A written British constitution would do much to enhance Britain’s democracy and the wellbeing of its citizens

Britain famously has no written constitution, opting instead to govern itself with reference to a set of conventions, laws, and traditions without formal codification. Vittorio Trevitt argues that this system has past its sell-by date, and should be replaced by a written constitution.

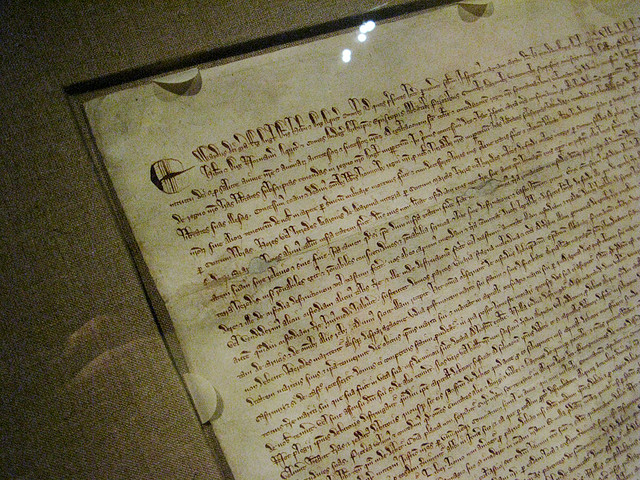

Credit: Paul Sieka, CC BY NC SA 2.0

The United Kingdom has a long tradition of constitutional reform, as demonstrated by the likes of Magna Carta (which afforded rights to certain citizens, and set the standard for common law) and the Bill of Rights of 1686 (which strengthened parliamentary powers and the rights of the monarch’s subjects). Nevertheless, Britain has the arguably unenviable distinction amongst democratic societies of being one of the few without a written constitution; a single, easily accessible document through which all members of society are able to determine what rights and freedoms they are entitled to by law. It is regrettable that our democratic system is marked by the absence of such an important document, as the British people have much to gain from the establishment of a written British constitution.

Various observers have questioned the need for Britain to have a written constitution, with one line of argument holding that such a charter would undermine parliamentary sovereignty by placing parliamentary decision-making at the mercy of unelected judges policing the constitution, and another that Britain’s “unwritten constitution” has served this country well up until now, thereby negating the necessity of challenging the status quo. Despite these arguments, there are numerous benefits that a written constitution could bring to British society. It would be advantageous to ordinary Britons by serving as a comprehensive source from which they can learn how the State is meant to function on their behalf and provide their rights with a degree of security, including such essential elements of liberal democratic societies as the right to a fair trial, freedom of speech, and protection against discrimination in all shapes and forms.

A written constitution could also have the positive effect of enhancing democratic institutions and encourage participation in the political process. It could do this by bolstering the independence of local government through the provision of a constitutionally defined sphere of fiscal and policy autonomy, in turn increasing the influence of ordinary people on issues affecting their everyday lives. In drafting a written constitution, citizens can also be given a consultative role in shaping the key principles of a charter affecting virtually all aspects of their lives, making people currently apathetic about politics feel that they have a degree of control over the future direction of the United Kingdom, and increase their faith in the political system.

In order for a written British Constitution to be legitimate in the eyes of the nation as a whole, however, it would need to do more than protect civil liberties, promote democratic participation, and provide safeguards against discrimination. It would need to have a strong social element, guaranteeing a broad range of rights aimed at ensuring that all British citizens have an adequate quality of life. For those at work, these could include minimum rights such as maximum working hours, trade union representation, and an adequate minimum wage. For families and dependents, such rights could encompass universal entitlement to social security and health care, together with access to all forms of education, placing statutory duties on governments to ensure that no one is denied a decent education because of individual costs, and that everyone receives the necessary medical treatment and welfare support. Although most of these entitlements already exist in practice, and have been enshrined in law over the years in countless Acts of Parliament, constitutional guarantees of such basic rights could shield them from emasculation or even abolition on the part of governments of any ideological persuasion. In this sense, a written constitution would serve as a sanctified charter through which members of the public can uphold their rights as British citizens; rights that the State not only has a moral obligation to protect, but to put into practice as well.

Across the world, constitutions have acted as bulwarks against attempts to reduce social protections and public services, while also upholding worker’s rights, showing the kind of safeguards a written constitution could provide for the British people. In the United States, the signature health care reform of the Obama Administration was upheld by the Supreme Court on constitutional grounds back in 2012, while more recently a judge in New Jersey ruled that a cut made to the state’s payment to New Jersey’s public sector pension system by governor Chris Christie was unconstitutional, and had “substantially impaired” the contractual rights of workers in that state.

In Greece, a planned privatisation of the country’s largest water utility a year ago was blocked by a top Greek court on constitutional grounds, arguing that the proposed sale could have negative consequences for public health. In Canada, a recent ruling by the Supreme Court declared the right of workers to strike to be “fundamental and protected by the Constitution” after striking down a provincial law that prevented public sector workers from going on strike. This was a decision seen by various analysts as constituting a revolution in Canadian labour law, and one that was applauded by labour groups.

Across the European Union, constitutional courts in various member states have mitigated the social impact of various austerity programmes in recent years. In Portugal, the Constitutional Court has blocked a number of proposed cuts to wages and pensions, while in Lithuania and Latvia, the constitutional courts of those countries revoked previous reductions in pension payments. Here in the United Kingdom, the concept of a written constitution as a defender of social and economic freedoms was evoked by numerous political figures during last year’s Scottish independence referendum, with Alex Salmond backing the inclusion of a free NHS in a Scottish constitution as a means of shielding the service from policies of austerity and privatisation.

Having strong social guarantees in a written constitution does not mean, however, that provisions such as a living wage and access to all levels of education are guaranteed for all citizens; the political will to put such bold ideals into practice must also be present. Although South Africa, for example, has one of the world’s most progressive constitutions, with rights to water, housing, and sufficient food, the country is far from ensuring that these are enjoyed by all of its people. However, by having clearly defined social and economic rights that all Britons are entitled to from birth, this sets high standards for governments to meet in working towards the goal of building a more just and prosperous society for all. The requirements of the 2010 Child Poverty Act, for instance, could be extended by making it a constitutional obligation for governments of all political stripes to eliminate the scourge of childhood poverty, providing anti-poverty campaigners with a strong legal basis to hold governments to account in meeting this ambitious goal.

There is, therefore, a solid case for the introduction of a written constitution for the United Kingdom. Not only would its realisation bring material and civil benefits to ordinary people, but it would also do much to enrich British democracy. By closing this democratic deficit, the establishment of a written British constitution would not only bring the United Kingdom more in line with other democratic nations, but by laying down a series of social and economic obligations for governments to adhere to, could very well shape the direction of British social policy for decades to come.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Vittorio Trevitt is a freelance researcher and writer from Brighton with a research interest in local and national politics.

Vittorio Trevitt is a freelance researcher and writer from Brighton with a research interest in local and national politics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Does the UK need a written constitution? https://t.co/2SndDQNGdH (via @democraticaudit)

RT @PJDunleavy: A written British constitution would do much to enhance Britain’s democracy and the wellbeing of its citizens https://t.co/i…

Do we need a written constitution for the UK? https://t.co/WerV3jXO1K

A written British constitution would do much to enhance Britain’s democracy and the wellbeing of its citizens https://t.co/fj71Dhv4T5

#CompGov #BringCivicsBack MT @democraticaudit: A written British constitution will enhance democracy and citizenry https://t.co/bdxX9Kvzjf

A written British constitution would do much to enhance Britain’s democracy and the wellbeing… https://t.co/sViMOmShlS https://t.co/thzRikoxhP

A written British constitution would do much to enhance Britain’s democracy and the wellbeing of its citizens https://t.co/8T1pogbO43