Party canvassers don’t change people’s opinions, but they do persuade them to vote

Party volunteers up and down the country (and especially in marginal seats) are pounding the streets campaigning on their party’s behalf. But what sort of effect, if any, do they really have? Charles Pattie, Ron Johnston and Todd Hartman show that while doorstep campaigning is unlikely to change people’s political opinions, it is particularly effective at persuading a party’s existing supporters to turn out to vote – especially if they are Lib Dems.

Lib Dems on the streets in Haringey, north London. Photo: Haringey Liberal Democrats via a CC-BY-ND 2.0 licence

National campaigns, organised from party HQs, are always vital at general elections. Such campaigns are changing, too; 2017 may yet prove to be the campaign when social media begins to achieve major cut-through as a vehicle for electioneering (the Conservatives, for instance, have used digital platforms such as Facebook to disseminate advertising attacking their opponents)..

But spare a thought for the parties’ local volunteers and members. Largely unsung, they spend the election campaign (and much time before then, too) putting up signs and posters in front gardens and windows, delivering election leaflets, canvassing voters, staffing high street campaign stalls, all in an effort to help their candidate to victory. In total, a substantial amount of time, effort and money (around £22.6 million in 2015, most of it raised locally) is expended on candidates’ constituency campaigns.

Does all this local campaign effort make any tangible difference to the election results? A large body of evidence shows the major parties focus their greatest constituency campaign efforts on their most marginal contests, the constituencies where a few votes either way might change the result. And it pays off. Other things being equal, the harder parties campaign in a constituency, the better they do there, and the worse their rivals do. Parties ignore their local battles at their peril.

That said, when one party is well ahead of its rivals in the national vote competition, constituency campaign efforts might affect the eventual size, but not the fact, of the winner’s parliamentary majority.

But if (as seems to be the case) constituency campaigns do affect party performance locally, how do they do so?

One way in which they might is by changing voters’ political opinions. A common (though not very accurate) view of party canvassing is that activists try to persuade sceptical voters to change their minds and accept the canvasser’s party’s position and policies. We might refer to this as the ‘persuasion hypothesis’.

An alternative, and somewhat different, means by which constituency campaigns might affect the results of elections is by encouraging as many as possible of those already predisposed to the canvassing party to actually turn out and vote for it (call it the ‘mobilisation hypothesis’).

To examine the evidence for these hypotheses, we turn to the 2015 British Election Study Internet Panel, a large survey of British voters which interviewed the same individuals on several occasions between February 2014 and May 2015, the latter just after the general election. Crucially for our purposes, they were asked, on several occasions, about their political opinions, their voting intentions before the election, how they actually voted, and, most importantly, whether they had been contacted by any of the major parties. This lets us examine whether those who were contacted by a party were more likely to change their political views than those who were not contacted (persuasion) or to turn out and vote for the party (mobilisation). We focus on what people reported in February 2014 and immediately after the election in May 2016.

Fifty-nine percent of survey respondents did report some contact from the parties during the 2015 campaign: 40% were contacted by the Conservatives, 45% by Labour and 27% by the Liberal Democrats. Leaflets were by far the most common form of contact, received by over 90% of those reached by each of the three parties. Home visits during the election campaign (the traditional vehicle for party canvassing) were reported by 16% of those contacted by the Conservatives, 22% of those contacted by Labour, and 12% of those contacted by the Liberal Democrats. Around one in five of those contacted by Labour and the Conservatives, and 15% of those contacted by the Liberal Democrats said they had been emailed. No other form of contact was reported by more than 10% of those contacted.

This hardly supports the ‘ideal’ image of in-depth doorstep conversations between party volunteers and voters. Election leaflets are poor substitutes, and many will have gone rapidly from voters’ doormats to their bins having been read (if at all) only deeply enough to note which party had delivered the leaflet; and emails may go into the trash bin without careful reading. How voters reported experiencing the local campaign in 2015, therefore, does not sound conducive to strong ‘persuasion’ effects: who, realistically, is liable to change their political outlook based on (cursorily examined) election leaflets?

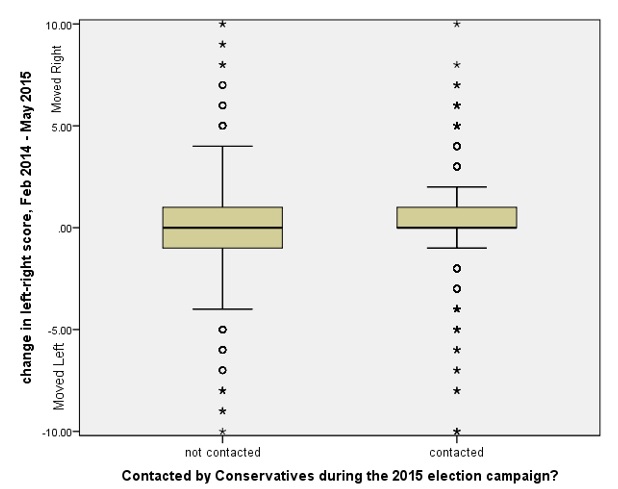

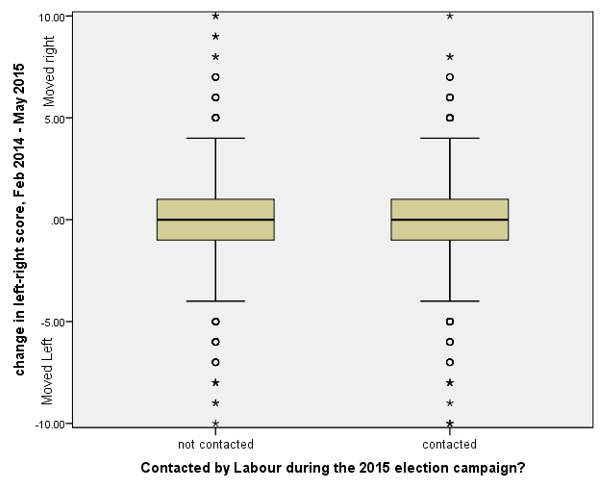

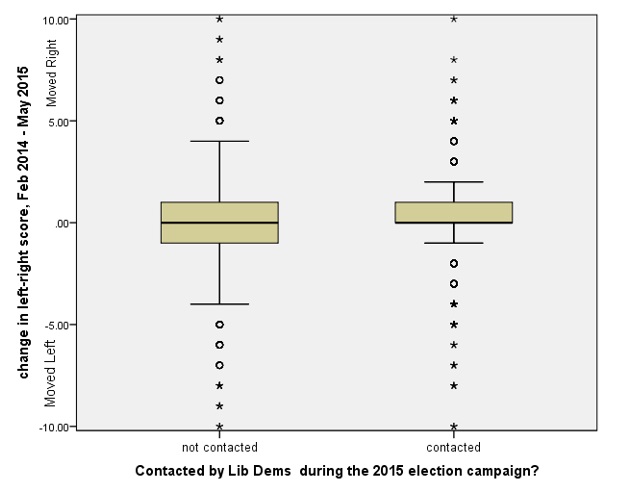

But we should not dismiss the possibility out of hand. What does the evidence say? The British Election Study asked respondents, in both February 2014 and May 2015, to place themselves on a left-right political scale (with 0 indicating the most left-wing position possible, 10, the most right-wing). Because the same people answered the question on both occasions, we can see just how much (or how little) their position on this basic political dimension shifted over the course of the year. Subtracting each individual’s left-right score in February 2014 from their score in May 2015 gives us a scale which runs from a minimum of -10 to a maximum of +10. Individuals who put themselves in the same location on the left-right scale on both occasions will have a score of 0; those who moved to the right over the period will have a positive score (and the more positive, the larger the move to the right); those who moved to the left will have a negative score (again, the more negative the further to the left they will have moved).

As the left-right dimension is one of the basic political divides in British politics, most people have relatively clear views of where they stand. Very few individuals changed their minds much between February 2014 and March 2015: 81% of individuals moved no more than one point right or left on the scale between the two dates – and given the imprecision of the scale (while most of us will have a good sense of roughly where on the scale we might sit, not even the most politically aware among us are likely to know of exactly which number on it best captures our view) this could well be simple random measurement error.

That said, some individuals moved rather further on the scale (and a very few claimed to have moved all the way from far left to far right, or vice versa). So were those contacted by the parties during the election campaign more likely to shift their ideological position (and in the direction of the party by which they were contacted) than those who were not contacted?

The answer is a clear ‘no’! As the following graphs show, whether people were contacted had no influence on whether, how far, or in which direction people shifted their left-right positions. The graphs show the median change in ideological position (the thick black line in each box), the inter-quartile range (the top and bottom of each box: the middle 50% of individuals lie inside this box) and the maximum and minimum changes. The fact that the median for those contacted by the party (on the right of the figure) is almost identical to that of those not contacted by it (on the left) shows that party contact did not have a distinctive effect on whether people shifted their position on the left-right scale. (We have also looked at whether being contacted by the Liberal Democrats, the centre party in UK politics, moved people way from either extreme on the left-right scale and into the centre: it did not).

So much for the ‘persuasion’ hypothesis. Whatever local campaigners were doing, they were not changing most people’s political opinions.

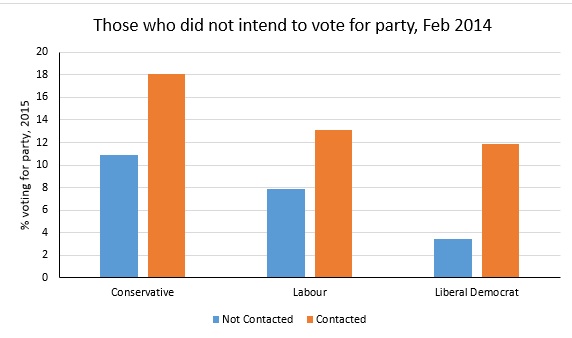

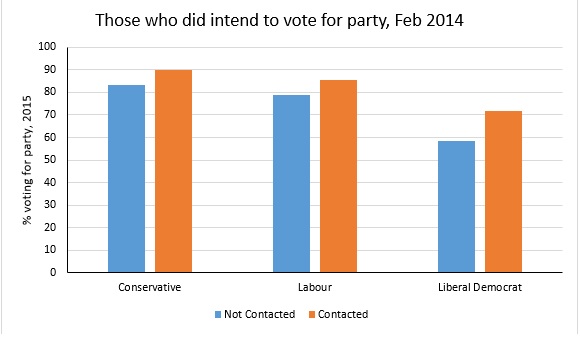

What about the mobilisation hypothesis? Did being contacted by a party make people more likely to turn out and vote for it? We look at this by comparing how people said they intended to vote when asked in February 2014 with how they actually voted in 2015. For each party, we look at two groups of voters: those who said they did not intend to vote for a party when asked at the start of 2014; and those who said they would vote for the party when asked in 2014. We then look at the percentage who went on to vote for the party in 2015. Were those contacted by a party during the 2015 election campaign more likely to be either joiners or loyalists than those not contacted?

The first graph looks at those who did not plan to vote for a party in February 2014. As this group contains not just people who might consider voting for the party but also people who would never do so, it is hardly surprising that only relatively low percentages went on to vote for each party in 2015. Only 8% of those who did not originally intend to vote Labour and who were not contacted by Labour during the election went on to vote for the party in 2015. But regardless of the party, those contacted were more likely (by between 5 and 8 percentage points) to switch and vote for it than were those who were not.

And, as the next graph shows, being contacted by a party’s campaign made those who had originally planned to vote for it more likely to stay loyal to it. Among this group, unsurprisingly, higher percentages went on to vote for the party across the board than was the case for our previous group of ‘joiners’. After all, these voters were already leaning towards the party in question. But, once again, those contacted by the party they originally intended to vote for were noticeably more likely to go on and do so in 2015 than were those not contacted (by between 6 and 13 percentage points – the largest ‘boost’ was for the Liberal Democrats).

Even though the local campaign is primarily experienced through ephemeral leaflets and fleeting contacts which have little or no effect on voters’ opinions and political views, they do mobilise support. Ask (by contacting voters), and you’re more likely to get.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

Charles Pattie (left/above) is a Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Sheffield.

Charles Pattie (left/above) is a Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Sheffield.

Ron Johnston is a Professor in the School of Geographical Sciences at the University of Bristol.

Todd Hartman is a Lecturer in Quantitative Methods at the University of Sheffield.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Informations here: democraticaudit.com/2017/05/31/party-canvassers-dont-change-peoples-opinions-but-they-do-persuade-them-to-vote/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More: democraticaudit.com/2017/05/31/party-canvassers-dont-change-peoples-opinions-but-they-do-persuade-them-to-vote/ […]

[…] – A British study finds that party canvassers are more effective at raising turnout than changing minds. [Democratic Audit] […]

[…] – A British study finds that party canvassers are more effective at raising turnout than changing minds. [Democratic Audit] […]

[…] – A British study finds that party canvassers are more effective at raising turnout than changing minds. [Democratic Audit] […]

[…] – A British study finds that party canvassers are more effective at raising turnout than changing minds. [Democratic Audit] […]

[…] – A British study finds that party canvassers are more effective at raising turnout than changing minds. [Democratic Audit] […]

[…] – A British study finds that party canvassers are more effective at raising turnout than changing minds. [Democratic Audit] […]

[…] – A British study finds that party canvassers are more effective at raising turnout than changing minds. [Democratic Audit] […]

[…] – A British study finds that party canvassers are more effective at raising turnout than changing minds. [Democratic Audit] […]

To describe 22 million pounds reverentially as a ‘substantial amount of money’ in an election in a country like the UK in the modern era is to effectively deal in a past era of electioneering. It is less than the value given in just one day of what amounts to advertising by the major tv networks dressed up as ‘election coverage’ to the main parties. We’ll be hearing shouts of ‘Bring Back the 14 Day Rule’ next…

These tiny resources spread across 650 constituencies explain why some tired hand-delivered 1950s-style leaflet from the parties (‘how drab in comparison with the carpet shop’s nice little brochure’) is now about the only contact that local parties have with their constituents. You can’t even mail a communication to all voters outside of the Royal Mail one, which is censored by the state, without busting the allowed budget.

The reality is that people do NOT see actual people, they see something shoved through the door and they don’t even know whether it’s the Royal Mail thing or something else.

When I stood for London Mayor in 2000 I was told I would be disqualified if I actually wrote to even 20% of my constituents or spent enough cash to get to them (candidates ‘in the wrong class’ having been barred from tv access by state radio and tv). By 2008 as a prospective candidate again, even though I was an elected member of the London Assembly, I was told that the state rules designed to suppress political diversity by the BBC in collusion with the main parties upon whom they depend for their privileged position had become even more onerous and cleverly designed.

Is it any wonder that UKIP after that fiasco, clearly loaded against new challengers by the elite, put all their efforts into alternative media and an online presence. And it really should be no surprise that it is only via the ability to get the message across through media that were not biased or opposed to alternative voices or controlled by the state did the party suddenly in the second decade of the 21st century make advances to those natural supporters to whom it had been invisible through the twin attack of denial of media coverage and a ban on spending money to get in touch with constituents any other way. “Compare and contrast UKIP’s position between the two elections of 2010 and 2015″…

Set against this, a tiny % of the population trudging around with a few leaflets spending a few ha’pennies in each constituency appears to the Loser’s Guide to 21st Century electioneering.

[…] Source […]