Education can provide both the opportunities and capabilities to make active citizens of our young people

The General Election once again showed the extent of yawning divide in terms of political participation between older and younger citizens. James Sloam and Ben Kisby reflect on the extent to which young people (dis)engage from politics. By analysing data from the European Social Survey, they conclude that educational institutions are a vital factor in influencing young people’s levels of disengagement.

Credit: Francicso Osorio, CC BY 2.0

Much attention has been paid by academics and policy-makers in recent decades to declining levels of voter turnout and engagement with traditional political and social institutions in established democracies – from political parties to trade unions to religious organisations. These trends are particularly marked among young people. Nevertheless, a number of authors have, more positively, pointed to the proliferation of youth participation in a myriad of alternative forms of engagement. If we take a broad look at political participation – focussing on what young people are actually doing rather than what they are not doing – it is in fact possible to conclude that the Millennial Generation are at least as politically active as previous generations. In this sense, they continue to have a voice. However, these changes in political and civic engagement raise new questions about inequalities in participation and the nature of political socialisation.1

Young people have increasingly become ‘standby citizens’ who engage from time to time with political issues that hold meaning for their everyday lives.2 In general, they are attracted to intermittent, non-institutionalised, issue-based, horizontal forms of engagement and repelled by the thought of long-term commitment through formal institutions with broader policy goals and entrenched hierarchies. As well as young people’s repertoires of participation having changed, the political arenas in which they operate have also become more diverse, including, in particular, online social networks. The rise of the Internet and new social media has enabled a quickening of political participation that promotes real time engagement in politics and non-hierarchical forms of mobilisation.

Whereas voting is generally considered to be a relatively socially equal political act (at least in Western Europe, this is much less so in the United States), the same, however, cannot be said for alternative forms of engagement, such as signing a petition, joining a boycott, participating in a demonstration, or utilising new social media. Recent research suggests that social inequalities are significantly increased in non-electoral forms of political engagement. Since young people are more likely to engage in these non-electoral forms of participation than older cohorts, our concern is with whether this translates into political participation that is less socially equal for young Europeans, and we are interested in what role education might play in mitigating these inequalities. The literature on civic and citizenship education suggests that personal efficacy plays a key role in actualising young people’s politics, whereby the political literacy, democratic skills and self-confidence of young citizens are of fundamental importance.3

Drawing on the most recent data available from the European Social Survey (ESS), which is undertaken every two years, we have found that being in education significantly boosts young people’s civic and political participation helping neutralise the differences between high-income and low-income groups with regard to such participation.

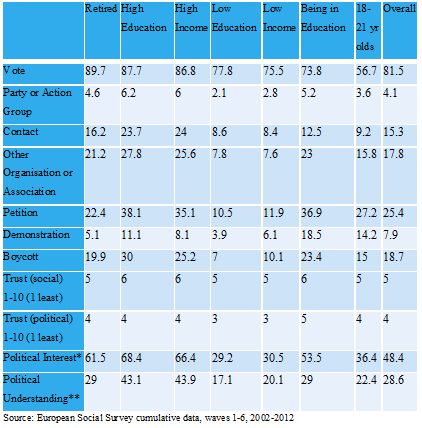

Chart 1: Political participation in the European Union (EU 15)

Table 1 shows that young people, here 18-21 year olds, are less engaged in traditional, electoral politics (especially voting) than the general population, but as engaged in other forms of participation. Being in education clearly matters a great deal because those in education are more active than the general population in all forms of participation except voting and contact (although the gap here is not that large) and have higher levels of social and political trust.

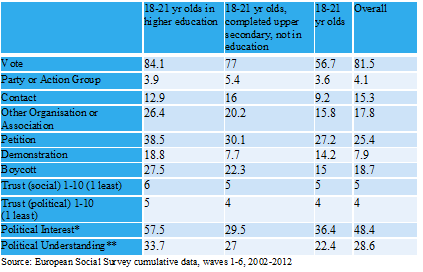

Chart 2: Political participation of 18-21 year olds in the EU

Table 2 shows that 18-21 year olds in higher education have similar levels of engagement in electoral politics as the mean figure for all ages, but are much more likely to engage in all other forms of participation than the general population (see also Table 1). They also have higher levels of social and political trust than the general population and are much more likely to sign petitions, participate in demonstrations and join boycotts than 18-21 year olds not in higher education.

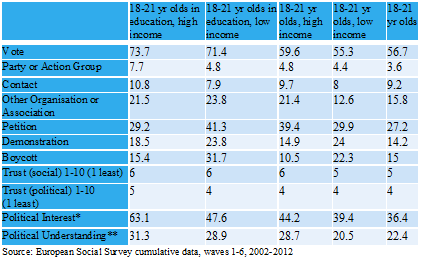

Table 3: Political participation of 18-21 year olds in the EU based on being in education and household income

Table 3 shows that being in education boosts participation for 18-21s in almost all political acts, especially for those from low income backgrounds, who actually outperform those from high income backgrounds in education for working for an organisation or association, signing a petition, going on a demonstration, or participating in a boycott. It also shows that 18-21 year olds in education from low income backgrounds outperform those from high income backgrounds who are not in education on these measures, as well as being significantly more likely to vote.

The ESS data shows that the most active in most forms of civic and political participation are those with a high education (see Table 1). Interestingly, it would seem that being in education neutralises the differences between high-income and low-income groups with regards to levels of civic and political participation. The key question is why? In our view, this is likely to be due to the political socialisation effect of educational establishments, which provide students with social networks and a culture of participation, underpinned by a relatively democratic ethos. It is not possible to test this claim with the ESS data, but it is consistent with the findings of the Citizenship Education Longitudinal Study, which has been surveying the civic learning, behaviour, and attitudes of young people in England since 2001.

We draw two main conclusions from our analysis of the ESS data. First, educational institutions play a vital role in scaffolding the transition of young people into adulthood, for example, by providing them with opportunities to engage in forms of civic and political activity. And second, educational establishments play a key role as social levellers, as they are particularly effective in providing a platform for civic and political engagement for young people from deprived backgrounds. In our view, this places added emphasis on the role of educational organisations in nurturing such engagement.

—

Note: this post originally appeared on the Crick Centre for Understanding Politics blog. For academic references see the original version. It represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Dr James Sloam is a Reader in Politics and co-coordinator of the Youth Politics Unit at Royal Holloway, University of London. He has published widely on the subjects of youth politics and youth protest in Europe and the United States. Shorter pieces on youth participation can be found on the Fabian Society and LSE Europe websites and in the Political Studies Association’s (PSA’s) Political Insight magazine.

Dr James Sloam is a Reader in Politics and co-coordinator of the Youth Politics Unit at Royal Holloway, University of London. He has published widely on the subjects of youth politics and youth protest in Europe and the United States. Shorter pieces on youth participation can be found on the Fabian Society and LSE Europe websites and in the Political Studies Association’s (PSA’s) Political Insight magazine.

Dr Ben Kisby is a Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Lincoln. He has published a number of articles, book chapters and a monograph on citizenship education. He co-convenes the PSA’s Young People’s Politics specialist research group with James Sloam, Jacqui Briggs and Emily Rainsford, and drafted the PSA’s Charter for Active Citizenship in Higher and Further Education with Andrew Mycock and James Sloam.

Dr Ben Kisby is a Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Lincoln. He has published a number of articles, book chapters and a monograph on citizenship education. He co-convenes the PSA’s Young People’s Politics specialist research group with James Sloam, Jacqui Briggs and Emily Rainsford, and drafted the PSA’s Charter for Active Citizenship in Higher and Further Education with Andrew Mycock and James Sloam.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Educators in the #UK are also considering the importance of #CivicEd and engaged youth https://t.co/6HfvMkDPik

Education can boost active citizenship, say Drs @james_sloam and Ben Kisby on @democraticaudit: https://t.co/GaI26uFZwV

#Education can provide both the opportunities and capabilities to make active #citizens of our young people https://t.co/6GykNss27s

RT @democraticaudit: Can education can provide the opportunities and capabilities to make active citizens of our young people? https://t.co/…

Interesting article https://t.co/udEGYJiDU9 #citizenship

Educational institutions are a vital factor in influencing young people’s levels of political disengagement

https://t.co/TBCDTMLfDl

Being in education boosts young people’s political participation neutralising gaps between high and low income groups https://t.co/j877xeK300

Education can provide both the opportunities and capabilities to make active citizens of our young people https://t.co/FXFT2ryX2K

Education can provide both the opportunities and capabilities to make active citizens of our young people https://t.co/Ck4N4Kedpk #Option2…