The importance of regime similarity to explain democratic diffusion

Studies of democratic diffusion have generally emphasised the role of geography in explaining waves of democratisation. Edward Goldring and Sheena Chestnut Greitens show that regime type has been significantly under-appreciated. Dictatorships often break down and even democratise along networks of similar regimes rather than via geographical proximity. Their work has important implications for questions of authoritarian survival and durability, as well as understanding the diffusion of political phenomena across the world, including in the UK.

Democracy protestors, Hong Kong, 2018. Picture Etan Liam/(CC BY-ND 2.0) licence

Continued waves of protest and democratisation in world politics have prompted renewed interest in how international factors shape global patterns of democracy and dictatorship. Studies of democratic diffusion – broadly conceptualised as the transmission of democratisation across international borders – often emphasise geographic proximity: democratisation in a country or region makes democratisation in neighbouring territories more likely. However, motivated by qualitative analysis of China in 1989, we explore a new research question: do autocratic breakdown and democratisation diffuse across geographically proximate countries, or along networks of countries that share similarities in regime type?

How networks of similar regimes shape diffusion

In 1989, China risked regime collapse via diffusion from two distinct international sources: geographically proximate countries, and other single-party communist regimes. Many previous theories of democratic diffusion suggest that, to the extent the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) perceived a threat from protest spilling across borders, it should have perceived the threat as coming from nearby regimes in Asia. Indeed, there was ample evidence on which to base this fear. Popular mobilisation had brought democracy to the Philippines (1986), South Korea (1987), and Taiwan (1987), and prompted autocratic regime replacement in Myanmar/Burma (1988).

However, our analysis of Chinese-language sources reveals that the CCP was threatened not by geographically proximate authoritarian breakdowns, but by breakdowns in other single-party communist regimes, especially in Eastern Europe. The CCP’s concern was that Chinese protesters would emulate Polish and Hungarian examples and thereby spread anti-regime protests from Europe to China. Premier Li Peng told President Bush in February 1989, for example, that China sought to avoid ‘the kind of labour problems that Poland is experiencing’. He drew direct parallels between protesters’ actions in Poland and China, from the names of protest organisations to their demands for protest movement legalisation. Simply put, in 1989, China’s leaders believed and acted as if regime similarity, not geography, drove the risk of autocratic breakdown and democratisation diffusing into China – something very different from what existing theories would suggest. We wondered: what if China’s leaders were assessing patterns of diffusion correctly, and regime similarity mattered more for diffusion than geographic proximity?

Theoretically, there is reason to believe that regime type should play an important role in the diffusion of autocratic breakdown and democratisation. Recent research shows that anti-regime protesters use cognitive shortcuts to copy tactics from elsewhere, without careful consideration of how these tactics will work in a different political environment. The regimes that that protestors confront, however, may not be very much alike: different regime types (military, single-party, personalist, etc.) have interests, structures and tools that can either make them vulnerable or facilitate survival against popular mobilisation. For that reason, a country’s specific type of authoritarianism should shape how vulnerable it is in the face of popular protest. Thus when protest erupts, regime type is likely to differentiate the autocracies that survive from those that break down.

Regime similarity should also predict diffusion of democratisation (not just autocratic breakdown), for two reasons. First, protest movements that are sophisticated enough to analogise appropriately to engineer autocratic breakdown are more likely to also learn the right lessons to bring about democratisation. Second, regimes that share specific vulnerabilities to popular mobilisation may share other features that are conducive to both breakdown and democratisation, such as a military that supports democratisation, or is at least willing to negotiate and compromise with protest leaders.

Overall, diffusion based on networks of regime similarity should help explain when authoritarian regimes break down, and when they democratise.

Testing diffusion from similar regimes

We test this argument quantitatively, using data on 199 autocratic regimes from 1961 to 2010. We use spatial econometric tools because these allow us to identify and compare the influence of spatial and non-spatial neighbours. In other words, we can distinguish between the effects of diffusion driven by events in geographic neighbours, and effects driven by events in similar regimes, irrespective of geographic location.

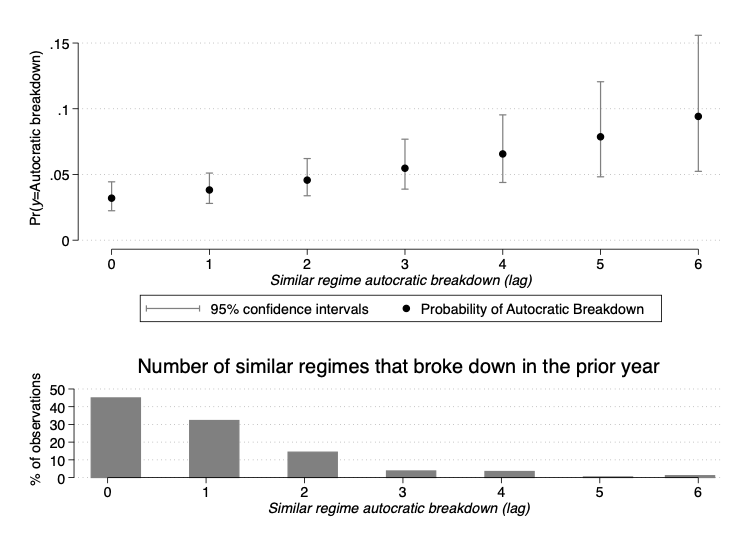

Our analysis reveals two principal findings. First, the role of geography in driving democratic diffusion has likely been overstated; including regime similarity washes out much of the effect of geography. Second, when both factors are accounted for, the effect of diffusion driven by networks of similar regimes is much bigger than the effect of geographic proximity. The figure below shows that the probability of a country experiencing autocratic breakdown notably increases as the number of similar autocratic regimes experiencing breakdown in the previous year increases. The pattern is the same when we look at democratisation as an outcome.

Figure: likelihood of autocratic breakdown

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying article in Comparative Political Studies.

We also examine whether authoritarian regimes are more strongly influenced by breakdowns or democratisations in similar regimes when those regimes are also more geographically proximate. If protests that trigger breakdown or democratisation diffuse primarily to geographically proximate countries, then geography or region will act as either an enhancing or a limiting factor on regime-based diffusion processes. We find some evidence to support this argument, but it is more limited than the evidence showing the importance of regime type alone.

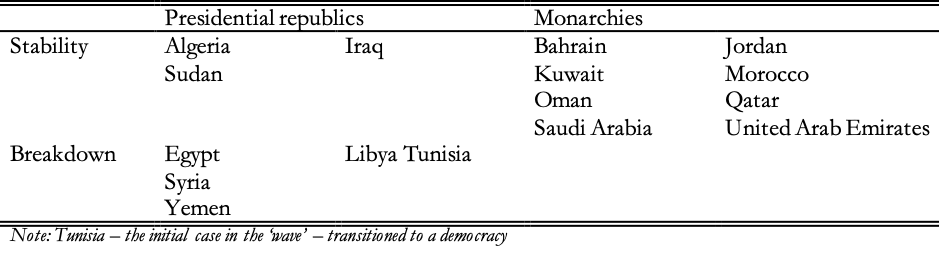

We find further corroboration in two out-of-sample qualitative examples: the 1848 revolutions in Europe and the Arab Spring. During the Arab Spring, nearly every country in the Middle East and North Africa experienced popular mobilisation, but transition outcomes differed dramatically: incumbent replacement occurred in just four countries, and only Tunisia democratised. The table shows that regime subtype correctly predicted a high percentage of these outcomes: monarchies survived, while presidential Arab Republics were more likely to breakdown.

Table: Arab Spring outcomes by regime type

Conclusions

New knowledge about the diffusion of autocratic breakdown and democratisation will improve our understanding of authoritarian survival and durability. One of the primary threats that dictators must counter – as highlighted by the Arab Spring – comes from popular movements. Our results illuminate which dictatorships are likely to succumb to popular movements, and which have structural or institutional characteristics, generally developed over the long-term, that help them survive in the face of mass mobilisation and crisis. From the perspective of practitioners, our findings also suggest that pro-democracy civil society groups will maximise their chances of success if they identify what type of movement tactics have been most successful against other regimes of a similar type.

These findings also pose important questions about the diffusion of other political phenomena. Our theoretical logic focuses on differences in autocratic regimes’ institutions. But protesters’ abilities to transplant tactics from one context to another may depend on alternative networks like linguistic or religious connections. Recent years have also witnessed the diffusion of alternative political phenomena, including successful populist movements, but systematic analysis of when and how populism takes hold is still developing. Our research highlights the value of understanding how interactions between institutional, societal and transnational factors shape the processes by which political phenomena spread globally, whether these processes have to do with democratisation, populist governance, or democratic backsliding.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit. For a longer discussion of this topic, see the authors’ recent article in Comparative Political Studies.

About the authors

Edward Goldring is a PhD Candidate in Political Science at the University of Missouri, a Korea Foundation Fellow, and a US-Asia Grand Strategy Fellow at the University of Southern California.

Sheena Chestnut Greitens is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Missouri, a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution, an Adjunct Fellow with the Korea Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and an Associate in Research at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.