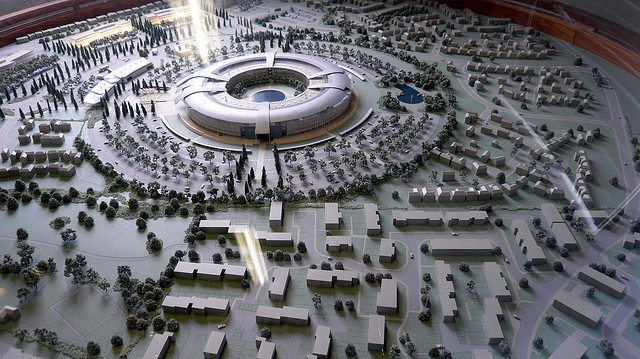

Credit: Cory Doctorow, CC BY SA 2.0

Pressure on the government to reform the use of surveillance powers within the UK has recently ratcheted up another notch. A few months ago the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament (ISC) and the Interception of Communications Commissioner’s Office (ICCO), published reports criticising aspects of the surveillance system (see here). Now David Anderson QC, the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation has published his own report reviewing UK surveillance law in its entirety and making a comprehensive list of recommendations for reform.

At over 350 pages, ‘A Question of Trust’ is a veritable tome, which considers not only UK law, but the law of the other members of the somewhat creepily named ‘Five Eyes’ security network (UK, USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand). As the title suggests, the main aim of Anderson’s proposed reforms is to restore public confidence in the legal framework governing surveillance. He does not advocate curtailing the use of surveillance powers. As someone who was granted unrestricted access to classified material, he is clearly convinced of their value. His report includes 6 anonymised case studies (Annex 9) illustrating the value of surveillance. One case concerned an airline worker who took great pains to conceal his extremist views and whose conviction would have been unlikely without access to bulk data. In another case, it was bulk data and bulk data alone that secured the arrest of one group “literally en route to conducting a murderous attack”.

Such case studies pose a quandary for those opposed in principle to government mass surveillance programmes. How many otherwise preventable terrorist outrages is one willing to endure rather than curtail the surveillance powers available to the state? Would your answer change if one of those attacks turned out to be a 9/11-style ‘spectacular’?

Mr Anderson is clearly troubled by the implications of such thinking. This explains the centrepiece of his recommendations: the replacement of ministerial authorisation of surveillance with judicial authorisation. He recommends that the three existing commissioners be replaced by a new beefed-up body called the Independent Surveillance and Intelligence Commission. ISIC would take over the oversight and auditing functions of its predecessors, and its Judicial Commissioners, who would be serving or retired senior judges, would take over authorisation of all warrants.

There are a host of other noteworthy measures. Like the ISC, Mr Anderson recommends that the mess of current surveillance legislation be replaced with a single Act, which will hopefully be written in comprehensible English. He is sceptical of the proposals in the government’s so-called ‘Snooper’s Charter’ for the compulsory retention of records of user interaction with the internet or of ‘third party data’ (luddite’s guide here), at least until a compelling case is established. There would be a new ‘bulk communications data warrant’ that would limit mass surveillance of the sort seen in the PRISM and TEMPORA programmes to specific operations targeted at individuals outside of the UK.

One of the knock-on effects of the recommendations is that acquiring confidential or privileged information, especially that subject to legal professional privilege, will now be subject to judicial authorisation which should help prevent the sort of embarrassment suffered by the security services in the Belhadj case.

Finally, the tribunal in that case, the Investigatory Powers Tribunal should have an expanded jurisdiction to hear complaints against communications service providers as well as public bodies. There should be a right to appeal from the IPT on a point of law and the tribunal should have the power to rule that future legislative measures are incompatible with the Human Rights Act. It would work in close collaboration with ISIC which would be empowered (subject to restrictions) to notify individuals that they have been the subject of illegal activity and that they may be able to seek redress through the IPT.

The Anderson recommendations, if implemented (a prospect that currently seems unlikely for its central proposal) would be a positive development. It will deliver bigger, meaner regulation and hopefully a statutory framework that normal people have at least a fighting chance of understanding.

Looked at differently the report reflects many of the current trends within contemporary political discourse. Judicial oversight can be seen as a continuation of the outsourcing of political decision-making to judges seen in the rise of the judge-led public inquiry in the UK. The emphasis on rights compliance and legality is also telling. Like the application of the Human Rights Act to active combat zones abroad in cases like Smith v MoD, it allows David Anderson to be Janus, striking a good pose for the civil liberties lobby, whilst securing in large part the capabilities of the intelligence services. It conflates the legal question with the political question. In Smith it was the use of force overseas. Here it is whether the use of mass surveillance in society is justified.

Unlike Smith however, the balance Anderson has tried to strike may well be the right one. What was most shocking about the revelations around PRISM and TEMPORA was the impression of spooks run amok with no independent oversight, rather the notion that they had found new and innovative ways to be engaged in the business of (the horror!) spying. Implementing the recommendations will do a great deal to restore accountability to the system. But whether we like the balance the Judicial Commissioners choose to strike between privacy and surveillance is another matter.

—

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of Democratic Audit UK, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Jordan 7 Bordeaux for cheap

that of an able bodied person. If there are medical injuries, then the safest bet is to contact a

“The ‘Anderson Report’ on surveillance powers does fudge the …” https://t.co/ownZsfjnKE

The ‘Anderson Report’ on surveillance powers does fudge the issues, but its findings should be implemented https://t.co/FvVZ4eccYT

The ‘Anderson Report’ on surveillance powers does fudge the issues, but its findings should be implemented: https://t.co/KfnHh6RoDv

The ‘Anderson Report’ on surveillance powers does fudge the issues, but its findings should be implemented https://t.co/pHzCddCqcn

The ‘Anderson Report’ on surveillance powers does fudge the issues, but its findings should be implemented https://t.co/i49uq2f1PI #Option…

‘The ‘Anderson Report’ on surveillance powers does fudge the issues, but its findings should be implemented’. https://t.co/Q9HYJo4LEB

The ‘Anderson Report’ on surveillance powers does fudge the issues, but its findings should… https://t.co/0shxm5YcyR https://t.co/hblxKUBIdK