Three key lessons from Labour’s campaign – and how the party needs to change

Jeremy Corbyn has confounded his critics and increased Labour’s share of the vote in the General Election. But the party is some way from being able to command a parliamentary majority, says Patrick Diamond. Labour has articulated a vision of society which appeals to many young people and ‘left behind’ voters. Now the party needs to get over the intellectual defensiveness which has afflicted it for decades – and reach out to people in English constituencies who have no tribal loyalty to Labour.

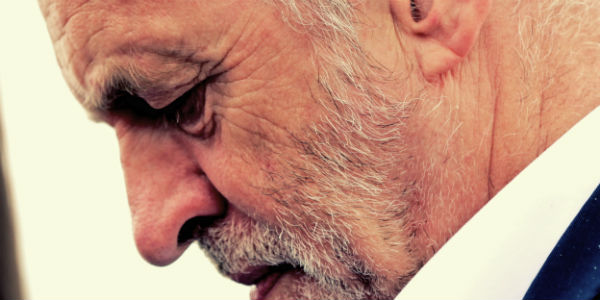

Jeremy Corbyn on the campaign trial in West Kirby. Photo: Andy Miah via a CC-BY-NC 2.0 licence

Politics in the Labour party will never be the same again in the aftermath of the 2017 general election. Only six weeks ago many commentators, most Labour MPs, party members and even Jeremy Corbyn’s allies feared he would be humiliated at the ballot box.

It didn’t happen. Labour fought an insurgent campaign in which Corbyn deftly exploited his status as the underdog; the Labour party appears to have excited young people as well as so-called ‘left behind’ voters in ways not seen for decades. Criticisms of Corbyn’s leadership style focused on his inept approach to internal party management and estrangement from his own parliamentary party; where Corbyn exceeded expectations was his ability to fashion a distinctive, eye-catching political agenda that captured the imagination of the electorate, and distanced the Labour party from its potentially ‘toxic’ legacy (one of the historian Stuart Ball’s key criteria for effective opposition party leadership).

Of course, it has not been plain sailing for Corbyn’s Labour. Arguably, the leader’s greatest vulnerability has been his reluctance to acknowledge the place of other traditions in the Labour party beyond his own heterodox brand of socialism. Corbyn’s weakest moments during the campaign were his defensiveness over the nuclear deterrent, as well as controversy over his previous reluctance to condemn IRA terrorism. There are still major questions about the viability of Labour’s manifesto, for all that its ideological clarity inspired the faithful. Still, there can be little doubt that the campaign Corbyn fought marks a decisive shift in the politics of the Labour party to which all sections of the party will now be obliged to respond.

So what strategic lessons can, and should, we glean from the Corbyn leadership project in the wake of the general election result?

The first lesson is that Corbyn’s politics evidently appeal to many younger voters, as well as the social groups that have increasingly abstained from voting in the UK since the late 1980s. The dynamic here was that Corbyn projected ‘hope’ because his programme was not constrained by conventional electoral calculation; Labour’s prospectus offered a different vision of society after nearly a decade of spending cuts, tax rises, and missed deficit reduction targets. Corbyn’s views on policy articulated a rare combination of clarity and conviction. The Labour leader offers an innovative politics of participation which is about doing things ‘with’ people rather than ‘to’ them, sweeping away anachronistic institutions and inherited privilege; if carried forward this might be the platform for a resurgence of British social democracy.

The challenge ahead for Corbyn’s project will be to construct the electoral alliance between the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ that is required to win greater numbers of marginal seats, enter government, and deliver policies like progressive redistribution and public investment. Another general election appears likely to be called relatively soon. A Labour victory will mean winning in English constituencies like Reading West or Thurrock that Labour was unable to carry last Thursday.

The second lesson of the Corbyn leadership project is that Labour needs to get over the intellectual defensiveness that has plagued the party since the late 1980s. Corbyn says he now wants an open debate about policy; he ought to be taken at taken at his word. In the past, some modernisers behaved as if the best approach to making Labour a party of government was to give the entire PLP and party membership an intellectual lobotomy. This risked denuding the Labour party of the capacity to think and revitalise itself. The ascendency of Thatcherism convinced many that Britain had become an inherently conservative country, and that the Left could only win by accepting the basic parameters of the Thatcher settlement. In this election under Corbyn, Labour made its most audacious attempt since 1945 to shift the centre ground of politics towards the Left.

The Corbyn leadership project’s third lesson is that when effectively presented, measures that are widely perceived to be traditionally ‘left-wing’ are still popular with mainstream voters. Among the most important issues raised in the Labour manifesto was the question of public ownership in a post-industrial economy geared towards the production of information and knowledge. For the last 30 years, the assumption in the Labour party has been that whether ownership is public or private no longer matters. It was thought that utilities and public services delivered through the private sector could still be regulated effectively in the public interest. Nationalisation in the 1990s was rejected by Labour because it was believed to be too costly to bring major public utilities like water, gas or rail back into public ownership. Yet it is clear that since 1997, public opinion has become more hostile towards private ownership of the utilities, especially rail. Previous assumptions ought to be interrogated: many privatised industries in the UK are natural monopolies; the privatisations of the 1980s and 1990s have been detrimental both to consumer welfare and economic efficiency.

None of this ignores the fact that Labour is still some way from winning a parliamentary majority at a general election. The party has made significant progress since 2015; but to defeat the Conservatives Labour has to be capable of winning seats throughout Britain. It is not enough merely to rouse already committed supporters: the party has to be capable of reaching out to ‘non-Labour Britain’ where there is little tribal affiliation with the Labour party. It is clear from the election campaign and the terrorist atrocities in Manchester and London that national security is likely to remain a major issue in British politics. Offering voters social justice without addressing their basic concerns about physical insecurity in a world of borderless crime and terrorist threats is a recipe for future defeat. To help the most vulnerable and marginalised in Britain, Labour has to be a party of power rather than a pressure group of social protest.

Corbyn has spectacularly demolished Theresa May’s hopes of securing a decisive Tory majority. The ‘moderates’ in the Labour party will have made a grave error if they dismiss Corbyn’s approach to strategy and policy as outdated and destined to end in failure. Yet it remains doubtful as to whether as things stand Corbyn has an electoral or governing project that can end the latest phase of Conservative hegemony in British politics. That is the next crucial task of revitalisation for the British centre-left.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

Patrick Diamond is University Lecturer in Public Policy at Queen Mary, University of London.

Patrick Diamond is University Lecturer in Public Policy at Queen Mary, University of London.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Originally posted by Democratic Audit UK 12/06/2017 […]

“This post represents the views of the author – not those of Democratic Audit UK.” Well that’s clear, but I’m not sure what this piece has to do with Democracy. Surely there can be no argument for thinking our first past the post system is actually democratic, where one party runs the country on a minority of our votes. Yet the whole of this article is based on Labour somehow getting into power on that basis.

…”an innovative politics of participation which is about doing things ‘with’ people rather than ‘to’ them”. Here’s a chance to discuss democracy. If, in a democratic system, every vote counted equally, everyone had an equal say as to how the country is run, then we the people would be able to participate and policies would develop to respond to all our diverse views.

There are loads of opinions going round about what Labour should do next – but Democratic Audit could be a bit more choosey.