Long read: Public opinion, legitimacy and Tony Blair’s war in Iraq

The Labour Party is still living with the consequences of Tony Blair’s decision to join the US in waging war in Iraq. It destroyed Blair’s credibility and fed the backlash against the ‘moderate’ wing of the party which eventually led to Jeremy Corbyn’s election. In this post, based on his new book, James Strong traces Blair’s attempts to manipulate public opinion in favour of war despite serious doubts about the legitimacy of the invasion. It wasn’t that Blair and his ministers lied about what they believed – it was that they believed things that were wrong, and failed to publicise how weak the evidence was on which their beliefs relied.

A banner outside a Chilcot Inquiry session in 2010, at which Tony Blair was questioned about the Iraq war. Photo: Jason via a CC-BY-NC 2.0 licence

Sir John Chilcot’s statement to the BBC that Tony Blair made the case for war in Iraq “on beliefs, not facts” accords entirely with my findings.

Democracies are not supposed to fight unpopular wars, but Britain did just that in Iraq. Professional politicians are not supposed to court career disaster by ignoring what the public wants. Tony Blair did exactly that when he ordered British forces to help overthrow Saddam Hussein despite hostile opinion polls, critical media commentary and both the largest parliamentary rebellion and the largest street protests against any UK government, ever.

In my new book Public Opinion, Legitimacy and Tony Blair’s War in Iraq (London: Routledge, 2017), I ask how it was possible that Britain wound up fighting a war in Iraq that so many British people considered illegitimate. It’s a complicated question. One consequence that we’re still living with is Jeremy Corbyn’s election as leader of the Labour Party. Corbyn opposed the invasion of Iraq. In fact, as I’ve written about (quite critically) elsewhere, Corbyn opposes the use of force by Western states as a point of principle. His foreign policy stance is only the most obvious way in which he differs from Blair. His style matters too. We know he is far less scripted and far less smooth than Blair. But he is also far more ‘Habermasian’ – in the manner discussed below. He is far more willing to make his case on its merits and far less keen on finding ways to bludgeon opponents into agreeing with him. That, unfortunately for him, is part of why he has struggled to get a fair hearing.

Blair may have taken ‘spin’ to an extreme, but he was right to think he needed to do something to overcome media bias. Corbyn’s struggles are the mirror image of Blair’s – what happens when you spin too little versus when you spin too much. While this post (and the book it highlights) focuses on Blair and Iraq, comparing its findings to Corbyn’s experience underlines the tension between two logics of communication that every political leader has to face.

Public opinion

In the first part of the book, I present what I call a ‘holistic’ account of British public opinion towards the prospect of war in Iraq during the period between January 2002 and March 2003. My holistic approach combines traditional survey methods – opinion polls – with an original content analysis of 2,115 newspaper comment pieces, 333 parliamentary speeches, participant accounts and the treasure trove of detail and documentation released by the Chilcot Report.

A holistic approach better reflects the goals of a foreign policy analysis study. As a foreign policy analyst (FPA), I’m not really interested in what public opinion objectively was. I’m interested in how political elites contested and constructed a certain idea of public opinion, and how that affected decision-making.

It also helps compensate for some of the shortcomings of survey methods. Echoing critical analyses by Herbert Blumer and Pierre Bourdieu, I argue that opinion polls unreasonably assume that every citizen has a prior view on every foreign policy question, that they weight every individual equally when in reality some are more influential than others and that they reflect the concerns of elites with the resources to commission polls. In short, I argue that the latent views of the passive mass matter only when they are likely to be activated across the board – like when a referendum is proposed. Otherwise, I argue it is the active, elite public that really counts.

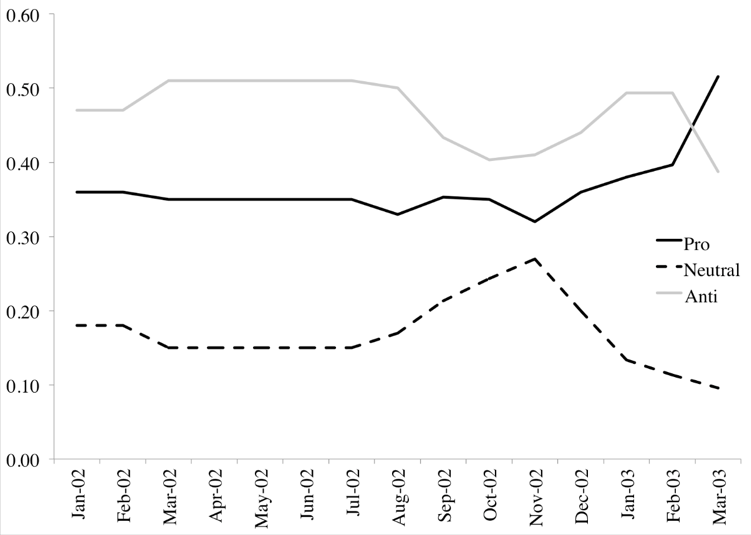

I still use opinion polls – they both reflect and shape elite discourse, and do affect decision-makers too. Figure 1 shows aggregate poll results in the pre-invasion period. It makes clear that for most of the build up to war, most poll respondents opposed the use of force in Iraq.

Figure 1: Aggregate UK opinion poll data on the prospect of British military action in Iraq, January 2002-March 2003. Source: ICM/YouGov.

These results didn’t stop the war for two main reasons. Firstly because, in Douglas Foyle’s classic terms, Tony Blair was an “executor” – he thought public support was desirable, but not necessary. Ultimately, he thought it was his job to lead rather than follow public attitudes. Secondly, and relatedly, because Blair predicted that people would ‘rally round the flag’ if it actually came to war. It is well documented that support for war spikes once the fighting starts. People don’t want to look disloyal, and many resign themselves to the inevitable. Blair was right. In the final week before the invasion support went from 38% to 54%.

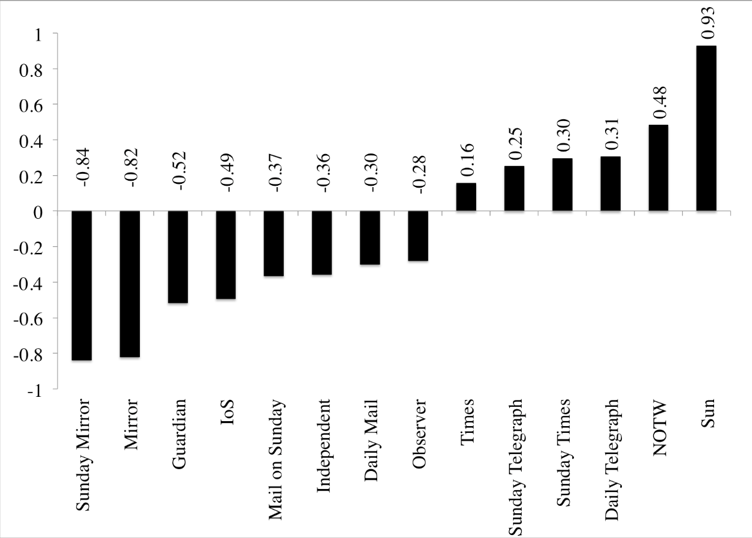

As Figure 2 shows, most British newspapers also predominantly opposed the invasion of Iraq.

Figure 2: Distribution of views expressed in newspaper commentary, by publication.

The picture was not actually as negative as this slide suggests, however. For one thing, it combines editorial lines and the views expressed by commentators. The Observer, for example, printed more anti-war than pro-war commentary, but its editors ultimately broke with their counterparts at its stablemate the Guardian, and supported the invasion. More crucially, the papers that most strongly supported the invasion sold more copies than those that opposed the invasion. During this period the strongly pro-war Sun, for example, sold fifteen times as many copies as the anti-war Independent, nine times as many as the Guardian and 1.7 times as many as the Mirror. On average pro-war publications sold 1.88 million copies and anti-war publications 1.24 million copies. Compounding this advantage still further was that the government’s most vocal supporters were the right-wing publications that traditionally opposed Labour governments, and its main critics were the left-wing publications that traditionally supported Labour.

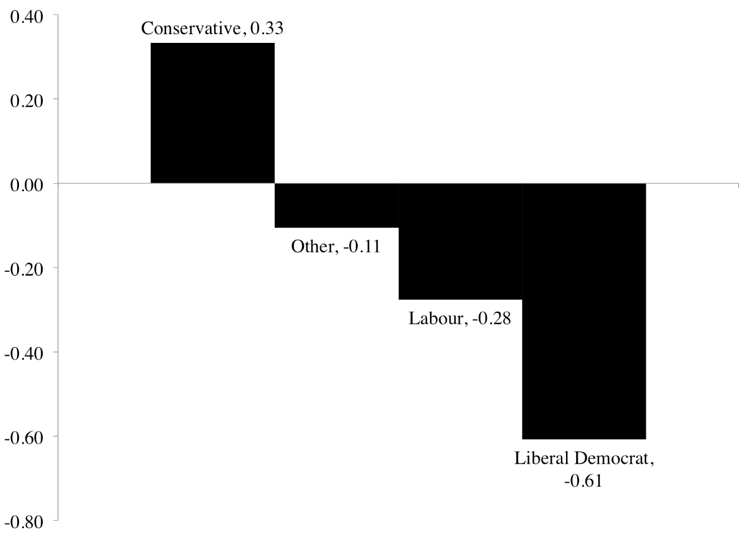

Figure 3: Distribution of net average views expressed in parliamentary speeches, by party.

As Figure 3 shows, finally, the government also enjoyed the support of Conservative Party MPs in the House of Commons, while the small Liberal Democrat party offered the most consistent opposition and the government’s own backbenchers also took a more anti-war than pro-war stance. This meant the government did not need to worry about being punished by voters for ignoring their opposition – it would make no sense to switch from Labour to the Conservatives over Iraq given the Conservatives supported the war. Combined with the massive size of Labour’s 2001 election victory, it also ensured the government could survive back-bench rebellions fairly comfortably. Tony Blair then capitalised on this advantage still further by threatening to resign if MPs voted against him. Forced to choose between their most successful leader ever and Saddam Hussein, many Labour MPs backed Blair.

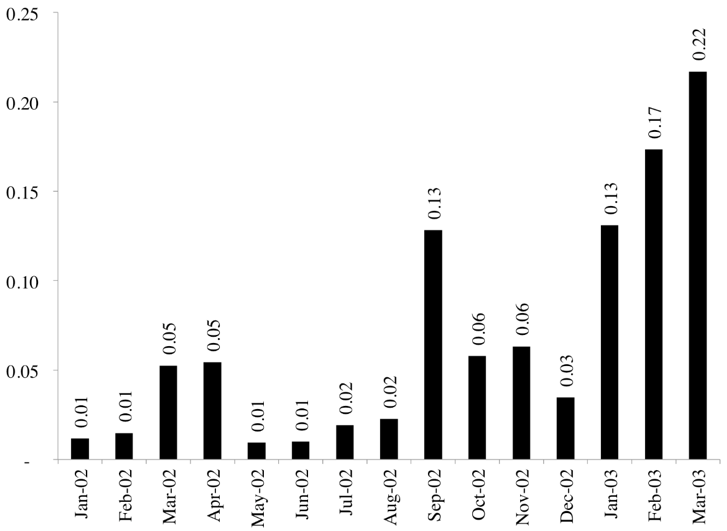

So from an FPA perspective it makes perfect sense that British domestic opposition failed to stop the war in Iraq. A holistic approach also allows us to consider how the direction and the intensity of public attitudes interacted. How much public attitudes matter depends on how much public actors care about the issues at stake. Figure 4 shows what share of the source material investigated during this study came from each month during the pre-invasion period.

Figure 4: Average salience of Iraq war across parliament, press and polls.

As we can see, there were three increasingly significant spikes in public interest, around March and April 2002, September 2002 and then early 2003. The first was driven by President Bush’s condemnation of Iraq as part of an ‘axis of evil’ during his first State of the Union speech in January, and Blair’s subsequent visit to his Texas ranch in April. The second was driven by widespread debate in Washington during August 2002 over the prospect of war in Iraq, by the Blair government’s failure to respond sufficiently quickly to media demands for more information and by the speculation that followed. The third was driven by the UN inspection process, the deployment of troops and ultimately the start of the war.

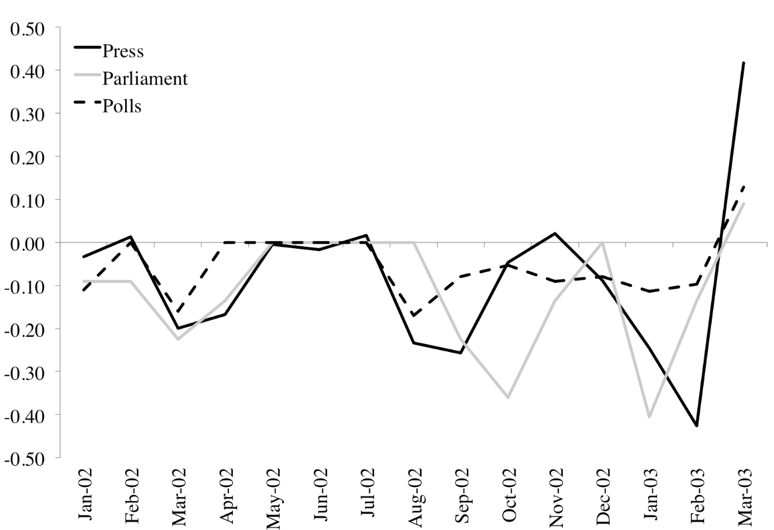

Figure 5: Salience-adjusted average monthly press, parliamentary and poll positions on the prospect of war in Iraq (1= entirely pro-war, -1= entirely anti-war).

Figure 5 combines data on the direction and intensity of attitudes in polls, parliament and the press. It shows spikes in opposition in March 2002, August 2002 and February 2003 followed by a rally effect across all three source types in March 2003. Crucially, what the holistic approach shows is that the first two spikes declined largely because the government released more information that calmed speculation. In April 2002 Blair made clear publicly that he supported confronting Saddam Hussein but that there was no immediate prospect of military action. In September 2002 Bush promised to work through the UN while Blair released the now-notorious ‘dossier’ on Iraqi WMD. In February 2003 Blair successfully blamed France for scuppering the UN process while the inevitability of war bred resignation among opponents.

This observation – that the government’s communications efforts changed few minds but lowered the salience of Iraq as an issue – plays into the discussion of legitimacy.

Legitimacy

Tony Blair tried to argue his way to war in Iraq. He made set-piece speeches, held press conferences and published information dossiers. He took questions from MPs and live television audiences. He led five major House of Commons debates in addition to his weekly question time grilling. He even appeared on MTV. He claimed he wanted a full, open and well-informed public debate on the prospect of war in Iraq, and on the surface he appeared to act that way. Surface appearances can, however, mislead.

Both the content and the form of Blair’s arguments in the pre-invasion period constituted the legitimacy deficit surrounding the war. I define legitimacy as a discursive construct, as a product of public debate. Echoing debates amongst scholars of legitimacy between advocates of political definitions – in which legitimacy derives from public consensus – and normative definitions – in which legitimacy derives from abstract principles, I present two ideal types of communicative legitimacy. At the political end is a model derived from the social theory of Michel Foucault – though I claim no particular expertise in Foucault’s work. From this Foucauldian perspective, legitimacy reflects political consensus and political consensus reflects power. Legitimacy is, in other words, simply a product of power, lacking any distinct normative value. At the normative end, meanwhile, is a model derived from Jurgen Habermas’ Theory of Communicative Action. From this Habermasian perspective, legitimacy derives not just from political consensus, but from a consensus achieved in the right way. For Habermasians, legitimacy emerges from a public debate based on truthfulness, openness to everyone looking to participate, and flexibility on the part of all involved.

The main driver of the legitimacy deficit surrounding the Iraq war was the clash between the Blair government’s explicitly and repeatedly professed commitment to seeking deliberative legitimacy in Habermasian terms, and the much more manipulative, Foucauldian reality of how it actually behaved. Though I find that ministers generally did not lie outright, they were often economical with the truth, especially when discussing the evidence underpinning their beliefs. Though Blair in particular engaged in a range of communication exercises, he still sought actively to control the timing of debates and who participated in them. Even members of the Cabinet found themselves shut out of key discussions, and Blair took certain fateful decisions alone. Finally, though some individuals like Foreign Secretary Jack Straw and (in particular) Attorney General Lord Goldsmith showed some willingness to revisit their views in the face of new evidence, most ministers and officials stuck resolutely to their established positions regardless of developments.

The shortcomings of the government’s communication campaign further undermined its arguments. It claimed that Iraq was developing weapons of mass destruction in violation of UN Security Council disarmament obligations that threatened British national security, that there were good grounds in international law for invading Iraq in March 2003, that overthrowing Saddam was the morally proper thing to do and that the Blair government possessed sufficient political authority to make that decision in the first place. I find each claim problematic – both in terms of Habermasian criteria, and more prosaically in terms of how persuasive they were.

Threat and WMD

By making clear pre-invasion statements about the threat posed by Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction programme, the government both undermined its claim to legitimacy in Habermasian terms and set itself standards it later struggled to meet.

To begin with, the government got key judgements wrong. MI6 failed to spot that one of its sources based his description of Iraqi chemical weapons on the movie The Rock, starring Sean Connery and Nicholas Cage. It was slow to admit as much. More generally, the Joint Intelligence Committee fell victim – admittedly, in line with several allied intelligence communities – to groupthink. Having repeatedly underestimated Iraq’s WMD capacity in the past, the JIC interpreted new intelligence as the tip of the iceberg. It also failed to update its assessments as new information came in – for example, treating the fact that UN inspectors found no banned material as evidence that Iraq was successfully concealing an active WMD programme and not considering the possibility that there was no programme to hide.

More damagingly, ministers drew conclusions that went beyond what the JIC advised. Blair wrote in his foreword to the dossier that Iraq’s WMD posed a “current and serious threat to the UK national interest”. Chilcot concluded that Blair did indeed believe that, but that the JIC did not. Indeed, MI5 advised Blair that Iraq lacked the capacity to threaten Britain directly and that it had showed no sign of intent. Blair similarly wrote that “I believe the assessed intelligence has established beyond doubt” that Iraq was developing WMD. Again, Chilcot concluded that Blair did indeed believe “beyond doubt”, but the JIC thought differently. Jack Straw summed up the issue. He told Chilcot that “all the little bits of information, however patchy and sporadic, all pointed in one direction”. The problem, however, was that – as the JIC advised both Blair and Straw – the information available was indeed “patchy and sporadic”. Indeed, Chilcot found that MI6 had no sources with first-hand knowledge of either Iraq’s capabilities or its intentions during this period. Blair described the evidence as “extensive, detailed and authoritative”. He seems genuinely to have believed it was. It was not, and he was in a position to know it was not.

Finally, the WMD dossier itself conflated the sort of neutral information exercise Blair claimed it represented – the sort of exercise required of a government seeking legitimacy in Habermasian terms – and more Foucauldian policy advocacy. Though Lord Hutton’s inquiry concluded there was nothing intrinsically wrong about the fact that the JIC consulted Alastair Campbell on the wording of the dossier, since the JIC didn’t accept phrasing that didn’t fit the intelligence, there is still a difference between publishing intelligence assessments – which are usually balanced, nuanced and uncertain – and publishing the dossier, which was clearly designed to make the case for war. One particular element that later proved controversial was the claim that Iraq could deploy chemical and biological weapons within 45 minutes of an order to do so. Journalists interpreted this as a claim that Iraq could attack Britain in that sort of timeframe. But the JIC’s assessment referred specifically to battlefield weapons, which don’t have that kind of range.

The government, in other words, was neither entirely truthful in presenting its case to the public, nor flexible in the face of contradictory information. It wasn’t that ministers lied about what they believed – it was that they believed things that were wrong, and failed to publicise how weak the evidence was on which their beliefs relied. To some extent, this worked. Though critics challenged the dossier, and it changed few minds – polls suggested just 4% of respondents shifted stance after the dossier came out, mostly anti-war to undecided – it did dampen damaging speculating over the summer of 2002. At the same time, however, the dossier established unrealistic criteria. Had the government said “we don’t really know what’s going on in Iraq, but it doesn’t look good” it would not necessarily have looked dishonest later on. But it would probably have faced much stronger opposition.

International law

An independent commission famously described NATO’s intervention in Kosovo as “illegal, but legitimate”. Britain’s UN Ambassador Jeremy Greenstock later described the Iraq war as “legal, but of questionable legitimacy”. Chilcot refused to comment on the substantive question of whether or not the invasion of Iraq was in fact legal, but described the process by which ministers took legal advice as “far from satisfactory”. As Philippe Sands QC, a leading international lawyer, put it – “far from satisfactory” is “a career-ending phrase” in civil service language.

Part of the problem lay in the “deliberate ambiguities…necessary to get a consensus” on UN Security Council Resolution 1441 – as British ambassador to the US Christopher Meyer put it. Part of it lay also in Blair’s refusal to involve Attorney General Lord Goldsmith in negotiations surrounding the resolution, fearing either that involving him would lead to leaks, or that he would set legal standards impossible to reconcile with the political realities. As a result, Chilcot concluded that the British government voted for SCR 1441 despite the fact it “didn’t really know what it was voting for”. It took Straw and Blair until a week before the invasion to agree an interpretation. Blair clearly believed Iraq would quickly be caught refusing to co-operate with UN weapons inspectors. When that did not happen, he had to disparage an inspection process he worked hard to establish, and then search for ‘smoking guns’ he knew were unlikely to be found.

More damaging still was the fact that Blair believed both that Britain should uphold international law and that it was morally proper for powerful states to use force to overthrow regimes, like that in Iraq, that abused their own people. Blair believed in regime change, and he believed his own moral judgement was superior to that of those who criticised him – even the Pope himself. He never acknowledged, let alone resolved, the clash between what international law actually allowed and what he personally believed it should allow. That meant he had to downplay his strong commitment to regime change because it clashed with his equally strong commitment to acting within the law. This led to contradictions – he railed against the injustice of leaving Saddam Hussein in power and promised to do just that if Saddam complied with UN inspections. He described his “enthusiasm” for regime change and called it a “myth” that he sought it in Iraq. Blair was not truthful, in that he downplayed how strongly he believed in regime change, and failed to discuss the clash between his legal and moral positions. He was not open, in that he tried to exclude the Attorney General from policy discussions. He was not flexible, given he repeatedly rejected legal advice that did not match what he felt he could negotiate in Washington and New York, and ignored moral counsel that contradicted what he personally thought. No wonder his Chief of Staff Jonathan Powell accused him of having a “messiah complex”.

Freedom Fries

he claim that France prevented agreement on a ‘second’ UN Security Council Resolution failed all three Habermasian criteria but, interestingly, did not lead to punishment after the invasion. It was a rare example of how normative and political legitimacy can play out differently.

Then International Development Secretary Clare Short later described this claim as “one of the big deceits” of the entire pre-war period. As Ambassador Greenstock told Chilcot, Britain never secured the minimum nine votes needed to pass the ‘second’ resolution – so France’s threat to veto it was not decisive. As Blair told Bush in a private letter on 11 March 2003, however, French President Chirac’s clear determination to take a stand did “provide some cover” for Britain’s failure at the UN. Ministers and officials actively blamed France and encouraged press and parliamentary critics who echoed that blame. They continued despite frantic French efforts to clarify Chirac’s 9 March statement that “whatever the circumstances, France will vote no”. When French Foreign Minister Dominique de Villepin told Jack Straw that Chirac was still open to compromise, Straw ignored him and insisted that he “read the comments differently” – as if his interpretation of French foreign policy carried more weight than that of the French foreign minister. British ambassador to Paris Sir John Holmes wrote to London that “our position can hardly surprise the French, nor the fact that we are using Chirac’s words against him…he did say them, even if he may not have meant to express quite what we have chosen to interpret”.

No one in Britain suggested taking France’s position – that military action might yet be necessary, but that it was not justified yet – seriously. That betrayed a lack of flexibility. Ministers maintained that France had closed off all room for compromise, despite French officials insisting the contrary. That reflected a lack of truthfulness. Finally, the government tolerated suggestions – mostly from public commentators – that France did not really deserve to have a say – that its objections were unwarranted in some way. Blair’s insistence that he could legitimately ignore an “unreasonable” veto at the Security Council underpinned this stance. This showed a lack of openness. Despite these shortcomings, the argument worked. YouGov found 70% of British voters rejected Chirac’s stance. Labour MP and Chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee Donald Anderson attacked France. A series of Sun editorials compared Chirac to “a cheap tart” and a “worm”, contrasting his “arrogance and greed” with Blair’s “highest moral principles”.

Conclusions

On 28 July 2002 Blair wrote to Bush “I will be with you, whatever”. Cabinet neither discussed nor even knew about this letter. In public, Blair maintained “no decisions have been taken”. At the end of October he formally offered British ground troops to the US for planning purposes. In mid-January 2003 he privately gave up on the UN inspection process and approved invasion plans. Again, Cabinet was not told. It is true that the government faced widespread and at times unreasonable press hostility. It is true that some Cabinet ministers leaked everything they heard about Iraq to the press at the earliest opportunity. It is true that some parts of the government’s argument could not have survived a full, frank, open and flexible public debate.

But the Blair government, and Tony Blair in particular, repeatedly claimed they sought a proper public deliberation. In making that claim, then failing so dramatically to meet it, they created the conditions for the legitimacy deficit that followed. At the same time they made inconsistent, irreconcilable and incorrect arguments that became impossible criteria for success.

That the Stop the War movement failed to stop the war made a good deal of sense. That the invasion nevertheless wound up widely regarded as illegitimate made sense, too. Ultimately the approach the government took proved neither properly deliberative nor persuasive.

What we learn from all this is simple. How governments talk about foreign policy matters. It influences public debate, though more by raising and lowering the salience of an issue than by persuading people to adopt a different view. It determines both the political and the normative legitimacy of a decision. It establishes criteria for success. The clash between deliberation and persuasion in the Blair government’s case for war in Iraq explains a good part of the legitimacy deficit surrounding it. Shortcomings in the specific arguments made explain the bulk of the rest. It would perhaps have been better not to have talked so much after all.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It is adapted from the original here. A podcast of the launch event from which this text is drawn – featuring comments from Professor Sir Lawrence Freedman of King’s College London and Professor Juliet Kaarbo of the University of Edinburgh – is available here. The book is available to read online for free, for a limited period only.

James Strong (@dr_james_strong) is Fellow in Foreign Policy Analysis in the Department of International Relations at LSE.

James Strong (@dr_james_strong) is Fellow in Foreign Policy Analysis in the Department of International Relations at LSE.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.