England’s local election’s 2018: what’s at stake in Birmingham?

On 3 May, there are local council elections across England. All 101 council seats are being contested for Birmingham City Council, making this closely fought race one to watch. Jack Bridgewater previews the city’s elections.

Council House, Birmingham. Picture: G-Man/Wikimedia Commons

A city that is divided between two football clubs, Birmingham and Aston Villa, will likely be divided once more by Britain’s two largest parties on 3 May, in a tale of red versus blue. On the face of it, Europe’s largest non-county local authority looks like a safe Labour bet. But Birmingham has thrown up interesting results in recent years.

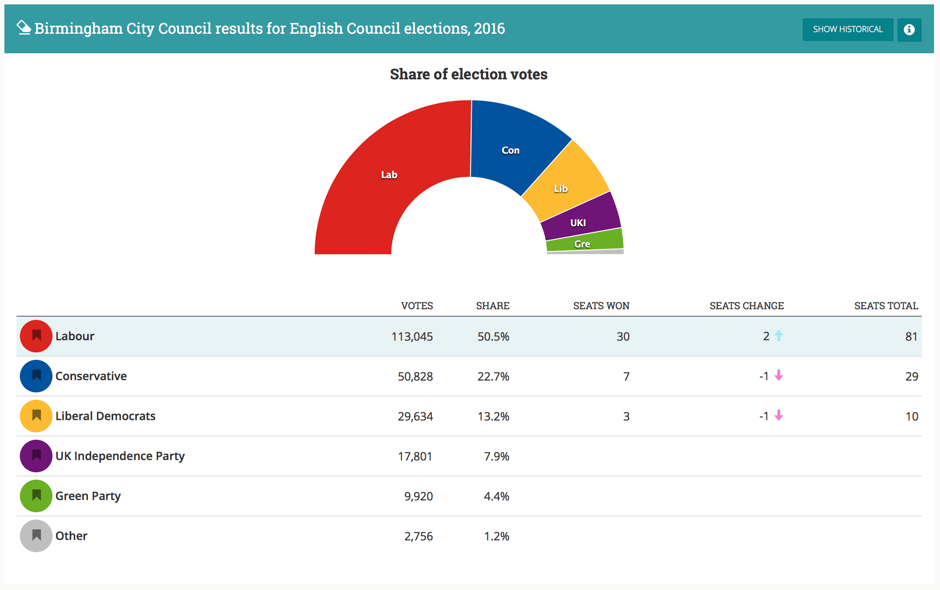

Birmingham City Council has traditionally been dominated by Labour, who ran the council between 1984 and 2004. From 2004, however, no party had a governing majority and a Conservative-Lib Dem coalition ran the council from 2004. The Tories then made steady progress, expanding from their traditional middle-class heartlands of Sutton Coldfield and Edgbaston and into wards that had long been red. At times, the Tories have had the most councillors on the council, but Labour regained control in 2012 and solidified their control in 2016.

In May 2017, however, the West Midlands region – which covers Birmingham, Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Solihull, Walsall and Wolverhampton – elected its first mayor, Conservative Andy Street. Although Birmingham itself voted in favour of Labour’s Sion Simon, the result was closer than you would expect for a city that currently sends only one Tory out of ten MPs to Parliament. Jeremy Corbyn and his party performed poorly elsewhere in the 2017 local elections and with a large Conservative poll lead, the Tories expected to make large gains in the area at the general election. But this was not to be. Theresa May’s misfire of an early general election resulted in no Birmingham constituencies changing hands in June, while all Labour candidates increased their already sizeable majorities.

So, what can we expect in Birmingham on 3 May? There is certainly a lot to play for. Following a boundary review that has increased the number of wards but reduced the number of councillors, all seats are up for contention at once. The two major parties will be heading into the local elections with differing expectations and strategies. Labour will expect to comfortably retain control. The party will be hoping to capitalise on their improved showing in last year’s general election and increase their two-thirds majority on the council. They will be aiming to pick up some wards in more traditional Conservative and Liberal Democrat areas.

However, recent electoral history shows that Britain’s second largest city is not hostile to the Conservative Party in the same way that some of its northern counterparts are. While local elections taking place between general elections tend to punish governing parties, the Tories will take heart from their West Midlands mayoral win. National polls showing a slim Conservative lead will also be cause for optimism. But Birmingham still is not a natural fit for the Conservative Party, and like most large cities in the UK, the demographic make-up of the city will work in Labour’s favour. One of the additional problems the Conservatives will have is that they will likely be outgunned locally if Labour can mobilise their large activist base to pound the pavements for Corbyn’s party.

And what of the other parties? The Liberal Democrats are not traditionally big players in the Midlands, though they drew close to Labour in Birmingham in 2008, holding 32 seats on the council to Labour’s 36. The Lib Dems also ran the council in coalition with the Conservatives from 2004. However, they are ultimately destined for a distant third place. George Galloway’s Respect Party gained several seats a decade ago, which have since reverted back to Labour. UKIP has performed well in recent West Midlands European elections – winning 3 of the 7 regional seats – but the party is unlikely to represent a significant force in Birmingham next month, as their current decline as an electoral force in British politics continues.

While these elections are the first major test of public opinion since last year’s surprising general election, it is worth saying that local elections do not always reflect the national political mood. A recent striking example of this is Labour’s poor showing in the 2017 local elections that was followed by a large increase in the popular vote in the general election, just over a month later. In Birmingham’s case, the city was narrowly split on Brexit, and divided almost down the middle again on whether to have a Labour or Conservative mayor. Labour will expect to make gains, but with all seats up for election the result in Britain’s second city is worth watching.

About the author

Jack Bridgewater is a PhD Candidate in Comparative Politics at the University of Kent. He runs the podcast ‘How to Win Arguments with Numbers’ and his research focuses on voter attitudes towards party leaders. He tweets at @JLBridgewater.

Jack Bridgewater is a PhD Candidate in Comparative Politics at the University of Kent. He runs the podcast ‘How to Win Arguments with Numbers’ and his research focuses on voter attitudes towards party leaders. He tweets at @JLBridgewater.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.