The Finns Party and UKIP have shared a similar journey from the outside to the mainstream

UKIP finished second in hundreds of seats in the UK’s General Election, though only managed to claim one MP. The Finns Party, a UKIP-like populist party in Finland, are set to enter government. Mari Niemi, a keen observer of UK and Finnish politics, charts the assent of these two outsider parties seeking to simultaneously join and shake up the establishment.

In both Finland’s and the United Kingdom’s (UK) general elections this spring, the success of the two populist and EU-sceptic parties has gained international interest. How have the two populist parties, the Finns Party and the UK Independence Party (UKIP), conquered voters’ coffee-table discussions and even their hearts?

In order to grow, a newcomer party faces two challenges: first, to gain visibility and second, to earn credibility. In achieving both, media publicity is an essential tool. The media’s insatiable appetite for the populist party leaders’ public persona and the parties’ provocative, well-tailored messages has helped achieve the first task. Undoubtedly, the voters’ recognition of these parties has grown.

Gaining credibility has been more challenging, partly because the focus of media scrutiny has extended to those party members and candidates whose views or actions have been less advantageous for these parties’ plausibility.

The political, societal and cultural contexts in which UKIP and the Finns Party have emerged and operated are predominantly different. However, in the media, the rise of both parties has followed similar paths. It is no surprise that these populist, nationalist, EU-sceptic, leader-centred and anti-elite parties that are willing to limit immigration share many common features. Furthermore, the long-term friendship and cooperation between the party leaders, Timo Soini and Nigel Farage, may explain some of the resemblances in the parties’ strategies and even in their rhetoric.

Both Farage and Soini have been personally extremely successful in drawing media attention to themselves. Their jovial public personas, gift for delivering one-liners and capacity for representing themselves as the everyman standing up for ‘the people’ against the elites have been crucial, especially in cultivating approval in tabloids. In terms of speaking to these parties’ potential voters, this connection has been vital.

Other important factors that explain the success of the UKIP and the Finns Party in hoovering up exposure include use of carefully selected celebrity candidates, distinctive policy topics, damage control in response to accusations of racism and male chauvinism and finally, the attention created by the growing support for these parties.

In terms of candidate selection, the parties made their breakthrough in broader public awareness in the past consecutive years. At an early stage, both managed to recruit well-known, controversial celebrity candidates who were able to command media attention.

In Finland, this role was played by Tony Halme, a professional wrestler famous for his appearances in the World Wrestling Federation under the alias Ludvig Borga. In the 2003 general election, he was among the top-five vote-pullers in the country with over 16,000 personal votes, gained largely from Helsinki’s housing estates. Halme’s vote tally helped Soini to enter the parliament under the proportional representation.

In the UKIP’s case, a similar task fell to Robert Kilroy-Silk, a former Labour MP and academic, who had become a national celebrity after hosting his own chat show on television. As described by Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin in Revolt on the Right (2014), around his candidacy in the 2004 EU elections, Kilroy-Silk began to dominate the UKIP’s media coverage and helped broaden its appeal.

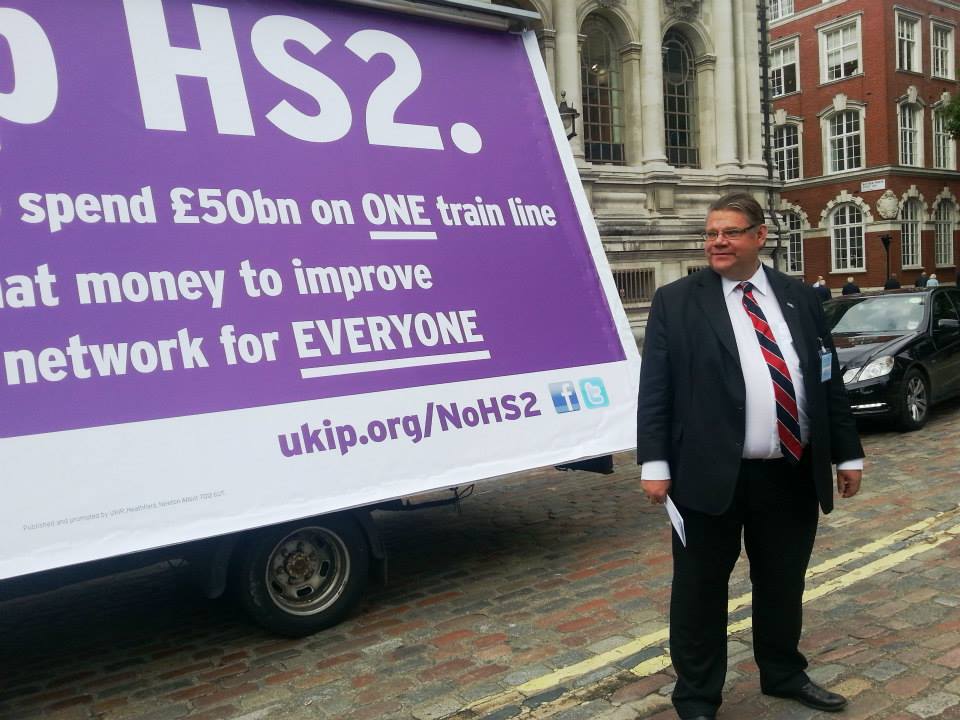

Regarding policy topics, resilient EU criticism and willingness to challenge the predominant immigration policies by stressing their negative by-products have played a central role in the visibility of both the UKIP and the Finns Party. Since both have offered alternative views and rhetoric compared to the mainstream parties, journalists have also had something worth reporting on – a break from the political norm.

These parties’ well-known anti-immigration stance has also attracted supporters and candidates whose own opinions do not bear public scrutiny well. As a result, both the UKIP and the Finns Party have been repeatedly accused of holding xenophobic and discriminatory views against minorities and immigrants. Typically, the accusations have concerned party members’ or candidates’ statements on social media platforms, spaces less amenable to party editing and scrutiny.

Although this kind of publicity can be – and often is – damaging, it also gives the involved political parties an opportunity to respond publicly. Defending their parties against the criticism provides their leaders and spokespersons a chance to explain and market their parties’ agendas. While many voters find anti-immigrant statements deplorable, others are pleased to hear them rehearsed and welcome such views.

The UKIP and the Finns Party have been characteristically men’s parties, as men have been and remain over-represented among their candidates, representatives and voters. These parties have offered a political alternative to the voters who feel equality has ‘gone too far’. The views not only on immigrants but also on gay rights, feminism and women’s role in working life and politics expressed from these parties’ ranks have created headlines – and provided the parties free space in the media to promote their world-views and values.

Interestingly, too, these parties’ rising support has become a topic in its own right and created further headlines. Additionally, their growing success in the opinion polls has ensured both Farage and Soini places in their respective televised leaders’ debates.

Prior to the 2011 general election, there was extensive public discussion on whether the Finns Party should also be invited to a leaders’ debate that traditionally included only the leaders of the three largest parties. Since Soini’s party was the smallest in the parliament at that time, the TV broadcasters’ decision to invite him instead of leaders from mid-sized partiers was met with criticism. The rationale for his inclusion was principally the party’s rapid rise in the opinion polls.

A debate similar in tone and content followed in the UK before the 2015 election, as broadcasters offered a plan to invite Farage to the live debates, alongside David Cameron, Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg. The criticised plan was later revised to include all leaders of the seven main political parties.

Both Farage’s and Soini’s media relations have two main qualities: they feel at home with journalists and are skilled in using the given airtime to their advantage. However, in a typical populist party manner, both men are equally ready to accuse the ‘media elite’ of being biased against their parties.

After the general election in April, a new phase is beginning in Finnish politics, as the Finns Party is entering the government. The party has become the second largest one and is in the middle of negotiations on the coalition government’s platform. Proportional representation and the normality of coalition governments have made it easier for the Finns Party to make a breakthrough in national politics compared to its UK equivalent.

Due to the UK’s first-past-the-post system, which is challenging for a fringe party, the UKIP gained only one seat in the general election held this May. Although the party’s share of votes increased by 9.5 per cent from the 2010 election, Farage was unable to win a parliament seat and resigned. However, a few days later he revised his decision and decided to continue as the leader of UKIP.

After 18 years of leadership, Soini’s position remains solid. His next challenge is to convince his voters that it is necessary for every party to make compromises in a coalition government. In this case, his media skills are needed once again.

—

It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Dr. Mari K. Niemi is a Senior Researcher at the University of Turku and a Visiting researcher, University of Strathclyde

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here: democraticaudit.com/?p=13148 […]

this is going to be an interesting contest between the two.

Just to keep in touch with the British policy

The Finns Party and UKIP have shared a similar journey from the outside to the political mainstream https://t.co/Bf82TNFlpL

@MariKNiemi Good piece. https://t.co/ERBcsK4PtK

The Finns Party and UKIP have shared a similar journey from the outside to the mainstream https://t.co/DcLyYc2eit

Good piece on the similarities of the #FinnsParty and #UKIP. https://t.co/2wc6BMwfkv

The Finns Party and UKIP have shared a similar journey from the outside to the … – Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/EVr4StSiN9

The Finns Party and UKIP have shared a similar journey from the outside to the mainstream https://t.co/bMbRjVUzRA #Option2Spoil

The Finns Party and UKIP have shared a similar journey from the outside to the mainstream https://t.co/z09j75Q81d