Full of sound and fury: Is Westminster’s e-petitioning system good for democracy?

Online petitions to Parliament have become a ubiquitous part of political campaigning. However, writes Carys Girvin, as the UK system is currently designed, without mechanisms for real public deliberation, they can be crude tools that fail to enhance participatory forms of democratic decision-making. Examples from Germany and Finland suggest possible improvements.

Picture: Petition.parliament.uk page, via an Open Government Licence 3.0

On our Facebook timelines, in our email inboxes, and embedded in the articles we read online, e-petitions appear. E-petitions are a call to our government for change, they highlight policy issues and expose miscarriages of justice. ‘Put pressure on Libya to take action to stop enslavement of black Africans’, ‘Stop the privatisation of the NHS’, ‘We want a public enquiry into the James Bulger murder case’, are the first petitions that came up when I took a quick look on the government’s e-petition website. The causes often pull at our heart-strings or ignite our indignation, so it is easy to jump on board and pledge our support. Just think: with a few clicks of a button we have contributed to an effort to bring about a positive change. It is so quick, and gratifying, we barely have time to consider what the e-petition system is really doing and the impact it’s having on our democracy.

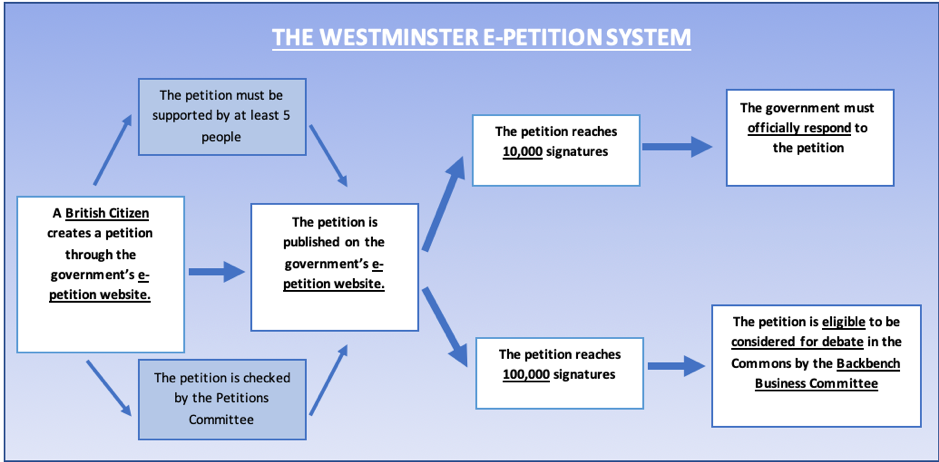

E-petitions have played a role in Britain’s political system for over 10 years. In 2002, Robin Cook, leader of the House of Commons under Blair, stated that the ‘internet offers us a tool for participation without precedent in democratic history’ and it was in this spirit that that government brought in the first e-petitioning system in 2006. A new system was introduced by the coalition, which registered 22,000 individual petitions in its first five months, compared to an average of 316 petitions per session under the previous system. Its popularity is unsurprising: it has become one of the most accessible channels by which citizens can communicate with government. The diagram below gives an overview of how the system works.

Source: petition.parliament.uk

The process appears logical and straightforward. There is some oversight to prevent inappropriate or irrelevant petitions, but it is generally inclusive of people’s demands and concerns. The government is bound to respond to accepted petitions, so long as they meet the required number of signatures. In theory an efficient channel of communication between petitioners and the government is created. However, despite the appearance of a well-functioning system, these e-petitions rarely result in bringing about much tangible change. Which leads us to ask, is the e-petition system just a democratic façade?

A key reason that e-petitions struggle to bring about change is that the system exists within the confines of a representative government. It is the political elites within Westminster who create the space for participation to occur, and this space is often created ‘precisely and narrowly’. Built in to the ‘participatory space’ are numerous opportunities for the government to ignore or dismiss submitted proposals if they are problematic or deemed irrelevant. Firstly, before it is published the Petitions Committee have the ability to reject a petition on the grounds of being repetitious, offensive, extreme, containing confidential material or libellous. Secondly, whilst the government is required to respond at 10,000 signatures, there are no requirements as to how the government should respond. Many e-petitions will receive a formal reply simply explaining that the government will not take action on the issue in question. Similarly, when 100,000 people sign an e-petition there is an opportunity for the issue to be debated in the House of Commons, but there is by no means a binding guarantee and for the most part petitions are not debated.

Even if the process of e-petitioning was not so hampered by elite control, it may still continue to be damaging for our democracy. Petitions are often deemed ‘good’ for democracy as they are a method by which citizens can communicate their wants, values, and needs to government. However, if individuals simply state, rather than deliberate over, their views, these preferences are, according to deliberative democratic theory, likely to be less considered and informed.

Since the UK’s e-petition system requires each ‘issue’ to raise a particular quota of support, the individual creating the petition has an incentive to choose an attention-grabbing subject. As a result, the topics covered tend to be sensationalised and over-simplified. For example, two of the most signed e-petitions are ‘Prevent Donald Trump from making a State Visit to the United Kingdom’, which received 1.8 million signatures, and ‘Stop all immigration and close the UK borders until ISIS is defeated’ receiving just under half a million signatures. Whilst this is in an issue with the process of petitioning generally, it is exaggerated when petitioning is done over the internet, when collecting signatures no longer requires word-of-mouth communication in which people explain why their cause is worthy. People can tap into pockets of the internet where they know individuals will agree with them, removing the need for petition creators to explain their reasons to citizens unaware of the issue. Cass Sunstein argues that individuals are particularly prone to clustering into ‘like-minded and homogenous groups on the internet’ which in turn decreases democratic deliberation.

Given these criticisms, the prognosis for the role of e-petitions in our democracy doesn’t look good. Do these concerns relate to Westminster’s system specifically or can they be applied to e-petitions generally? The German and Finnish governments have also introduced forms of national online petitioning.

Germany’s system, known as the ‘Public Petition system’, is similar to the UK’s, with a required quota of ‘electronically submitted’ signatures to a government-run website. The appropriateness of the petition is assessed by members of government and, if the petition fulfils these criteria, the government is bound to address the subject. As in the UK, the online ‘quota’ creates an incentive to sensationalise an issue and give disproportionate power to ‘homogenous online clusters’. The ability of the government to decide the ‘appropriateness’ petitions, once again, brings into doubt how much power is really being given to citizens. In 2010 43% of all petitions submitted were deemed in some way inappropriate or not pertinent.

The German system does vary, however, in the way the government addresses the petition. Successful petitions are discussed with petitioners in a public session of the committee, introducing a deliberative element to the system which is lost in the online quota-filling stage. This seemingly satisfies petitioners, with 91% of those who participated in these committees finding the discussion informative and 87% considering it pertinent. Certainly, this is a more meaningful discourse between policy-makers and citizens than in the UK. However, the number of people who get to engage in such deliberation is incredibly limited compared to the number of citizens who need to sign the petition for it to reach the public committee stage.

For the Finnish system, known as the FCI (Finnish Citizen’s Initiative), the basic process is the same: there is a quota of signatures required, upon which the government is bound to consider the issue raised. Like the German system, successful petitioners or ‘initiators’ can also become involved in the parliamentary process. Unlike the UK or Germany, the petitions do not have to be registered on a government website, other online platforms can be created to do this, so the earlier stages of the petitioning process are less restricted, and subjects cannot be vetoed by government. However, the FCI asks more of the ‘initiators’. They are required to suggest an outline for new legislation or specify how legislation should be changed. This means citizens do not simply make ‘virtuous declarations’ or file complaints, but rather engage in the legislative process. This reduces the likelihood that e-petitions will encourage the over-sensationalisation of issues. This function shapes the petitioning process into something quite different, creating a channel by which citizens can become a direct part of the legislative process, not merely lobbying it from the outside.

As of 2017, of the 600 proposals created on the Finnish system, 16 have made it to parliament and only one has resulted in new legislation. These numbers are not a reason to despair necessarily; the introduction of e-petitions is not an attempt to introduce direct democracy, but to create a process that works alongside a representative system. What is more, the single piece of legislation passed was the legalisation of same-sex marriage, a significant change to a nation’s social fabric. If a participatory process can produce an outcome as significant every 5 years, it is arguably very worthwhile.

The primary concerns with the Westminster’s e-petitioning system are not about how often the process ‘works’, but rather the way ‘undeliberative’, sensationalist and misleading petitions can be detrimental for democracy. The Westminster model could learn from these other systems and adopt a more independent method of gaining signatures online. The secondary stage of responding to petitions could be improved by involving direct deliberation between parliamentarians and petitioners.

Dealing with how the e-petition system sensationalises and simplifies issues and encourages citizens to form homogenous clusters, however, is far trickier. This appears to result from the preference-aggregating nature of petitions, which is exacerbated by the internet. Perhaps, then, the Westminster system should move away from simple e-petitioning and look towards utilising an e-initiative system similar to Finnish one, taking encouragement from the popularity of online participation and channelling that into something that could really enhance the UK’s democracy.

This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Democratic Audit.

About the author

Carys Girvin is a fourth-year student at the University of Edinburgh.

Carys Girvin is a fourth-year student at the University of Edinburgh.

The author would like to thank Oliver Escobar, whose course ‘Public Participation in Democracy and Governance’ was enlightening and engaging, and whose advice was invaluable.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.