Have changes in counterterrorism legislation before and after 9/11 curtailed civil rights?

Nicole Bolleyer examines the extent and form of legal changes across five western countries in the decades that span 9/11 and finds that in general the level of legal constraints on civil liberties has grown, though with considerable variation between countries and in types of restrictions.

Picture: Elliot Brown/(CC BY 2.0) licence

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, concerns became wide-spread that established democracies might develop ‘illiberal’ tendencies. One indication of such tendencies is the expansion of legislation restricting (otherwise legitimate and constitutionally protected) activities of civil society actors such as charities to prevent the exploitation of democratic rights by internal actors hostile to democracy. While studies of changes to counterterrorism legislation have substantiated such concerns, over-time comparisons of the frequency and nature of legal change across countries and across a broader range of potentially affected policy areas have remained relatively rare.

Have legal changes – especially those after 9/11 – led to an overall increase of restrictions on civil liberties? If so, do we find similar trends across democracies and are there policy areas that were particularly concerned by such developments?

To be able to address these questions, the ‘Regulation Civil Society Project’ assessed changes in statutory counterterrorism legislation (broadly defined) from 1980 to 2013 in the five long-lived common law democracies Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand and the UK. Building on Knill et al’s methodology for the cross-national measurement of policy expansion and policy dismantling , original legislation was coded across seven different policy areas, each area sub-divided in several policy items in which the presence and direction of legal change was assessed. The resulting ‘Defensive Democracy Dataset’ covers the following policy areas: ‘proscription of groups’, ‘derivative offences criminalising involvement with/support of proscribed groups’, ‘regulation of demonstrations’, ‘sedition offences’, ‘restrictions on racist propaganda and hate speech’, ‘surveillance, infiltration and information gathering’ and the ‘coercive power of police and security forces related to counterterrorism’. The resulting dataset captures, on an annual basis, the density (i.e. the number) of legal changes in each of these areas as well as their direction, i.e. whether the changes restricted the rights of those actors targeted by the legislation – thereby broadening the leeway for states to constrain civil society – or whether changes reduced such restrictions, thereby making legal environments more permissive.

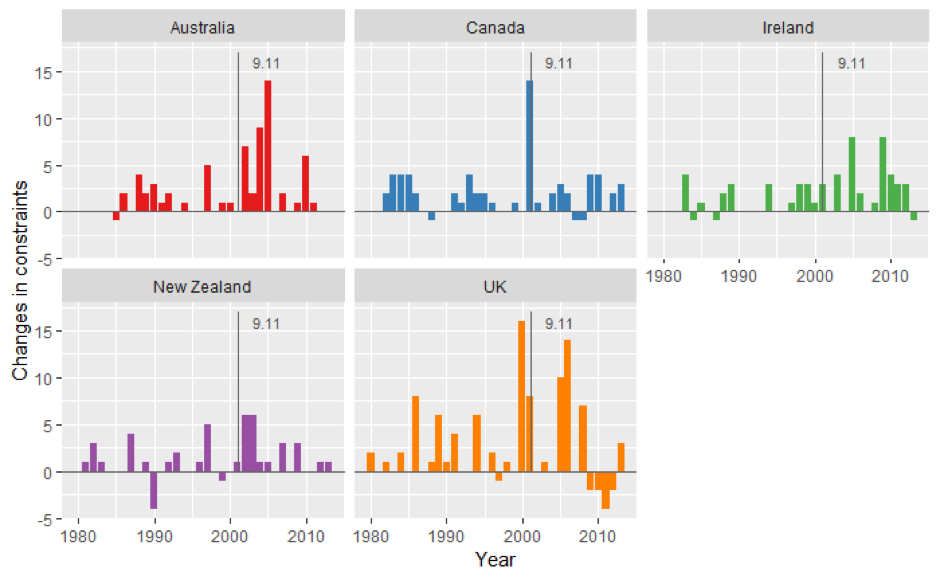

Between 1980 and 2013, we have identified across the five countries covered a total of 431 legislative changes introducing constraints and 134 changes making legislation more permissive. Hence, while the introduction of constraints dominates the overall picture, the development of legislation has not been uniform. Figure 1 shows changes in legal constraints (with negative values indicating a dominance of permissive changes) country by country, before and after the 9/11 attacks. Overall, legislative reforms tended to increase the intensity of constraints, though there are periods during which lawmakers have relaxed legislation. This was for instance the case in the UK from the late 2000s, after constraints had intensified considerably in the aftermath of the 2005 London attacks. These had led to the passing of harsher legislation across all areas including proscription of groups, derivative offences, surveillance and infiltration and the powers of police and security forces, a range of which were relaxed subsequently (for differences across policy fields see Figure 2).

As expected, the 9/11 attacks have been an important turning point: considering all constraints adopted across the five countries, we have 2.55 per year on average in the post 9/11 period and 1.25 in the period between 1980 and 2000. However, even though the five democracies share this broader trend towards increasing legal constraints, the level of constraints introduced and the shift that occurred in the post 9/11 period are still quite different. The UK – whose national security laws have been characterised as particularly draconian compared to other European democracies – has overall adopted the most rights-restrictive approach among the long-lived common law democracies. Over the whole period and across the policy areas studied, it implemented – followed by Australia – most legal changes which, in turn, contained the highest share of legal constraints. Interestingly, comparing the periods before and after 9/11, the difference in average constraints (in relation to permissive changes) is least pronounced in the UK (considering only the number of new legal constraints, more were introduced before 9/11). In contrast, the relative increase of constraints has been most pronounced in Australia.

Figure 1: Legal constraints in the long-lived common law democracies (1980–2013)

Source: ‘Defensive Democracy Dataset’.

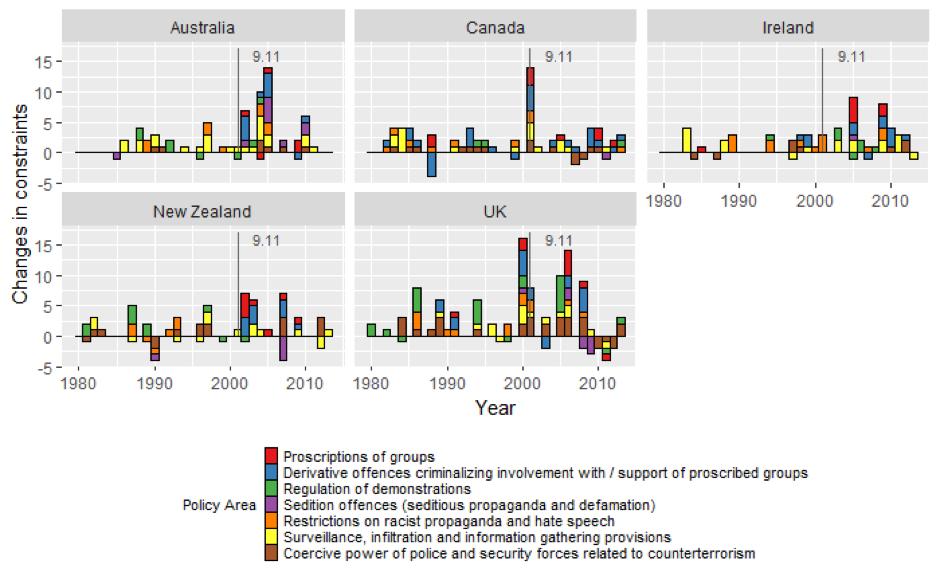

Considering differences between policy fields as displayed in Figure 2, tendencies towards the adoption of stricter legislation in the post 9/11 period (in comparison to the period prior) are particularly pronounced in the policy areas ‘proscription of groups’, ‘derivative offences criminalising involvement with/support of proscribed groups’ and ‘coercive power of police and security forces related to counterterrorism’. In contrast, in the areas ‘sedition offences’, regulation of demonstrations’ as well as ‘surveillance, infiltration and information gathering’ the relative trend towards constraints was weaker post 9/11 than before. That said, comparing patterns of change over the whole period from 1980 onwards, ‘surveillance, infiltration and information gathering’ is the policy area in which the highest number of legal constraints have been adopted (as compared to other areas), i.e. a notable shift towards constraints occurred before 9/11 already. In contrast, in the area of ‘sedition offences’ we find an equal number of changes that enhanced and reduced constraints over the whole period. More specifically, we find a ‘liberalisation’ of legislation in this area indicated by a higher number of changes that made legislation more permissive as compared to introducing new constraints in Canada, New Zealand and the UK.

Figure 2: Legal constraints in the long-lived common law democracies by policy area

Source: ‘Defensive Democracy Dataset’.

While the analysis of the ‘Defensive Democracy Dataset’ is on-going, an initial qualitative assessment can be found here: Bolleyer N. and Gauja, A. (2017). Combating Terrorism by Constraining Charities? Charity and counter-terrorism legislation before and after 9/11. Public Administration.

For more information on the ‘Regulating Civil Society Project’ see: https://socialsciences.exeter.ac.uk/regulatingcivilsociety/

Funding: This research was generously supported by a British Academy/Leverhulme Small Research Grant (132160) and by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–13)/ERC grant agreement 335890 STATORG). This support is gratefully acknowledged.

This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Democratic Audit.

About the author

Nicole Bolleyer is Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Exeter.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.