No one won this General Election – and Labour’s internal wrangles are far from over

No party emerges with much credit from the general election, writes Robin Pettitt. Theresa May is diminished and she may not survive for long, even with the support of the DUP. Jeremy Corbyn captured 29 more seats but still lost the election, and his personal standing with voters remains poor and his problems with the parliamentary Labour party are unlikely to go away. The Lib Dems’ desire for a second referendum, meanwhile, has not chimed with the public.

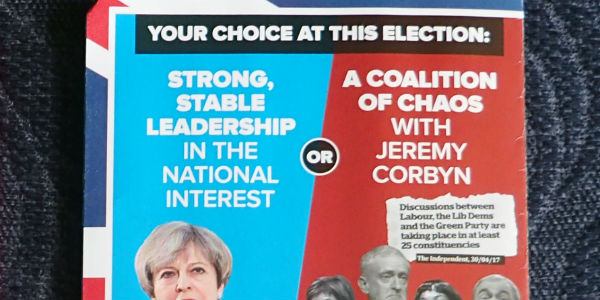

Detail from a Conservative election leaflet. Photo: Gwydion M Williams via a CC BY 2.0 licence

Theresa May’s gamble in calling an early election – like Cameron’s Brexit gamble – has misfired spectacularly. Considering that the Conservative campaign, at least at first, was heavily focussed on May The Leader (‘Theresa May’s team’) and that the Conservative party is ruthless in dealing with leaders who fail to win, May’s tenure at Number 10 is likely to come to a messy end in the not too distant future. Having thrown away a double-digit poll lead during a campaign that was based on May’s ability to provide ‘strong and stable’ leadership, the blame will be laid squarely at May’s door, and the life expectancy of her leadership has been drastically cut.

May’s ‘coalition of chaos’ is looking like it may indeed come to be – albeit not quite the way she meant it. Whether May forms a coalition with the Democratic Unionist Party or brokers a more informal arrangement, it is unlikely to be anything approaching ‘strong and stable’.

Jeremy Corbyn has yet again proven his detractors wrong, winning 29 more seats than Ed Miliband managed in 2015. What this means for the long term future of Corbyn’s leadership and the future trajectory of the Labour party is incredibly difficult to predict. The fact remains that while Labour under Corbyn has not suffered the catastrophic defeat feared by many in the parliamentary party, his personal standing with voters remained unimpressive. Yes, the negative views of his potential as a Prime Minister did lessen, but even at the end of the campaign May still outdid Corbyn. In the long term, it is likely that this result will be seen as being down to May’s failures, rather than Corbyn’s successes.

What changed during the campaign was not Corbyn – who has arguably not changed that much in political terms for decades. His consistency, innate honesty and earnestness seem to have become a strength, but his personal views are still not that popular with many voters. Rather, what changed drastically was May’s image as a strong and consistent leader. Repeated u-turns contrasted badly with the ‘strong and stable’ slogan. So while Corbyn has certainly proven himself an assured and convincing campaigner, his perceived suitability for the role as Prime Minister is still very much in doubt. This will probably in due course return as a problem for his leadership and for the future of the Labour party.

The Liberal Democrats, meanwhile, have not been able to draw on anti-Brexit sentiment to the extent they hoped. It seems that many Remainers have generally accepted Brexit, but were not happy about May’s hard version of it. The party will probably have to take a hard look at their stance on Brexit. This result seems to have been a rejection of one version of Brexit – rather than a rejection of Brexit as a whole, as the Liberal Democrats were advocating through their backing for a second referendum.

Finally, as May never tired of reminding us, the Brexit negotiations are due to begin in 10 days’ time. It looks very unlikely that the next UK government is going to go to Brussels with a strong mandate for any particular version of Brexit. This will only serve to make an already profoundly complicated process even more difficult. On a personal note, I will probably hold off on updating my British politics teaching materials for a while longer.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

Robin Pettitt (@RobinPettitt) is a Senior Lecturer in Comparative Politics at Kingston University. Also by this author:

No ‘suicide note’: Jeremy Corbyn, not his manifesto, is what holds Labour back

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

This is a quick morning-after response to GE17 from a serious academic. I personally don’t know how to make an academic response – so it would seem natural that responses today will tend to be just opinions – albeit educated.

Here are some opinions:

“Theresa May’s gamble in calling an early election.” No I don’t think she thought it was a gamble – she thought it was a fore-gone conclusion, that’s why she went for it. ( I don’t think she does gambles.)

“while Labour under Corbyn has not suffered the catastrophic defeat…, his personal standing with voters remained unimpressive.” Well maybe for those readers of the Daily Mail, Sun etc., but one of the surprises of this election is how Jeremy Corbyn withstood that onslaught of negativity, presented a clear strong vision, engaged in debates and did not resort to personal mud-slinging – in so doing demonstrated to very many voters strong leadership qualities.

“His perceived suitability for the role as Prime Minister is still very much in doubt”. Again whose perception? All leaders will have some detractors.

“This will probably in due course return as a problem for his leadership and for the future of the Labour party.” This opinion may be educated but I would expect the opposite: he’ll be getting much more respect within Labour as from today.

While Labour is not my first choice party, I’m impressed with their achievement. Opinion.