Why mass email campaigns are failing to connect MPs, charities and the people they represent

Mass email campaigns and online petitions have become a ubiquitous part of modern political campaigning. However, writes Jinan Younis, there is an increasing disconnect between those who organise such campaigns and the people whose lives are affected by the issues they raise. Charities and other campaigning organisations need to rethink how they structure digital campaigns.

Campaigning has been taking place in the UK for centuries. Some of the landmark political reforms – the abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, equal marriage – have all come about because of campaigns rooted in a deep public desire to change society for the better. In the digital age, campaigning has moved online.

Over the past decade, charities have moved increasingly towards digital campaigns. We have seen the rise of large-scale petitioning platforms such as Change.org and 38 Degrees. And Parliament responded by creating their own petition website in 2006. Over 39 million digital campaign actions have been taken on 38 Degrees’ platform. On the government’s own platform there were 6.4 million signatures in its first year of operation.

Traditionally, the lead in initiating campaigns has been taken by charities and other larger organisations. But we have also witnessed a rise in volunteer- and individual-led campaigns: some of the most popular and viral digital campaigns are ones that were started by individuals rather than organisations. This shift introduces an interesting new dynamic. The rise of technology has enabled innovation within the charity sector and the creation of a new digital campaigning sector. It has also shifted the idea of who campaigning is for and who can take ownership over campaigns.

These changes affect most crucially people with lived experience. In The Value of the Lived Experience in Social Change, Baljeet Sandhu defines lived experience as: ‘the experience(s) of people on whom a social issue, or a combination of issues, has had a direct personal impact’. Sandhu’s report concluded that ‘experts by experience’ – people who use their personal experience of disadvantage to drive change – need to be ‘meaningfully and equitably involved in social purpose work’. Those with experience of an issue are the very people that should benefit hugely from the rise of digital. Their voices can be amplified through the multitude of channels. Their demands can be seen by those in power. And they can be their own agents of change. But right now, these voices are being overshadowed by the sheer volume of voices that digital campaigning permits.

Esther Foreman’s report Shouting Down the House (2013) found that new methods of online campaigning, such as ‘email your MP’ tactics were drowning out some of the most marginalised people. Foreman wrote: ‘The social media noise levels created by mass digital email campaigns have hidden the legitimate voices who are speaking truth to power’. She recommended the charity sector innovated around digital campaigning to make space for these voices, building on the conclusions of her previous research Peering In (2011) in which she explored the impact of evolving communication models and growing public expectation of the House of Lords. Foreman found that peers did not have adequate tools to manage new online communication tactics from campaigners.

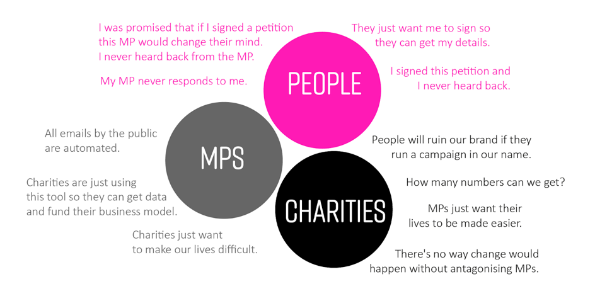

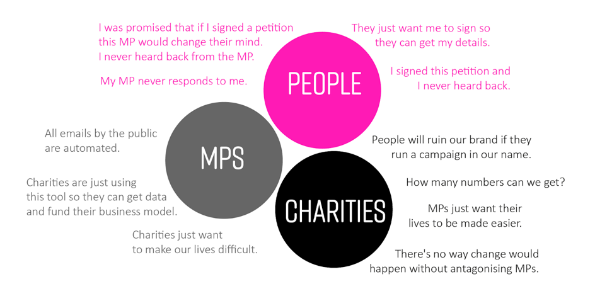

Our research, at the Social Change Agency, highlights the breakdown of trust between the key players in the digital campaigning space: decision-makers, charities, technology providers and those with lived experience. The report suggests that while this is largely a result of the overuse of unfocused email campaigning techniques, it is exacerbated by factors such as metrics of success – which prioritise high numbers over other assessments of impact – the campaign tools used and the availability of resources.

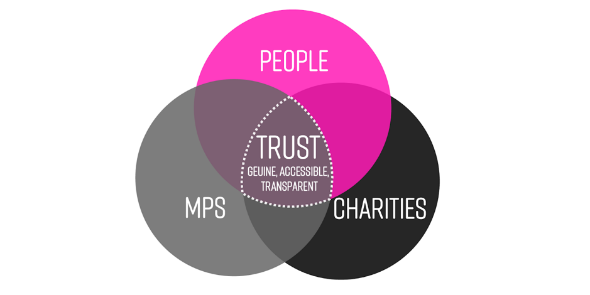

How charities, MPs and the public should be working together

How charities, MPs and the public are currently working together

In our interviews, the overwhelming feeling was that larger charities treated people with real experience of the issues as case studies rather than as active participants in the campaigning process:

‘I hate the term case studies. When we ask for case studies, we’re asking for people to verify what we already think. Whereas if you genuinely want to listen to the lived experience, then that requires communication and direct experience.’

While charities recognise the value of lived experience, Sandhu’s report highlighted the gap between this belief and the way that many charities take action: namely, that they are treated as ‘informants’ rather than ‘change makers’.

Furthermore, there are doubts about the extent to which mass emails and signatures represent real individuals or are grounded in real experience. In our conversations with MPs, it was clear that these voices of constituents with direct experience had the most impact, but that e-campaigns were not seen as the right avenue for this. As Esther Foreman told the 1922 committee in evidence on 2016:

‘Most MPs present believed that charity petitions and emails contained a large part of emails generated by robots. And they’re responding accordingly, with email filter systems and automated responses. Soon, we’ll be in a situation where it’s robots talking to robots’.

The mistrust around digital campaigning extends to the charities themselves. Charities recognise that they are increasingly not trusted by MPs and a growing section of the public – but they too express mistrust of both sectors. One representative from a charity interviewed for the project suggested we take what MPs say with ‘a pinch of salt’. Similarly, many charities interviewed, knowing how uncertain their relationships already are with politicians, admitted the difficulty they face in trusting their beneficiaries to take ownership of their campaigns.

It is those with lived experience who most suffer as a result of this mistrust. They are the individuals to whom the issues most matter. They are the ones whose stories are most likely to influence decision-makers. But rather than being at the forefront of the campaigns, they are relegated to watching from the sidelines. And if they are encouraged and enabled to participate, all too often their campaigning efforts are not met with the success they sought (or had been promised) but with, at best, a proforma response from their local MP. Not only are they left with their issue unresolved, they also are forced to conclude that campaigning is not an effective way for them to speak truth to power.

MPs are still influenced positively by contact with those with lived experience and, in theory, digital campaigning should facilitate this. Charities have an important intermediary role here. However, the rise in digital campaigning techniques has led to a general degradation in the relationship between charities and decision-makers. Too often digital campaigners work in silos; those directly affected by the issue are inadequately supported in participating in campaigning; and charities are poor in identifying which of their campaigning supporters are able to offer their experiences.

The cumulative effect has been to undermine trust in the campaigning process and to cause considerable harm to the relationship between charities and decision-makers. In order to reverse this erosion in trust, we have developed a toolkit for charities to enable the voices of people with actual experience of the issues at stake to be heard better by those in power.

The key recommendations for charities are:

- When innovating on a digital campaigning tactic, ensure that any new initiative is easy, inclusive, connective and far reaching.

- Charities should work towards centring the voices of people with lived experience of the issues at the heart of their digital campaigning.

- Charities should ensure that their work is meaningfully informed by the knowledge and voices of those with lived experience to rebuild trust with decision-makers (and their beneficiaries).

- Charities should use their knowledge and resources to support and improve the direct relationship a decision-maker has with those with lived experience or those who support a campaign.

- In order for digital campaigning to stay innovative, it’s important to share skills across all areas of an organisation.

- Collaborating with organisations of varying sizes can streamline a digital campaign and thus improve its effectiveness. It’s through collaboration that campaigns turn into movements.

E-campaigning is a powerful vehicle through which those with personal experience can use their voices to achieve social change. However, digital campaigning right now is in a precarious position. The overuse of the same digital campaigning tactics has led to a desensitisation of decision-makers to these methods. But, more than that, they have led to an active mistrust of the charity sector. On top of this, individuals are tired of their experiences being commodified by the very charities trying to represent them. Charities therefore need to reform their digital campaigning practices if they are to mend these layers of broken trust.

This article gives the views of the author not that of Democratic Audit. It draws on the Social Change Agency’s report, which you can read here and the toolkit here.

About the author

Jinan Younis is the Programme Officer at The Social Change Agency. She has led on the JRCT Funded Lost Voices project for the last year, and is the co-author of the Lost Voices Report with Esther Foreman. In her spare time, Jinan is the political editor for online magazine gal-dem, has written a chapter in Virago’s I Call Myself a Feminist (2015) and occasionally writes for national publications.

Jinan Younis is the Programme Officer at The Social Change Agency. She has led on the JRCT Funded Lost Voices project for the last year, and is the co-author of the Lost Voices Report with Esther Foreman. In her spare time, Jinan is the political editor for online magazine gal-dem, has written a chapter in Virago’s I Call Myself a Feminist (2015) and occasionally writes for national publications.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Thank you. This all seems like good advice. But… mass write in campaigns are very blunderbus. They do not really cut through to MOs etc unless they are already sympathetic. In my day it was proforma letters and post cards. They can impact on sheer scale as can emails and petitions. But they do not really engage only act as re-enforcers of more thoughtful and tailored approaches. There is a lot of rebuilding of trust to be done by lobbies of all kinds.